I’ve heard dozens of people over the pre-Fourth of July weekend make the comment that the founders must be rolling over in their graves at the spectacle of Donald Trump as president of the United States. Maybe they are, but not because they are shocked at the spectacle of an incompetent leader. After all, at the time Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence they were dealing with the Donald Trump of his day: Mad King George. In fact, they pretty much wrote the Constitution with him in mind. And he wasn’t the only one. There had been many European monarchs who were off their rockers, and much of the Enlightenment was informed by that fact.

Thomas Jefferson's “Original Rough Draught" of Declaration of Independence (with revisions by John Adams & Benjamin Franklin): pic.twitter.com/Csv0pbLSIm

— Michael Beschloss (@BeschlossDC) July 3, 2017

This comparison to Trump isn’t an original thought, of course. Almost from the moment he took office people have been comparing him to the Mad King. Last February in the New Republic, in the wake of the president’s bizarre first press conference, Jacob Bacharach surveyed unhinged rulers of the past from Caligula on down and recalled the 1994 film “The Madness of King George,” in which William Pitt, the prime minister, said:

We consider ourselves blessed in our constitution. We tell ourselves our Parliament is the envy of the world. But we live in the health and well-being of the sovereign as much as any vizier does the Sultan.

But the Trump administration isn’t just evoking images of the Mad King on this Fourth of July. As it happens, one of the more interesting dramas of recent years about the revolutionary period is the AMC series “Turn: Washington’s Spies,” about the famous Culper spy ring. It’s a harrowing story of daring and bravery that I enjoyed very much when I was a kid, and it served as my introduction to the Revolutionary War.

This version is sexed up for our time and, according to Revolutionary War buffs who have followed the show closely, some of the historical details are way off. For instance, every historical drama has to have a “24”-style torturing psycho, and this one decided to sully the good name of a British officer named John Graves Simcoe, the Culper ring’s nemesis. By all reliable accounts, the real Simcoe was an honorable soldier who went on to become the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada. Overall, however, “Turn” gets pretty good marks for authenticity.

I have noticed, however, that since Trump’s election the theme of loyalty and betrayal has more resonance to current politics than it had before. You see, the Culper ring was responsible for uncovering information about one of the most infamous episodes in American history, the treason of Benedict Arnold, a homegrown war hero. “Turn” adds in some love-triangle stuff involving Arnold and a British spy named Major John André that isn’t historical. But the real-life spy ring was instrumental in repelling Arnold’s first action as a British turncoat (a planned surrender of West Point) based upon some intercepted correspondence between the general and the British agent. When it was foiled, Arnold defected to the Crown and led many raids and battles against the Continental Army.

The name Benedict Arnold remains synonymous with the word “traitor” in America. I’m sure once they learn the story, kids still call friends by that name when they feel betrayed. He is the most notorious turncoat in our history. If you discount the Civil War, in which dozens of U.S. Army generals took the other side, he’s the only general who ever defected. And his reasons were pretty parochial.

Arnold was a brave soldier who was gravely wounded in battle and was beloved by his troops. But he had a prickly personality and was a man his fellow officers found to be a pain in the neck. He was terrible at politics and got caught in a number of shadowy financial schemes trying to impress his 18-year-old loyalist fiancée. After that he survived a court martial but became so resentful and embittered about it that it drove him into the arms of the British.

Before he went over to the other side, Arnold wrote a series of hysterical letters to George Washington, in one of which he declared:

Having made every sacrifice of fortune and blood, and become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet the ungrateful returns I have received of my countrymen, but as Congress have stamped ingratitude as a current coin I must take it.

He needed money, and that was part of it. But Arnold also felt that his country had betrayed him, which he rationalized as a justification for betraying his country right back.

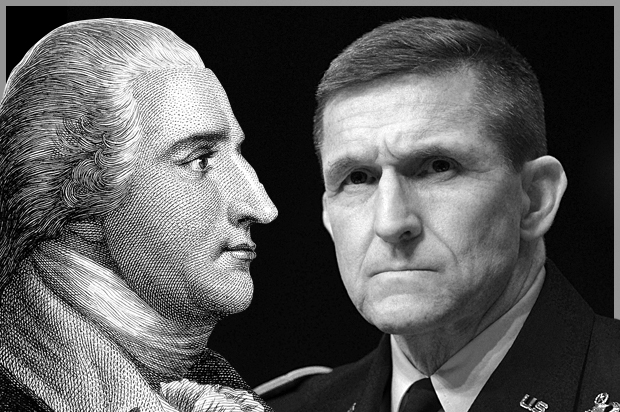

As I watched the show and thought back to my school days and the stories I read about Arnold’s treachery, I couldn’t help but think of former Gen. Michael Flynn. By all accounts, Flynn was extremely resentful at being fired by President Barack Obama as head of the Defense Intelligence Agency, and nursed grudges against his rivals in the other intelligence agencies. He had been popular with his own troops but others in the military came to mistrust him and considered him a little unhinged.

After Flynn left the government, at first he simply parlayed his insider knowledge into big dollars as a foreign agent lobbying for Russia and Turkey. When he met up with Donald Trump, Flynn evidently found an outlet for his resentment against his former rivals. We don’t yet know whether this actually led him to work with a foreign government to subvert his own. There are certainly allegations that he may have tried. Today Flynn finds himself in the crosshairs of a government investigation into both his financial dealings and his political activities.

One can easily imagine him testifying before Congress and saying, “I little expected to meet the ungrateful returns I have received of my countrymen, but as Congress have stamped ingratitude as a current coin I must take it!”

Karl Marx’s old adage holds that history repeats itself, first as tragedy and then as farce. I’m not sure which one we’re witnessing at the moment. Let’s just say that there are echoes of another leader’s derangement and a different general’s obsessions in all this. America has been dealing with such human peculiarities from the beginning. The good news is that we seem to have a knack for surviving them.