Step in to the Denver, Colorado home of Landon Meier and a table full of bodiless heads greets you just past the front door. There’s a deceptively friendly Tyrion Lannister from the bloody “Game of Thrones” universe. He’s propped behind a tattooed, smiling Mike Tyson, who looks ready to accept your offer of candy while still perfectly capable of eating your children, like the real-life boxer once told an interviewer after a fight. Next to Iron Mike is an intense, slightly slack-jawed Walter White from “Breaking Bad” who can’t completely come out of the shadow of the massive crying baby mask behind it — the one that changed Meier’s life six years ago.

The supremely freaky crying baby mask made its initial pop culture splash in performance artist Jillian Mayer’s 2011 viral YouTube video “I Am Your Grandma.” When the mask appears onscreen, it’s hard not to rescind in horror, or as Meier observes: “It’s going to give somebody a mid-day nightmare.”

Read more Narratively: This Standup Comic Turned His Disability Into Comedy Gold

“I wanted to create a surreal experience for the innocent bystander who sees somebody wearing these masks,” Meier, 41, explains. “If for one moment I can make someone think something’s real, but something’s wrong, kind of an uncanny feeling, that’s artistically what I was trying to do.”

The success of the 63-second film sparked heavy viewership of Meier’s own YouTube video featuring an entire family inducing double-takes while sporting the baby heads at a Downtown Denver outdoor mall.

“Social media one hundred percent made my business,” Meier says sitting at his dining room table, supporting less-harrowing items like cups of coffee and bags of sour gummies. “I was on unemployment for two years, and right at the very tail end of it, overnight, ten people a day were emailing me” — all inquiring about the masks they saw in the videos. “It became a full-time job.”

Read more Narratively: The Guy Who Played the Red Power Ranger Killed His Roommate With a 30-Inch Sword

Primarily made of either latex or silicone, Meier’s “Hyperflesh” line of masks are most frequently inspired by topical, pop culture figures — “characters,” he says, “oddballs and people who might not be the most perfect.” When he unveiled a Charlie Sheen mask, it was so lifelike that the actor himself purchased it for Halloween. Then in 2013, Bryan Cranston, who portrayed Walter White on “Breaking Bad,” strolled through San Diego Comic-Con donning the Hyperflesh mask of his own likeness, interacting with superfans of the show, none the wiser to the fact that they’d just met its star.

“He was laughing his ass off,” says Meier, who was hanging out next to Cranston the entire time, himself in a Mike Tyson Hyperflesh mask. “The whole idea was that if you’re a celebrity, you can’t be on the [Comic-Con] floor because you’ll just be swarmed by people,” Meier remembers. “Well, either way we were swarmed by people because that’s the reaction you get out of these masks.”

Read more Narratively: When Someone Destroyed Our Pride Flags, Our Tiny Town Sprang into Action

Cranston, who was nice enough to hand out Hyperflesh business cards at Comic-Con, kept the mask on during his introduction to the “Breaking Bad” panel. After he removed the mask, his co-star Aaron Paul began making out with it. “It was one of the coolest experiences of my life,” Meier says.

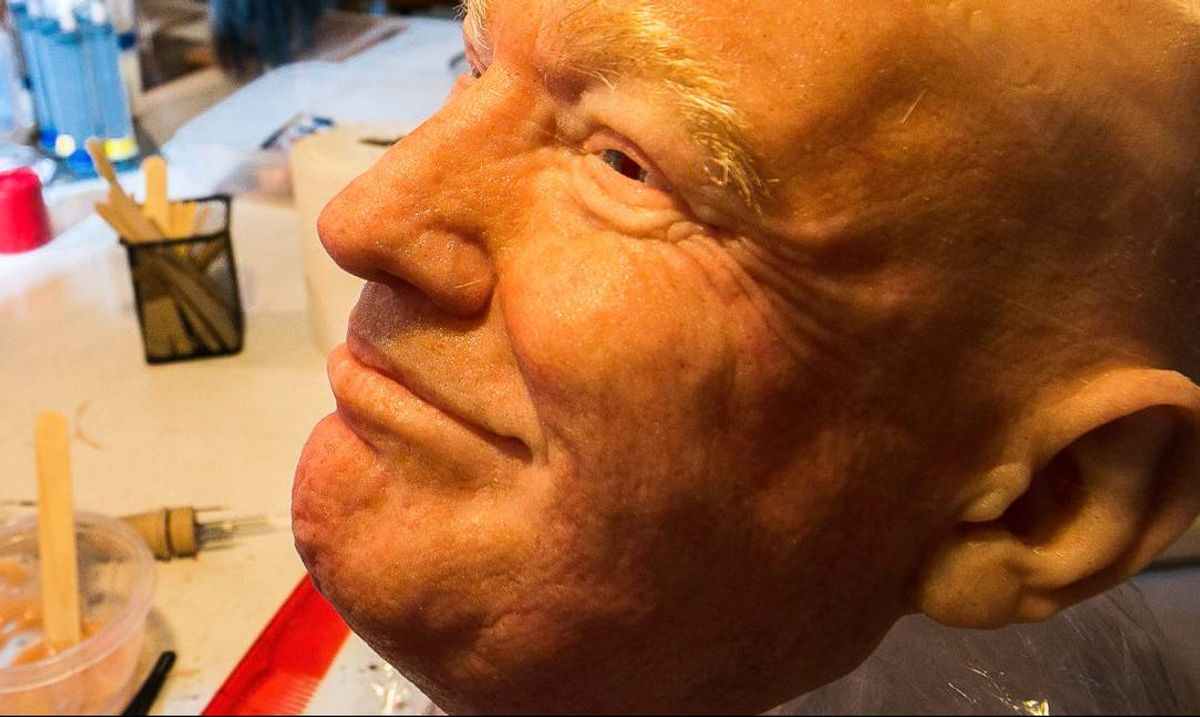

During the combative 2016 presidential campaign, Meier kicked his game up another notch. For the first time, utilizing ZBrush digital sculpting computer software to generate custom facial images in tandem with a 3-D printer, Meier unleashed a Hyperflesh line of political masks made of a more natural-looking silicone in spring 2016: hyper-realistic, humorous homages to Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders.

Like the crying baby masks, these were dubbed “terrifying” and “creepy,” which delighted Meier. “I’ll take that all day long,” he says. “When I’m sculpting out a head I’m not thinking, is that disturbing? But it just ends up being so.”

This past year Meier fine-tuned his methods to generate an even more accurate-looking Trump mask. (He admits the mask from 2016 had a complexion that was too dark, even by human Trump standards.) Meier also made sure Trump had a friend with an equally awful coif to play with in Kim Jong-un, while a sneering Vladimir Putin joined in the fun — though, according to Meier, he “clearly is the adult of the three.”

Meier debuted his latest merry band of masks in April at Monsterpalooza — a film, makeup and special effects tradeshow — where a tall model portrayed a gold chain-clad Putin towering over Trump and Kim, each wearing t-shirts depicting atomic bomb explosions. Meier’s intention was to portray the unimposing pair as “spoiled brats” while suggesting Putin oversees the actions of the other two evil, dim-witted leaders.

An associate of the Stan Winston School of Character Arts filmed a video of the three masked models dancing to Bruno Mars’s hit song “Uptown Funk.” The video garnered 67 million views, and Meier went to work again, fulfilling order requests.

“I’m on mark to sell maybe fifty-plus this year,” Meier says, with Trump easily serving as bestseller.

Given all the exposure Meier’s masks have received, that sales figure might resonate as underwhelming. But after the masks’ coming out party at Monsterpalooza, Meier would only commit to making one after securing a guaranteed $4,500 from a buyer – an asking price that is now another $1,000 higher for the Trump mask.

Meier resents the notion that his prices are too exorbitant and is upset about the great attention paid to his rates in the media. He says busts or statues of popular movie characters like Predator, Alien or Frankenstein, which can also be seen at events like Monsterpalooza, will regularly sell at higher prices than his masks, but he feels his work and rates are subject to backlash because “people think it’s just a Halloween mask” that should cost twenty bucks. He says his carefully engineered masks are much more than a novelty.

“This is sculpture; these are fine pieces of art,” he says. “You should display this stuff, maybe not on your fireplace mantle, but in your office or someplace like that. A lot of work goes into these.”

In one corner of his basement studio, Meier has a desk with a tremendous monitor. In the beginning stages of his mask-making process, he fires up the ZBrush program, which displays a three-dimensional, gray-colored ball meant to resemble fresh clay. Meier utilizes the cursor to pull, pinch and carve into the ball, making a face emerge from the virtual clay in seconds. He can superimpose photos downloaded from the internet over the graphic he created with the software to guarantee the authenticity of the shape of his subjects’ heads. The software also allows him to painstakingly strive for incredible accuracy in all the masks’ fine details, right down to the wrinkles and the rosacea.

It takes about a week’s worth of computer time to get the face imaging just right. When that’s done, his 3-D printer goes to work, zipping thin streams of molten plastic in all directions, generating a face identical to the one on his monitor. Then, Meier uses the 3-D printer’s output to create a traditional mask mold, painting the flesh-toned silicone throughout the inside, laying specifically pigmented and textured portions of the material to mirror particular areas of the face. After 48 hours, the silicone is cured and ready for removal.

For each individual mask it takes another week for Meier to finish the more hands-on, labor-intensive steps, including painting and implanting hair – synthetic extensions like those purchased at a salon. Meier injects the strands into the heads using multi-pronged felting needles, though usually the eyebrows have to be sewn through, one hair at a time with a pin vise because he is quick to observe incredibly fine details in his subjects’ brows. To get the hair to rest on the head, he warms the locks with a flat iron, and they magically fold in place.

Working on a completely bald Trump head one recent weekend, Meier carefully applies extra silicone to fill in what looks like a brain surgery scar, but is just a lengthy divot leftover from the molding process. Meier says the seam would probably go completely unnoticed by his client — a well-regarded Hollywood director whom Meier didn’t wish to name — once the hair is applied. However, Meier calls himself a “paranoid perfectionist,” which is the main reason he hasn’t hired any help yet, though his girlfriend of nearly four years has been trained to craft the crying baby heads.

“I’ve always been ‘the artist,’” says Meier. “The first badass drawing I did was of Winnie the Pooh; I was like four years old, but it was pretty damn good.” He says if he didn’t become a professional artist, he would have been letting everyone down, failing to fulfill his destiny. He painted through his teens, his friends and family nurturing his talent through approbation. He loved the work of surrealists like Salvador Dalí and Francis Bacon, but by college preferred the “more fulfilling experience” of sculpting. With painting, Meier says, “You’re creating the idea of a three-dimensional space.” But in sculpting, “You’re physically creating in a three-dimensional world.”

After earning a fine arts degree in college, he toiled as a loan officer and pizza delivery boy throughout the early 2000s, while learning the trade of mask making from a couple of local manufacturers — the Reinke Brothers of Littleton and the Distortions crew of Greeley. After a picture framing business he worked for went out of business, he lived primarily off unemployment and manufactured a crying baby mask every once in a while, until that viral video by Jillian Mayer changed everything.

The Trump, Putin, and Kim masks, a creative leap for him, have now become his “cash cow.” But Meier also says he feels “kind of stuck just making masks” these days. “As an artist I want to express myself more,” he says. “I want to move into the realm of fine arts. I’ve got some ideas for large sculptures or maybe even a gallery installation.”

After a contemplative pause, he adds: “Hopefully the masks lead to bigger and better things. I’m a big dreamer. I’ve even got an idea for a movie — but who doesn’t, right?”

Shares