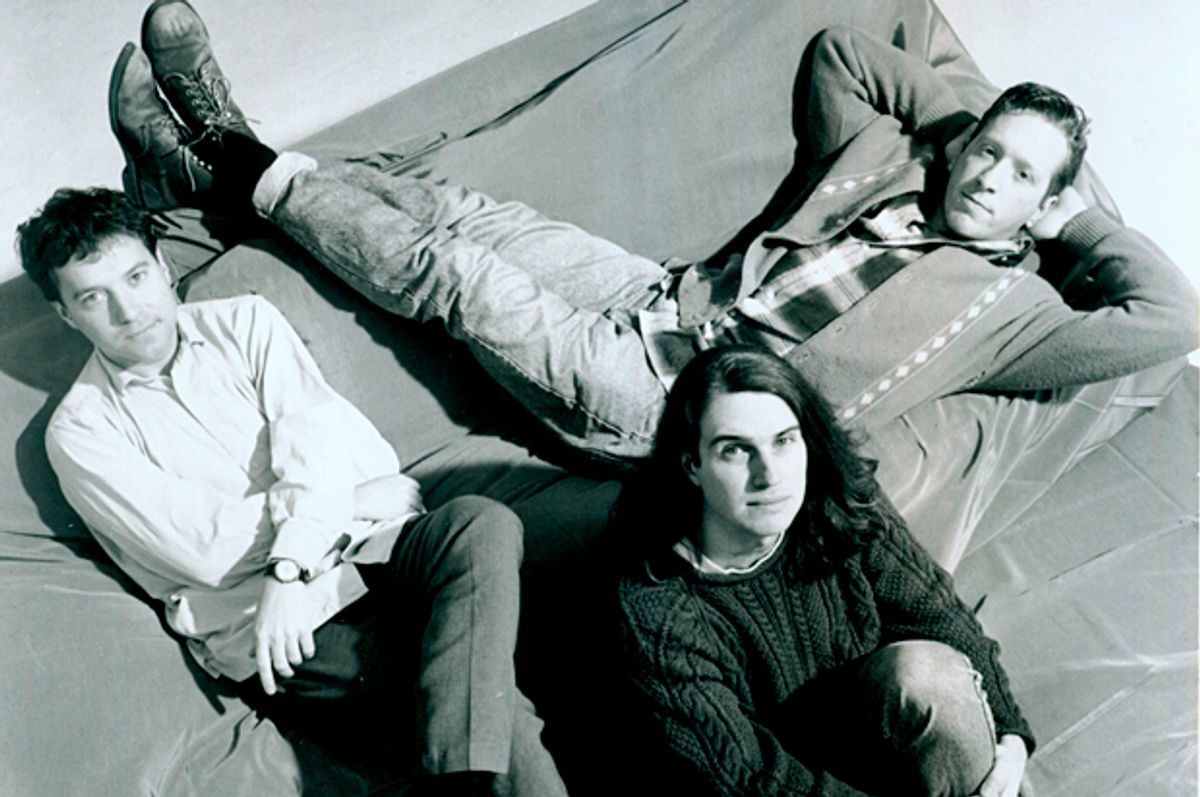

For Buffalo Tom, 1992 was a pivotal year. The Boston trio — guitarist Bill Janovitz, bassist Chris Colbourn and drummer Tom Maginnis — released its third album, "Let Me Come Over," which was reissued on May 19 with a ferocious live concert, "Live From London, ULU, 1992."

Released on respected indie label Beggars Banquet, the record finds the band dabbling in sophisticated, old-soul songwriting. Although there's no shortage of bristling rock 'n' roll (the springy power-pop highlight "Velvet Roof," melodic grunge-pop "Stymied" and thrashing "Darl" and "Saving Grace"), evocative songs such as "Larry" possess a dream-pop vibe and "Frozen Lake" is a keening ballad driven by plaintive acoustic guitar.

Then there's the slow-burning, anguished "Taillights Fade," which Janovitz performed live with Pearl Jam's Eddie Vedder a few weeks ago at a Boston benefit concert. The song captures someone looking back on their life, drowning in regrets and realizing they can't undo their past.

After the record's initial release, Buffalo Tom played major music festivals (Reading, Pinkpop), and had videos for the songs "Velvet Roof" and "Taillights Fade" receive MTV airplay. In the ensuing years, the band had an MTV and alternative radio hit ("Sodajerk"), toured all over the world and performed on "My So-Called Life," among other things.

Janovitz called Salon on a break from the studio, where he was working on a new Buffalo Tom record with producer Dave Minehan. "There's definitely some classic Buffalo Tom songs — classic in our minds, anyway," Janovitz says. "And then there's some stuff that we're stretching out in some different directions.

"Some of my more recent side project stuff, I've done some more linear groove-type, Feelies groove, or machinated-beat kind of groove," he continues. "More like getting into this New Order vibe, [or] Television, or something like that. We have a song that's sort of like that. I mean, it all sounds like Buffalo Tom at the end of the day. But we did do a more overtly Stones-y song with backup singers and stuff. It's more of a ballad than like our old song "Treehouse," where we had background singers. That was more of an upbeat thing. This is more of an almost "Exile"-ballad type thing."

I revisited "Let Me Come Over" before this interview. What struck me is there is such old-soul songwriting on it. You guys weren't that old when you wrote it, but there is just this melancholy tint to the record that's really timeless. What was your mindset going into that record?

We had just come off of what I felt was almost one big debut. Our first and second records [1988's SST Records-released "Buffalo Tom" and 1990's "Birdbrain"] were almost part of the same thing to me. I think we were more or less done, or at least sort of started that second record, before we even really went out on tour.

By the time we got to "Let Me Come Over," we had come from college, basically, to these fairly big stages in Europe. We were starting to get around the States a bit. But it was still very much an indie [label] thing, SST and Beggars Banquet. That was "making it" to us. There was no "beyond that." We were just thrilled to be part of all that, to be part of that circuit that was in [the book] "Our Band Could Be Your Life," that whole scene. It was really much like "Wow, so we got to do a record. Excellent. Do we have to go back to life now, after we've graduated college, and go get a real job? No, we get to do a second record!" And the second record is doing pretty okay, and now we get to do a third record.

["Let Me Come Over"] was the first off-the-road record, so maybe that's where some of the weariness comes from. And some of the melancholy [comes from] being away. My wife and I are going to be married 25 years this year, and we've been together since college, so it's been over 30 years. That separation was really tough back then. I was gone for two months at a time and then back for a few weeks and back out. So there's a lot of that in there. I mean, like "Saving Grace," that song had a lot of "can't wait to get home" kind of stuff, and "Crutch" has a bicoastal, San Francisco and Boston communication.

If I look at more of a bird's-eye view of that record, it's just really what you're like in those post-college years for a lot of kids like us, that grew up in the suburbs or whatever and got college educations. Now people are dispersing around the country, if not the world. And here we were, going to see people that were friends of ours in different places, coming back home and learning to be domestic, to some degree. [Laughs] How to wash dishes and do laundry and to have a cat. All of that stuff is in there.

And there's so much anxiety around that time, too, because you're not quite sure what's going on. You feel like everyone else but you have things figured out, even though that's not actually the case. I still remember that so vividly.

I would say that came from me a little bit later. I felt like I had the world by the balls at that time. It was like, "Are you kidding me? I graduated with some ridiculous degree in communications and comparative literature, and I already have this life lined up for me. What a way to spend your twenties!" That's undeniable. A lot of my friends are just like "I don't know, I'm going out to San Francisco, I'm tending bar."

By the time [Buffalo Tom] took a break around '99, we were certainly the old men out on the circuit, to some extent. And, by that time, some of our friends were on their second kids and second jobs and, in some cases, second wives. [Laughs] Those '90s went by so fast for me. By "Let Me Come Over," I was still very much like, "No, man, this is amazing. Are you kidding me?" And I had it in the back of my mind that it would all catch up with me somehow. And it did. [Laughs] That's what happened at the end of the '90s

That live record that's packaged with the "Let Me Come Over" reissue is such a confident document. You can tell that you guys have been on the road and working on this stuff. It's very consistent and solid.

That's why those first two records sort of feel like an A-side and a B-side to me. The first record ["Buffalo Tom"] is not very dark; the second record, "Birdbrain," I felt was pretty dark overall in tone. And then this third [one], we were just finding our way and trying to feel what was good songwriting.

I had never really sung in a band before that first record. And Chris and Tom had never played their respective instruments before forming Buffalo Tom. It took those couple of years on the road to get to "Let Me Come Over," to really find our footing and find our songwriting wheelhouse.

Chris was starting to write more, and both of them just felt more and more comfortable piping in on my songs — quote-unquote my songs. We really were a committee, in mostly a good way, very much a democracy. And we always took songwriting credit as a band. There was very much a freedom in the rehearsal room to change things up. It wasn't like one guy saying "Here's what you're going to do in my song."

As you were mixing the live record recently, was there anything that struck you about listening to that document from back in the day, or from listening to yourselves from 25 years ago?

The constant thing that strikes us when listening to any old document of us is the energy and the speed with which we played. [Laughs] We're trying to relearn some of these songs here, or review them, and we're like "Wow, that was fast" or "Wow, we really played that fast back then."

I had sort of known about this live thing for a while. There's a ton of stuff out there, relative for a band of our size — live bootlegs or whatever. And this one was actually commissioned. Nobody seems to remember the circumstances, or who commissioned it, but there was a three-camera or four-camera shoot and a 24-track truck. Somebody at Beggars must've done it, but Beggars can't seem to find the video master of it. It's on YouTube. It's just a nonstop stream of stage divers off the stage. [Laughs] And that really brings me back in time.

I have this rough cassette, rough mix of that show. The rough mixes just sounded fantastic, sonically, and the energy was there. So I recalled that I had some 24-track reels up in my attic. I mean, I have a ton of them. But I thought that maybe I had at least some of that show, and it turns out I had the entire show. So we just brought them down to the local studio, Q Division in Somerville [Massachusetts], and this guy Pat DiCenso did a really great job mixing it.

The people that heard it were just kind of like "Wow. You guys were almost like [exuding] Who-like level of energy back then." I mean, I think we haven't lost much for 50-some-year-old guys, but it is remarkable to hear that young, sprightly spark.

There is something about seeing a band when they're like just a couple years into their career. It's kind of an intangible thing. They're so excited, and they're jazzed to be doing that.

Yeah it's a mix of sort of youthful, whatever, adrenaline, testosterone and beer. [Laughs] And just being excited to be playing at this big venue in London. I mean, I had never been off the East Coast before I was in Buffalo Tom. I graduated college without ever getting out West. In fact, I think we went over to Europe before I had even gotten out to the West Coast. So it was a very exciting time.

How did Buffalo Tom end up being on "My So-Called Life"? I think that was my introduction to the band, seeing that episode. I'm sure I'm not alone in that too.

No, no. I mean, if you look at this video, for example, of the ULU show in 1992, it's predominantly dudes. And that was in England. It wasn't much different in America. We used to joke about all these sort of emotionally constipated guys in white baseball caps that said "Cocks" on them, you know. [Laughs] They had all their checkered shirts, and you'd see them maybe at the Dave Matthews shows as well. [Laughs]

We went from being that SST, post-'80s sort of rock [that was] artsy, but we were much more . . . Most bands feel like they don't really fit into everything, but we felt a little apart from it.

Some fans at ["My So-Called Life"] were music fans, and clearly there was a Boston connection. I forget who it was, one of the producers really liked . . . I think The Lemonheads were in there, but Juliana [Hatfield] was a guest star in [an episode]; she [played] an angel.

And I remember hearing about that show. My wife might have already been a fan by the time they approached us. It hadn't been on long — in fact, it was only on for a year? Or two years?

Yeah, just one season.

But it had an outsized influence. And they just asked us, and we said "Sure." I mean, my wife was thrilled. She was older than the demographic, but it really spoke to her about her experience when we were in high school in the '80s. It was a great experience doing it. The kids were amazing. Claire [Danes] was only 15 at the time, and they were so unabashed. They were so unjaded, they all showed up and hung out in our trailer and asked us what it was like to be a band. They just really wanted to talk about bands, and what it's like to be on the road. We were sort of like elder statesmen. It really made us feel old.

But then after that show, the impact was instant. All of a sudden, we started seeing a bunch more young, pretty women at our shows. [Laughs] I mean, any women was a welcome addition for our crowd. But [you'd see] these sensitive girls still, really, who are just maybe turning 21 and able to come to clubs. It was just great. It was excellent when we finally broke through a little bit.

It's so funny to think that one thing can change the course. The show had a cult following, too. I saw the show later on MTV because it had gotten canceled; ABC had no idea what to do with it. That's so great people found it, and people found you guys.

Our philosophy was to mostly say yes to things. There were a couple of things that I said no to, and then had to say yes to. For example, there was a show called "Catwalk" that was this syndicated Canadian version of what it must be like being in a band. And of course there are all these people you might see in the vampire movies; they're just, like, sultry-looking. These are not people in a rock band; they're all models and all living in a loft quote-unquote together. It was just this ridiculous show that my wife and I used to make fun of when it would come on.

And they were fans, and they asked us to be on. And I said, "No, no, no, no thank you, no thank you." But MTV had put a lot of stock into it. I remember getting a call — I remember it vividly -- I was in Indianapolis at some stupid motel on the road. My phone rings, and I pick it up, and [affects executive voice] "Bill, this is Danny Goldberg." Danny Goldberg, the head of WEA Records, and of course Nirvana's manager.

And he says [affects executive voice] "Look, Bill, MTV is not the mafia. They're not going to break your legs if you don't do 'Catwalk.' But it can't hurt to do 'Catwalk,' you know. We'd really like you to do 'Catwalk.'" So what do I do if the head of the label calls and says he wants you to do "Catwalk"? We did "Catwalk." [Laughs]

I was hoping it would just go away, and nobody would see it. Nobody else that I knew of knew about it. But of course it did [start] to get played big time on MTV [later]. We were in San Francisco doing a string of West Coast dates. And Tom, our drummer, got really sick and he couldn't play. Chris and I said "Well, let's do the San Francisco show as a duo." So we did that, but some guy was holding up a sign in Slim's in San Francisco. He kept going "Bill! Bill!" And I would look over, and he's got this sign that says "'Catwalk.' Why?" [Laughs] It was like my worst nightmare.

That's hilarious and ridiculous.

He had made the effort of making the sign and bringing it into the club . . . We've done worse. I mean, it wasn't a horrible [TV] show, and we were flattered. And we were nice to them, of course, and they were nice to us. But it was a silly show.

A lot of that stuff is inherently silly. You have to kind of embrace and go with the absurdity. You realize it's kind of weird, but kind of fun too.

To some extent, most things felt that way at a certain point. So early on, we really — I must emphasize we didn't have any expectations of going beyond a couple of records. But getting back to "Let Me Come Over," while that was coming out, or while it was out, "Nevermind" came out. Everything changed after "Nevermind." It really became B.C. and A.D. for bands that played guitars and wore flannel shirts. And it changed everybody's expectations.

The people that were in college radio when were were kids in college, or people that were at SST Records, and people that were managing bands, like Janet Billig — these people were getting to be in actual positions of power to make or break bands like us. For a while, the lunatics were running the asylum, in a good way. And we were mostly beneficiaries of that post-Nirvana success.

I mean, there are many bands that were coattail riders that came in and were just watered-down versions of it. Of course, that's exactly where it eventually ends up; it just ends up at the lowest common denominator. But if it hadn't been for that, can you imagine a time where Pavement was as big as they were, or Teenage Fanclub were on "Saturday Night Live" because they're on Nirvana's label?

There was all that cool stuff, but then there was a lot of weird stuff. Like, all of a sudden we're in Rock Cliché Land. Eighty percent of our lives was just battling back rock clichés. Opening up for this band Live was kind of a miserable tour. They seemed to be taken with this whole rock star idea, like "We're going to go out to strip joints, we've got a security detail, and we're going to take limos." And [I'm] just going "Really? I didn't think this stuff still happened."

A lot of those bands were sincere, and were the sensitive types. You'd never think they would do something like that.

And I hate to throw people under the bus like that, but I keep coming back to Live. They struck me as that kind of fake earnest, you know, drama thing. We couldn't stand on the side of the stage during Live's set, because it might . . . I don't know, who knows what. So we didn't see Live for, like, four weeks, because we weren't allowed to stand on the side of the stage. [Laughs]

We would be back at the hotel bar out on the highway somewhere, because we were never in cities on these shed tours. At eight o'clock, our night would be over, and we'd be like "Shit, now what do we do?" Just developed a bad drinking habit — more so, I should say. [Laughs] But the beauty of that particular tour was that we were sharing the bill with Big Audio Dynamite. And so many nights, we were just hanging out with Mick Jones of the Clash. For every negative, there's a positive. [Laughs]

Shares