When President Donald Trump announced that the United States would withdraw from the Paris climate agreement, California elected officials were immediate leaders in the reaction, promising to forge ahead regardless of what Trump might do. They were building on an existing infrastructure of 175 subnational entities committed to fighting climate change, the Under2 Coalition, which California helped initiate.

This leadership was not unexpected, as a new poll from NextGen Climate found that 76 percent of Californians believe transitioning to clean energy will help California’s economy and 68 percent say they are “proud” of California’s leadership on climate change. Still, leadership was welcome.

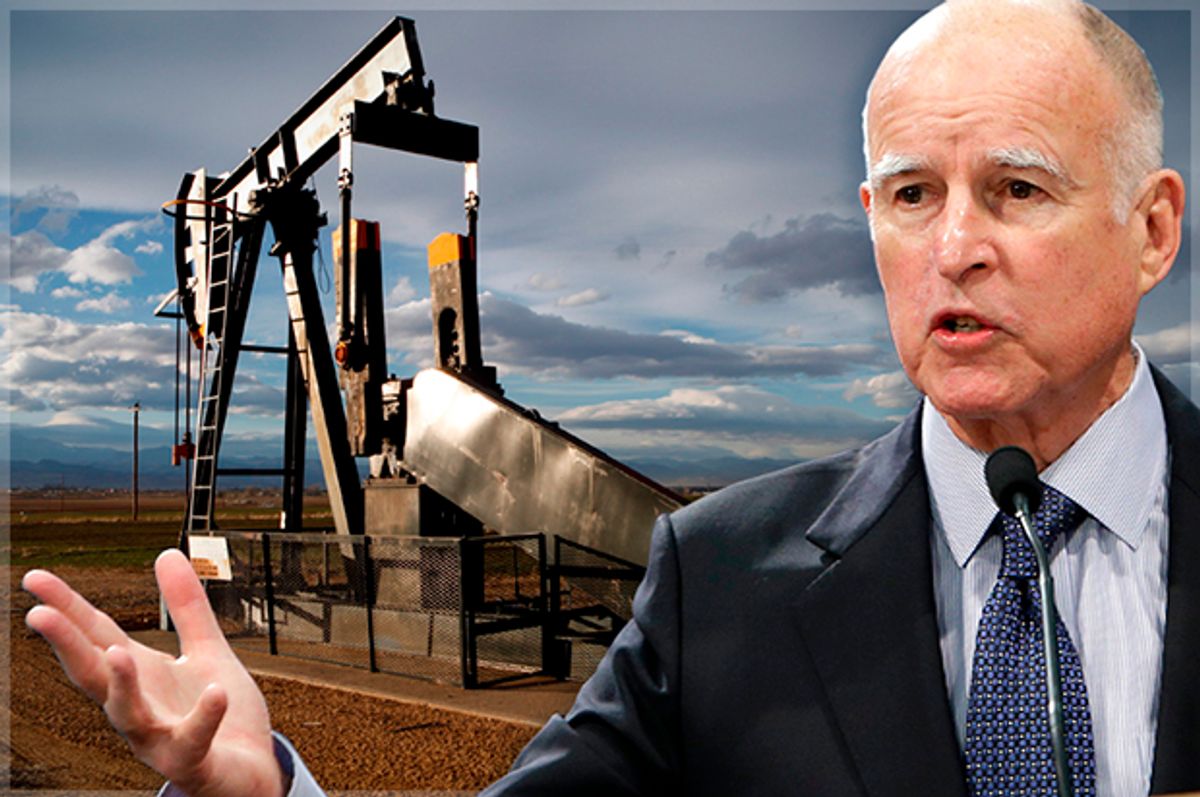

Gov. Jerry Brown joined with New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Washington state Gov. Jay Inslee to announce the formation of the United States Climate Alliance, pledging it would “help fill the void left by the federal government.” By the next day, seven more states had joined.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti was the lead signatory on a statement from 187 “climate mayors,” representing 52 million Americans, pledging to “adopt, honor, and uphold the commitments to the goals enshrined in the Paris Agreement.” Altogether, 34 California mayors signed onto the statement.

State Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León sent Brown a letter signed by all 27 of the body's Democrats calling for the governor to convene a climate summit to "partner with Mexico and Canada, and invite like-minded states and subnationals from around the world, to ensure that we continue to charge ahead without forfeiting all of our historic progress to date.”

That was just the first day, a taste of much more to come, as underscored vividly by Brown’s subsequent trip to China, where he signed a number of significant climate agreements.

But the day after de León's letter, June 2, revealed a strikingly different side of California climate policy and politics — a side that’s been there for much longer. A contingent of about 50 mostly Latino activists and residents shut down a Los Angeles meeting of the largest regional air quality board in the state, protesting approval of a project with significant climate impacts as well as public health impacts on neighboring communities of color. The project would combine two existing facilities owned by Tesoro to create the largest West Coast refinery, and significantly increase its processing of "dirty crude" — Canadian tar sands oil and Bakken crude oil — the most environmentally harmful forms of crude oil coming to market.

“This is a crude oil invasion,” Jack Eidt of SoCal350.org told me, and Julia May, a scientist with Communities for a Better Environment (CBE), shared transcripts supporting the claim. “The head of Tesoro Corp. repeatedly states to their investors, in many different forms, that they're going to bring North Dakota Bakken crude ... and about 25 percent Canadian tar sands crude by rail to Vancouver, Washington, where they’ve got an application for a rail ship terminal, and then they bring it back to L.A.,” May summarized.

So far, however, the South Coast Air Quality Management District has ignored those plans completely. “The district's line is, ‘Oh, well -- refiners use a lot of different crude oil and so these other projects happen independently of the refinery modifications. So we don't even have to evaluate that,’” May said. “It's just baloney.”

What’s more, as CBE noted in its comments on the plan, the project "combines the two worst polluting facilities in California" in terms of damaging impacts on communities of color. A new study just released by Fluxsense, a Swedish technology firm, revealed that actual pollution levels at refineries were significantly higher than previously reflected in the data used in the environmental review process. As CBE noted, Tesoro’s emissions of cancer-causing benzene were 43 times higher than reported, and emissions of other dangerous compounds like gasoline and kerosene were 6.4 times higher.

“The data was not ignored,” Air Quality Management District spokesman Sam Atwood responded by email. “It was evaluated by staff who determined that the FluxSense study did not evaluate or demonstrate the use of this technology for predicting emissions from tanks to be built in the future.”

“The district’s response is unfortunately nonsensical,” May countered. There’s no reason to wait years before adopting more accurate measurements, she argued. Environmental reviews “are required to be evaluated based on actual conditions, not solely on emissions factors," which is the method currently used.

“We don't have our environmental laws in place to get the benefit of the doubt to polluting industries,” Earthjustice attorney Adrian Martinez pointed out. “They’re structured to give the benefit of the doubt to breathers, so that we're not putting people in harm's way.”

The situation was so dire, that Tesoro was selected as the focal point for the Southern California People’s Climate March, which drew between 5,000 and 10,000 people. Rather than marching through Hollywood, Santa Monica or Malibu, L.A. activists chose to rally and march on Tesoro headquarters.

Sen. de León was one of the featured speakers that day, along with actress and activist Jane Fonda. Those "who live here near the Tesoro Refinery are on the front lines," Fonda said, "in the neighborhood known as the ‘sacrifice zones.’ They and their families are the vulnerable victims of cancer-causing benzene and daily exposure to all the other toxins refineries spew into our air and water. I have been to Standing Rock, and it is true what they say: Standing Rock is everywhere.”

With all that in mind, CBE decided to stage an action disrupting the proceedings of the air-quality board, “because we feel that AQMD disrupts our life in a big way,” as organizer Alicia Rivera told me. The protesters' primary focus was to heap shame on the board for failing to listen to them for more than three years, for leaving the decision to district executive officer Wayne Nastri, and for failing to investigate the impacts of dirty crude, which the board had promised to do in 2010 but never did.

“You washed your hands! You washed your hands! You put all our lives in one person's hand.” the group chanted as Rivera concluded her remarks to the board.

“They already rubber-stamped the decision, without evaluating the impact of that dirty crude,” Rivera told me afterwards. “That’s why I said we believe that they evaded responsibility on this significant issue by putting all the power on the executive officer."

"Shame on you!” the chants continued. “Shame on You! Shame on you!”

Protesters had expected to escorted out after a few minutes, perhaps even arrested. Instead, the board abandoned the meeting and secretly resumed in private, an apparent violation of California’s public meeting laws. Video of the original meeting was removed from the web, and only partially restored (with the demonstration and all that followed edited out) more than 10 days later.

Prior to the decision, there had been mounting political opposition. City governments of Los Angeles, Carson and Long Beach all called on AQMD to slow down and take a more critical look. A mid-December letter from L.A. Mayor Garcetti echoed many of CBE’s concerns.

“The potential increase in air and water pollution, upstream greenhouse gases and international safety hazards related to the use of Bakken crude require a broader environmental analysis through your recirculation process,” Garcetti wrote. He also cited the largely Latino neighborhood of Wilmington, near the refinery site, “as a ‘disadvantaged community’ under our Clean Up Green Up policy" and "a key environmental justice benchmark" in L.A.'s citywide sustainability plan.

Both ideas — comprehensive environmental analysis and prioritizing environment justice — exemplify California’s opposition to Trump. But putting them into practice is another matter.

“California really is a tale of two states,” said CBE president Suma Peesapati. “This is so representative of the two faces of California, where we have Jerry Brown and representatives from state government independently going to these climate talks in Paris, and representing California as independent from the country. At the same time, all over the state these refineries are being retooled to bring in dirtier crude, and we’re fighting coal exports from California, even though California doesn’t produce coal. ... But in terms of disproportionate impact on communities of color, that’s nothing new. It’s the same old same old."

“Gov. Brown talks a very good game on climate,” said R.L. Miller, founder of the Climate Hawks Vote super PAC and chair of the California Democratic Party’s environmental caucus. “However, he's proven himself completely unwilling to turn off California' oil spigot -- the state is still one of the nation's top producers of oil." When it comes to "forbidding fracking or the Tesoro merger," Miller continued, Brown "simply won't say no.”

California's governor did not personally approve Tesoro's plan, as Jack Eidt of SoCal350 pointed out. “He has, however, assented to extreme drilling, continuing with Aliso Canyon [a leaking gas storage facility], enabling Big Oil, and possibly supporting offshore drilling.”

“I think we’re looking forward to having a different governor, because he is not environmentally friendly,” Eidt noted, pointing to “all these different types of extreme drilling procedures" that Brown refuses to touch, which have proliferated around the state in recent years. “He could be worse, as we see what's happening with the president. But he’s not nearly good enough for what is necessary.”

Eidt isn’t alone in his views. When Brown spoke at the Democratic National Convention last year, one faction of the California delegation cheered his name, while another loudly chanted, “Ban fracking now!” More recently, a February report from Consumer Watchdog, endorsed by a dozen other groups, rated Brown's record in seven key issues. It found Brown’s record to be "green" on only one issue — greenhouse gas emissions — "dirty" on four, and "murky" on two others. What's more, two of the "dirty" issues cut directly against his climate policies: fossil fuel-generated electricity and oil drilling, on which Brown was faulted for nurturing drilling and fracking, and firing regulators who were making drilling safe.

But Brown isn’t the source of problem, only its most prominent indicator. Michael Mishak’s report from the Center for Public Integrity, “Big Oil’s grip on California,” cut to the heart of the problem:

Over the past six years, as the state has won international praise for its efforts to fight climate change, Big Oil has spent more than $122 million on campaign contributions and on lobbying to boost production, weaken regulatory agencies and mold energy policy.

Perhaps more than any other special interest, the oil industry has helped reshape California’s political landscape, in part by cultivating a relationship with Brown and nourishing a new breed of Democrats: moderate lawmakers who are casting a critical eye on the state’s suite of climate-change policies.

While there are many moving parts to the story, two underlying elements stand out: First, Jerry Brown’s decision to compromise with big oil, to stave off their opposition to Proposition 30, his 2012 tax increase initiative primarily targeting the rich; and second, Big Oil’s aggressive exploitation of California’s new “top two” open primary electoral system, which has often produced races pitting two Democrats against each other.

As the report explains, “industry wooed moderate Latino and African-American lawmakers from urban and rural districts where energy firms tend to operate. These communities are often choked by pollution but also have some of the lowest voter-turnout rates in the state.” Thus, a “good government reform” touted as “giving voters more say” has actually done exactly the opposite.

Indeed, the region's second-biggest recipient of oil money, Isadore Hall, was the Democratic establishment pick to succeed retiring Rep. Janice Hahn last year, for the district in which the Tesoro refinery sits. But Hall beaten by Nanette Barragan, an L.A. city council member and grassroots leader in defeating an oil industry initiative to drill along the Santa Monica Bay.

As Mishak’s report makes clear, Brown’s relationship with Big Oil is complicated — cooperating in some ways, while clashing in others — and the same is true throughout California politics. While courting their support for Prop. 30, Brown fired two top regulators, Elena Miller and Derek Chernow, who refused to go along with industry-supported regulatory evasions to speed up the spread of fracking. But he still pushed legislation they opposed, as well.

In a sidebar to his report, Mishak notes, "Four years of emails obtained by the Center for Public Integrity suggest a comfortable — at times, chummy — relationship between Gov. Jerry Brown’s appointees and the industry." In 2014, he reports, regulators who were developing rules for fracking appeared at public meetings organized by an oil industry lobbying group called WSPA, in an effort to calm public concerns:

Before a gathering with farmers, officials with WSPA and the Department of Conservation coordinated their presentations. ... “I think you SHOULD present yourself as the regulator,” WSPA VP Tupper Hull wrote [to the department’s deputy director]. At an earlier meeting, he said, “Some folks thought the Department seemed a little too cordial with oil. Be hard on us.”

That snapshot captures the Kabuki-theater character of California climate-change politics in recent years. Such a choreographed performance stands in sharp contrast to the organic rowdiness of the group that accompanied Rivera in shutting down the AQMD meeting, chanting “Shame on you!”

Which kind of theater will ultimately prevail is difficult to say. The odds still favor Big Oil, a longtime political and economic powerhouse in the Golden State. But the façade is getting ever harder to maintain, as awareness spreads more rapidly than ever and the basic lines of the drama keep changing.

“On the one hand, I'm genuinely excited for the state/local Paris replacement agreements that are springing up, such as the (state level) Climate Alliance and (local) climate mayors,” Miller said via email. “But on the other hand I'm especially cynical about the mayors given city boundaries and limits.”

For example, she asked: “Will Mayor Eric Garcetti actually do something about the urban oil fields in Los Angeles adjacent to neighborhoods and schools?" Or will Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia, whom Miller calls a "lite green" politician, "have the political courage to shut down fracking and thus a good portion of the city's revenue?”

Whether Californians will get more Kabuki theater or real action on the most crucial climate issues remains to be seen. Seeing through the theatrics to the true nature of California's double-edged climate policies is an important first step.

Shares