Documentary director Steve James ("Hoop Dreams") and a banking court case might seem to be an unlikely match, but prepare to be pleasantly — and provocatively — surprised by "Abacus: Small Enough to Jail," which opens in New York City on Friday and then rolls out to other parts of the country.

Abacus, a family-owned bank in New York City’s Chinatown, was the only U.S. bank to be indicted in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. James smelled a good David-and-Goliath story here, and he's found one. The director manages to weave a dramatic, narrative thread around the Sung family’s struggle to defend itself as a pawn in the fiscal firestorm against Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance and an American legacy of anti-Chinese racism.

"Abacus" achieves depth because it's about so much more than a court case, a family or the mortgage crisis: it’s a unique portrait of how an iconic community, New York City’s Chinatown, is a nation unto itself, with its own rules and traditions, which has persisted, sometimes successfully and yet with significant costs.

[salon_video id="14769464"]James has himself been famously subjected to a career-long miscarriage of justice — of the tinsel-tinged variety — having been repeatedly overlooked by the Academy Awards. But with "Abacus," the Oscar verdict may finally be in his favor.

Salon recently sat down with him to talk about the film, the Sungs, the financial crisis and more.

How did you come to make the film?

One of the producers, Mark Mitten, has been friends with the Sung family for over 10 years. He first approached me about the story right before the trial. We were both struck by the fact that no one in the mainstream media was really covering this case. The only substantive thing written at that time was by Matt Taibbi in the introduction to his book "The Divide." He wrote about the indictment of Abacus as an example of the unequal application of justice. Mark and I felt this story was very important, precisely because it wasn't being told.

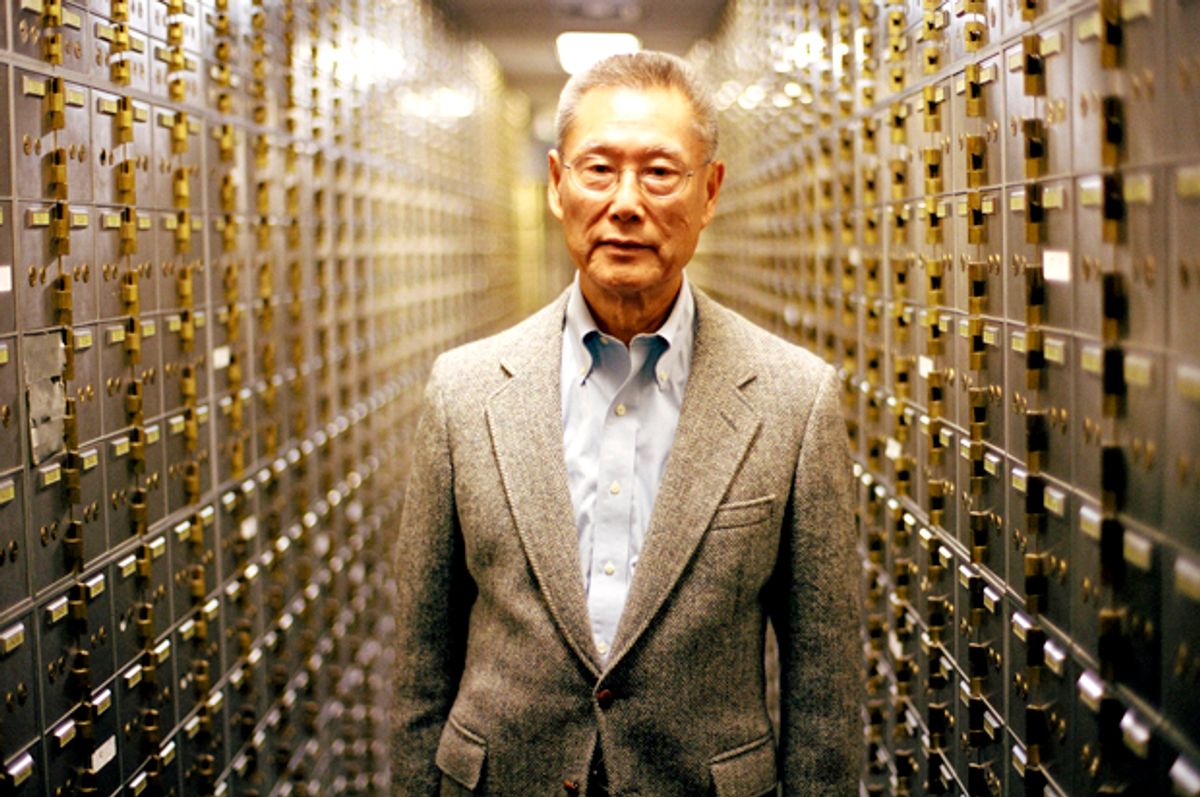

Describe the process by which you came to the film's clear position [Thomas Sung, the Abacus patriarch, is compared to Jimmy Stewart’s character in "It’s a Wonderful Life"] that the Sung family was the subject of a miscarriage of justice.

I think Matt Taibbi’s piece predisposed me to think this was a miscarriage of justice. But it wasn’t until I met the Sungs and filmed with them for several days that it became clear to me that this case made little sense. The Jimmy Stewart reference came from people in the community, which speaks to the high regard that they have for Mr. Sung.

Abacus was the mirror opposite of the Big Banks in every respect. And this trial had nothing to do with the mortgage crisis of 2008 in terms of the fraud. But it had everything to do with it in terms of the DA’s office framing of the indictment and trial.

Are you convinced that they are 100 percent innocent of having committed any crime during the years that led up to the fiscal crisis? What about crossing an ethical boundary? Or . . . negligence?

Am I 100 percent convinced that the Sungs are innocent of what they were charged with? Yes, absolutely. I do not believe they at all condoned or encouraged fraud. If they had, they would never have fired Ken Yu, reported him, then initiated their own internal investigation that resulted in the firing of several other loan officers. They never would have sent the aggrieved borrower to the police! Did they need better oversight? In retrospect, yes. I think the Sungs would agree. But was the fraud going on at Abacus unusual? No.

I think its easy for people to forget that most of the fraud that was happening at Abacus (with the exception of Ken Yu) was of the type of fraud that went on everywhere before the 2008 crash. I myself used a gift from my parents that I didn’t report, and inflated my paltry income when my wife and I bought our first home.

But the Sungs never gave loans to people who were unprepared to pay them, like the Big Banks did. Abacus knew their community and helped build their community. And that means understanding there are special realities in any immigrant community that demand a different way of assessing the worthiness of receiving loans. This historic reality was completely dismissed by the DA’s office. I don’t see the Sungs crossing any ethical boundaries. They are among the most principled people I’ve ever filmed.

Did you foresee the verdict? Please describe the anticipation you felt as a filmmaker.

We did not foresee the verdict, which I am loathe to discuss in detail here because part of what makes this film compelling for audiences is that they don’t know what’s going to happen since this is a story that never broke through in the mainstream media. I will say that the long deliberation was nerve-wracking for everyone.

How are the Sung family and Abacus bank doing now and what impact would you say the indictment had on them?

The Sungs say that they lost money as a banking institution during the three-year period between the indictment and the trial. This was due in part to the fact that Fannie Mae was not permitted to do business with Abacus because they had been identified by the DA’s office -- against their will -- as being the “victim” in the case. Abacus did a lot of business with Fannie Mae (and made them hundreds of millions of dollars) and it was a big blow to them. The demands of the trial, financially or emotionally, didn’t help Abacus’ business either.

What do you think should have happened to the "too big to fail" banks during/after the crisis? Should there have been indictments?

I believe that not only should the Big Banks have been indicted, they should have been broken up as well. They are too powerful, and a number of economists warn that we could be headed to a similar catastrophe given the kid-gloves treatment they have received by the government.

"Hoop Dreams" will undoubtedly always be the film you are measured by (despite "Life, Itself," "Interrupters" and others). So, I'm going to ask: Is it fair to call this film a departure for you?

Yes, this film is a departure from "Hoop Dreams," "The Interrupters" and films of mine like those that are observational and somewhat gritty at their core. But across my career I’ve had several departures. "Life, Itself "certainly was. The ESPN film, "No Crossover: The Trial of Allen Iverson," was as well. It wasn’t possible to make a more purely observational film with "Abacus" because we had limited access; we weren’t allowed in the courtroom, or into the deliberations of the prosecution and defense teams.

I believe that filmmaking is always about adapting to the reality you are faced with and trying to make the best film you can make, rather than adhering to a certain “style” that has worked in the past. Besides, I like trying to stretch myself. I welcome opportunities to try to tell stories in different ways.

Shares