For a small but devoted following, the generation of postwar white American dudes that produced so many professed or self-professed Great Writers — roughly speaking, from Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo to David Foster Wallace and Jonathan Franzen — had one major unsung hero. His name was Denis Johnson, and he died last week of liver cancer at his home in Gualala, California, a community on the Sonoma County coast whose particular brand of madness was brilliantly captured in Johnson’s 1997 novel “Already Dead.”

On the first page of that book, Johnson describes “the small isolated towns along U.S. 101 in Northern California” — places like Gualala, in other words — as “places a person could disappear into."

They felt like little naps you might never wake up from — you might throw a tire and hike to a gas station and stumble unexpectedly onto the rest of your life, the people who would finally mean something to you, a woman, an immortal friend, a saving fellowship in the religion of some obscure church.

The novel’s protagonist has encounters much like that, which compel him to “acknowledge the reality of fate, and the truth inherent in things of the imagination.”

That was the contradictory truth Denis Johnson always sought. Like so many of his books, “Already Dead” would have won awards and been recognized as a masterpiece in a slightly different, less stereotype-encrusted world. If there’s a funnier, more exciting and more deeply penetrating novel about how and why the California dream went off the rails, I haven’t read it.

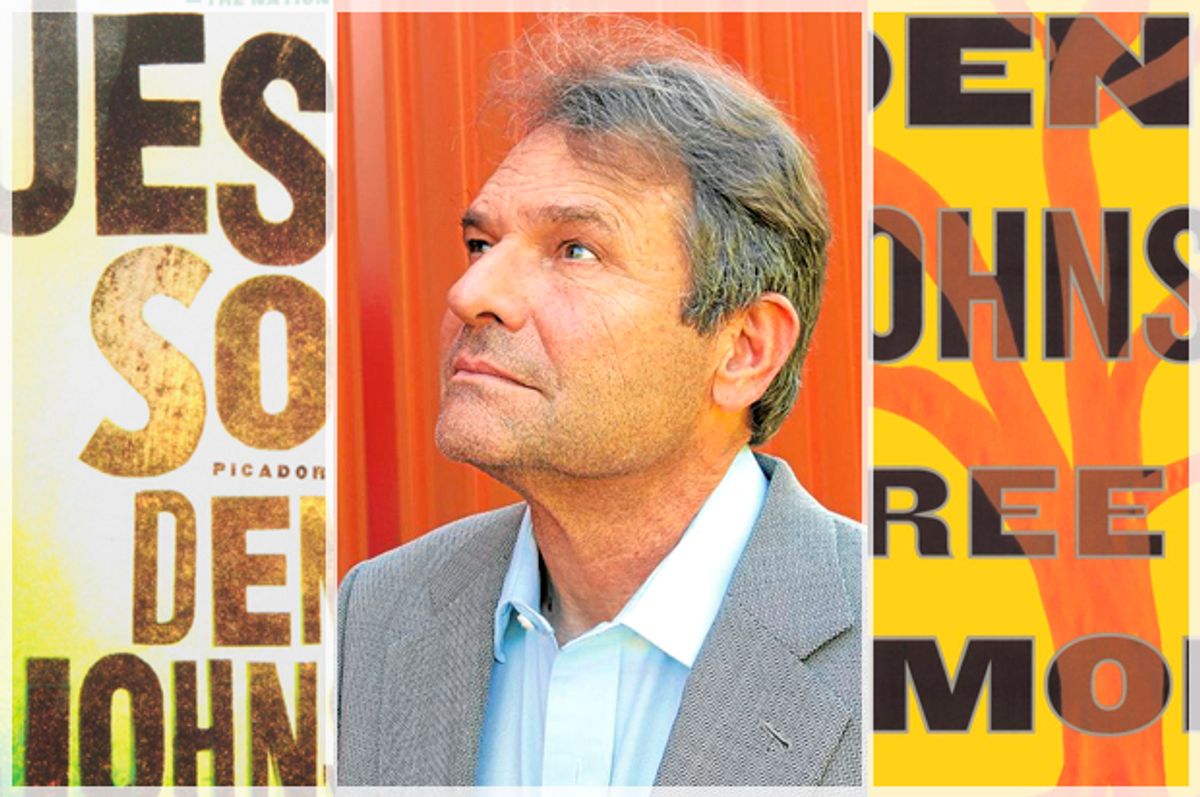

Johnson was only 67 years old, and while his health had been perilous for some years — thanks in part to his acknowledged history of alcohol and drug abuse as a young man — his fans and followers (which include me, obviously) have been dealt a crushing blow. He leaves behind 10 novels — none of them a best-seller or even an unqualified success — a handful of poetry collections, a couple of plays, some scathing, unforgettable nonfiction essays and journalism and one famous short story collection. That latter book, for better or worse, defined his career.

That collection was called “Jesus’ Son” and was published in 1992, although several of the individual stories had appeared in The New Yorker over the preceding decade. It was a series of semi-autobiographical vignettes about a drifter, drug addict and petty criminal moving across the underbelly of Reagan-era America with no apparent purpose. Its first story, “Car Crash While Hitchhiking,” begins with a famous oracular passage:

A salesman who shared his liquor and steered while sleeping. . . . A Cherokee filled with bourbon. . . . A VW no more than a bubble of hashish fumes, captained by a college student. . . .

And a family from Marshalltown who headonned and killed forever a man driving west out of Bethany, Missouri

If the first-person yarns of “Jesus’ Son” struck some readers as documentary realism, they were anything but. Johnson was self-consciously writing in the lyrical-minimal tradition of Ernest Hemingway and Raymond Carver, who had been Johnson’s teacher at the famous Iowa Writers Workshop. Johnson himself said he had borrowed both structure and theme from Isaac Babel’s “Red Cavalry,” a legendary work of early Soviet fiction that on the surface seems like an entirely different kind of collection.

“Jesus’ Son” is a memorable and striking book, which for some years was passed around in creative-writing classes as a sort of secret gospel. But the problem it created for Johnson’s career was one that he never entirely overcame. He was widely understood as a literary expert in drugs, crime and debauchery, when in fact he was only interested in those phenomena as symptoms of other, deeper disorders that could not be seen. Any significant reading of his work makes clear that he was more concerned with the spiritual and moral narratives he perceived beneath the surface of American life — with “the truth inherent in things of the imagination” — than with its superficial details, much as he relished depicting those in grotesque or hilarious detail.

Later in life Johnson defined himself as a Christian writer, but he didn’t mean that term the way Americans are most likely to receive it. To use a reference he would have appreciated, Johnson understood the American story largely in terms of William James’ “Varieties of Religious Experience.” He perceived a fundamental unity, for example, between the supposedly nihilistic drug culture of the ’60s and ’70s and the supposed patriotic idealism that drove the disastrous war in Vietnam. Both were aspects of a visionary, transcendental and/or delusional sensibility that had defined Americans’ sense of themselves and their nation clear back to the Puritans’ “City on a Hill.”

Those themes came together most visibly in “Tree of Smoke,” Johnson’s National Book Award-winning Vietnam War novel, published in 2007. Full of wit, brutality and imagination, the book is fueled by Johnson’s refusal to default to easy political formulas and his remarkable ability to render warring states of mind and states of myth. But “Tree of Smoke” is also maybe a bit hemmed in by the lugubrious tradition of the “Vietnam novel” and an aspiration to DeLillo-like bigness.

I love or at least admire all of Johnson’s work, and more than anything I admire his Joan Didion-like or Joseph Conrad-like ability to see connections and correspondences other people can’t and to not care whether he is “on message” or “capturing the Zeitgeist” or whatever other cliché is translated as “stating the obvious.” I largely agree with my former Salon colleague Laura Miller’s contention that Johnson was at his best — and his most profound — when he used genre fiction as a container, as in the aforementioned, masterful “Already Dead” (a crime novel and a “California gothic”) or the purposefully pulpy late thrillers “Nobody Move” and “The Laughing Monsters.”

We will never get to read Denis Johnson’s novel about the Donald Trump era, but in a sense he’s been forecasting it for decades. Trump feels like a construct imagined by one of Johnson’s drunken or drug-fueled characters, either in fear or longing or both — what if we could have a president who was absolutely nothing like a goddamn president? — who clung on somehow into the realm of so-called sobriety. Johnson would have insisted that even such a person as that possessed identifiable human passions and longings, an inner life, and even those of us who claimed to not be responsible had collaborated in willing him or dreaming him onto the national stage. He would also have understood that we weren’t ready to listen and why.

Shares