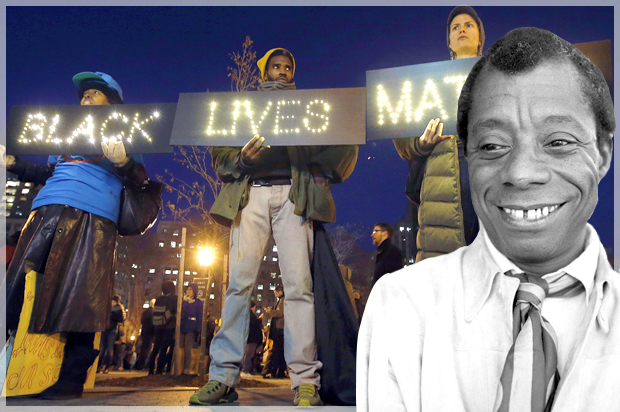

James Baldwin, buried on December 8, 1987, often looks like today’s most vital and most cherished new African American author. This impression doesn’t rest on the faith in bodily resurrection that Baldwin abandoned along with his teenage ministry in Harlem. Nor does it slight Teju Cole, Natasha Trethewey, Kevin Young, and the rest of the emerging literary competition — though it’s true that one leading light in that competition, Ta-Nehisi Coates, has suffered as well as profited from Toni Morrison’s pronouncement that he fills “the intellectual void” opened by Baldwin’s passing. Instead, the impression that Baldwin has returned to preeminence, unbowed and unwrinkled, reflects his special ubiquity in the imagination of Black Lives Matter. As Eddie Glaude Jr. observes, “Jimmy is everywhere” in the advocacy and self-scrutiny of the young activists who bravely transformed the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Natasha McKenna, and far too many others into a sweeping national movement against police brutality and campus racism. For these activists, disruptive and creative and warning of new fires next time, Jimmy himself has filled the void traced to his death. Something like the Shakespeare of Stephen Dedalus, the Baldwin of Black Lives Matter is his own true father — one who rehearsed for the role, it’s worth remembering, by raising several of his eight younger siblings and by peppering his live speech and written dialogue with the hip endearment of “baby.” With ironic paternalism, Baldwin habitually applied this sweet nothing to that set of permanent children proud of their whiteness. “So I give you your problem back,” he schooled a not especially fresh-faced interviewer in 1963, “You’re the nigger, baby, it isn’t me.”

It’s no state secret, of course, that Black Lives Matter, or BLM for short, is a movement fueled by electronic social media, by the graphic smartphone video followed by the mobile demonstration advertised on Facebook and choreographed in real time via Twitter. “The thing about [Martin Luther] King or Ella Baker” and the rest of the civil rights pantheon, explains DeRay Mckesson, the most prominent face of the movement’s techno-optimism, “is that they could not just wake up and sit at breakfast and talk to a million people. The tools that we have to organize and resist are fundamentally different than what’s existed before in black struggle.” Regardless of the new advantages of instant mass communication, however, BLM has also begun to reorder the slow time of the African American literary canon like the Civil Rights Movement before it. Whatever BLM’s cumulative political significance will be — the jury remains out amid white backlash, the election of backlasher-in-chief Donald Trump, the tragic assassination of police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge, and the slow fade of direct action as a defining BLM tactic — it has already adopted more than one literary muse and has already stamped black literary history.

Considered as a generational sensibility indebted but not confined to the #BlackLivesMatter platform launched in 2013, BLM has embraced a lyrically withering essayist, the previously mentioned Coates, and has appointed an academic poet laureate, the National Book Award finalist Claudia Rankine. It has recuperated a militant memoirist, Assata Shakur, whose 1987 autobiography, written in Cuban exile, now rivals “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” (1965) as a passport to 1960s-style Black Nationalism. The medley of poetry, radical confession, selective legal history, and anti-racist name-taking in Assata — an unexpected pre-echo of Rankine’s multigeneric collection “Citizen” (2014) — has also yielded BLM’s best-loved poem, a rewrite into rough ballad meter of the climax of The Communist Manifesto memorized and mass-chanted by thousands of protestors in dozens of American cities. “It is our duty to fight for our freedom,” Shakur’s twice-historical lines direct,

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains.

Yet while Shakur is the author of BLM’s “If We Must Die,” its street-tested anthem of unity-in-resistance, Baldwin reigns as the movement’s literary conscience, touchstone, and pinup, its go-to ideal of the writer in arms whose social witness only enhances his artfulness. It’s Baldwin’s good name and impassioned queer fatherhood that aspiring movement intellectuals invoke in Twitter handles such as #SonofBaldwin, #Flames_Baldwin, and #BaemesBaldwin. It’s Baldwin’s distilled racial wisdom, often mined from his heated Black Power-era interviews, that fortifies these intellectuals’ posts and tweets. (See, for instance, the viral social-media resharing of Baldwin’s correction of an Esquire magazine reporter in 1968: “I object to the term ‘looters’ because I wonder who is looting whom, baby.”) It’s Baldwin’s longer, formal prose that’s recommended by BLM protesters for its uncanny relevance, its vintage elegance combined with the tight fit with present emergencies that, according to rapper-activist Ryan Dalton, “says a lot about Baldwin’s writing, but also about how little progress we’ve made.” It’s the glossy black-and-white Library of America edition of Baldwin’s Collected Essays that rivals “Assata Taught Me” hoodies and DeRay Mckesson’s blue down vest as an iconic movement accessory. It’s the second thoughts on Richard Wright and retaliatory violence in Baldwin’s essay “Many Thousands Gone” that Rankine samples in detail in the “World Cup” section of Citizen. And it’s “The Fire Next Time” (1963), Baldwin’s unforgettable but often misremembered meditation on the Islam of Elijah Muhammad and the Christianity of and against Martin Luther King, that underwrites the whole of Coates’s “Between the World and Me” (2015), on whose dust jacket Toni Morrison declares the author the most gifted Son of Baldwin of all. Coates is happy to admit his bestseller’s steep debt to the older writer; the influence became inevitable, he tells us, after he reread “The Fire Next Time” and asked himself “why don’t people write short, powerful books like this [anymore], a singular, hundred-page essay?” One reason why more people don’t, it’s fair to say, is that Baldwin is now, practically speaking, back among us to write such books on his own.

Why is Baldwin’s work so alive in the tide of Black Lives Matter, flourishing more thoroughly now than during his own day of struggle, when King privately lamented his poetic license and Eldridge Cleaver of the Black Panthers publicly shamed the imaginary castration, extending “to the center of his burning skull,” he supposedly suffered as a black gay man? One reason involves an irony of history identified by the Paris-based African American writer Thomas Chatterton Williams. To Williams’s mind, the very “same characteristics of the Baldwin brand that so ‘estranged’ him from the concerns of his generation and of black America writ large—his intersectionality before that was a thing—are what make him such an exemplar of the queer-inflected mood of the Black Lives Matter era now.” In other words, for Williams, Baldwin’s variously queer misalignment with the social history of his present assures his model alignment with ours.

Williams’s observation may well exaggerate the extent of Baldwin’s alienation from his original cohort and country. Despite his many French and Turkish addresses and all the dim-witted, homophobic cracks about “Martin Luther Queen,” just how estranged from the evolving concerns of mid-century black America was this card-carrying senior member of SNCC, a nonviolent marcher from Selma to Montgomery who moved on to counsel Black Panther Huey Newton in a California prison? (Baldwin was far less estranged, it’s certain, than Ralph Ellison, the author of “Invisible Man” (1952), a fellow apprentice-turned-sworn enemy of Richard Wright’s social realism, and maybe the most deliberately American black author of any generation.) Williams is on the money, however, in suggesting that Baldwin’s renewed appeal is linked to the queer theory and queerer memory of Black Lives Matter. The movement’s queer leadership—Mckesson, Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and scores of others—refuses to think about race apart from the proto-intersectional Baldwinian question of race-and-sex-and-more. Their rebalancing of the history of black protest, designed to highlight what Garza dubs the neglected heroism of “Black queer and trans folks” along with black women, black prisoners, and other groups traditionally “marginalized within Black liberation movements,” enthrones Baldwin near the heart of the black progressive tradition.

BLM’s queer revisionism, a boost to Baldwin’s sales figures, is not the usual campaign to comfort an anxious radical present with the names and slogans of an admiring past. In the movement’s grasp of time after Michael Brown, a proudly improper civil rights epoch has escaped the prim tomb of Martin Luther King Day and has returned intact as neither tragedy, nor farce, nor civics lesson but as an urgent ethical test. “If you EVER wondered who you would be or what you would do if you lived during the Civil Rights Movement, stop,” commands Shaun King, the controversial BLM journalist. “You are living in that time, RIGHT NOW.” Tef Poe, the St. Louis rapper and Ferguson protest regular, has quotably insisted that BLM “ain’t your grandparents’ Civil Rights Movement.” Even in this slogan in favor of young blood, however, the generation of Diane Nash and Bayard Rustin qualifies as a blood relation whose legacy demands fresh but comparable styles of political devotion.

For all its urgency, BLM’s elevation of Baldwin would remain strategic, short on emotional magnetism, if his commentary on subjects pressing to the movement didn’t seem eloquently fitting. Yet his collected writing makes the curating of a BLM Baldwin as respectful as it is self-flattering. In broad strokes, the pro-BLM voice to be built from this writing seconds the movement in content and schools it in form. The Baldwin so assembled offers committed readers a compelling blend of confirmation and challenge, a mirror of shared social analysis offset by a not-just-stylistic question: namely, to paraphrase Ta-Nehisi Coates, Why don’t people write sentences like this anymore?

Read in tune with Black Lives Matter, Baldwin’s best-known essays and novels cast the physical precariousness of black American life, its disproportionate exposure to injury and murder, as white racism’s steady baseline. The “Negro’s past,” Baldwin maintains in “The Fire Next Time,” is a thing of hard-earned, precious beauty — and “of rope, fire, torture, castration, infanticide, rape,” of the constant, humiliating fear, “deep as the marrow of the bone,” of “death.” Like BLM, this Baldwin paints the red record of white terrorism as an obsession with breaking the black form, its erotic power above all. “A Black man has a prick, [therefore] they hack it off,” Baldwin cynically reasoned in dialogue with Audre Lorde. Sanctioning the secular materialism of a Coates, for whom the “particular, specific” black body is the final horizon of emancipation, Baldwin projects an electrically embodied post-Christian era, one in which the teary kiss and “protecting arm” of the lover outstrip any sacred blessing at the close of his autobiographical first novel, “Go Tell It on the Mountain” (1953).

Also like Black Lives Matter, this Baldwin sees the integrity of the black body menaced by a conspiracy between two outwardly opposed faces of white supremacy. The first of these faces is white innocence, redefined in the Norman Mailer-haunted essay “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy” as a willful offense and “the thing that most white people imagine that they can salvage from the storm of life.” The second face is the keeper and enforcer of this fantasy of deliverance, the white police. It’s a white cop who teaches Rufus Scott, the martyred jazz drummer at the hub of “Another Country” (1962), just “how to hate.” And Scott, the keeper of Harlem’s beat, collectively played by “hands, feet, tambourines, drums, pianos, laughter, curses, razor blades,” is a black everyman here as elsewhere. “Rare, indeed,” Baldwin testified in the essay “Fifth Avenue, Uptown,” “is the Harlem citizen, from the most circumspect church member to the most shiftless adolescent, who does not have a long tale to tell of police incompetence, injustice, or brutality.” As this reference to the cop-victimized church member hints, Baldwin upholds BLM in scorning the wager that freedom will follow respectability. The gay landmark “Giovanni’s Room” (1956) is only the least closeted statement of his faith that the flight from shame to safety — racial, sexual, and existential — is an immoral ugly Americanism. Seen through Baldwin’s eyes, the challenge of his time, and of BLM’s, is to accept that liberation can be won only “if you will not be ashamed, if you will only not play it safe.” This weighing of daring and principled self-transformation over settled demands for reform — denounced as pre-political self-indulgence by some in Baldwin’s day, and some in ours—is sympathetic music to BLM, a movement drawn to energized friendship circles above obedient membership lists.

All of these parallels have joined to make Baldwin the most-tweeted literary authority of Black Lives Matter. The blend of political prophecy and theatrical self-exposure in nearly all of his essays, regardless of their topic, indeed anticipates the very twenty-first-century job description of the freedom fighter/social media star. Yet Baldwin is also appreciated by movement voices for the fundamental un-tweetability of his prose at its most identifiable, for the long and gracefully overstuffed sentences, immersed in the syntax of two royal Jameses, King and Henry, that confirm his share of historical remoteness. Tweet this, the lavish Baldwin sentence seems to say, as in this stem-winder from “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” the sentimentally Oedipal 1949 essay that made Baldwin’s name on two sides of the Atlantic: “Sentimentality, the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion, is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel; the wet eyes of the sentimentalist betray his aversion to experience, his fear of life, his arid heart; and it is always, therefore, the signal of a secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty.” In the relatively few, firmly vernacular words of a tweet by a Brooklyn BLM supporter, Baldwin is due homage because such “sentences be a page long and still grammatically correct. That boy ice cold.”

On his own Twitter account, Coates has similarly celebrated Baldwin’s control of the more-than-140-character formula; and in “Between the World and Me”, he channels both the low page total and the lingering, spun-out phrasing of “The Fire Next Time,” one of the fullest short books in American literature. It’s no accident that Rankine chooses to integrate Baldwin into “Citizen” through a long, grammatically correct, and paradoxically languid quotation (here cut for length) describing a temptation to violence: “And there is no [black American] who has not felt, briefly or for long periods, with anguish sharp or dull, in varying degrees and to varying effect, simple, naked, and unanswerable hatred; who has not wanted to smash any white face he may encounter in a day, to violate [it], out of motives of the cruelest vengeance . . . ,” etc. Baldwin’s mushrooming commas and semicolons are a far cry from Citizen’s interspersed images and rapid jump cuts. But the inclusion of the former devices in Rankine’s work demonstrates the historical pedigree of her interest in the dilemma of black vengeance—a pedigree signaled in part by Baldwin’s distance from her economical formal repertoire. Baldwin’s selected opinions have made him a virtual contemporary of Black Lives Matter. His lush and unpragmatic style, by contrast, is a tool through which the felt pastness of a selective black past can be measured for present use.