The bridge, upon which a lot of history has passed, still stands. Renovated, but with some of the original paving slabs that once echoed the hobnailed boots of Japan’s Imperial army.

It was on this bridge that an incident took place, 80 years ago, that some historians now believe may have been the first shots of WWII.

Time to correct the Eurocentric world view?

Certainly, the forces that were unleashed — including the deliberate targeting of civilians and urban areas, as well as the twisted beliefs in ethnic superiority — were characteristics of the global conflagration that up until now was entirely deemed to have started in 1939.

It is legitimate to suggest that the incident that sparked the conflict that became World War II occurred not in Poland in 1939 but in China, near this eleven-arched bridge on the outskirts of Beijing in July 1937.

Let’s look at the undisputed facts: Japan occupied Manchuria in 1931. A wider invasion began in 1937 and, by the time Japan surrendered in 1945, between 13 and 20 million Chinese people had died. Refugees trying to flee the fighting numbered 100 million.

The incident, during the night of July 7-8, 1937, was a bloody skirmish between Chinese and Japanese troops on and near the bridge.

It was initially ignited by reports of a missing Japanese soldier who was later found. In the event, this one incident sparked a sweeping Japanese invasion of China, and became known as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident.

The Anti-Fascist War

The conflict is referred to in China as the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45) and the Anti-Fascist War.

Japan’s expansionist policy of the 1930s, driven by the military, was to set up what it called the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

A sphere. Such a mundane, seemingly innocuous word. To commemorate the attack properly, The Museum of the War of the Chinese People’s Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, located inside the Wanping Fortress, near the bridge, set up the Great Victory and Historical Contribution exhibition.

The museum was opened on July 7, 1987 on the incident’s 50th anniversary. It shows the consequences of trying to establish such a “sphere.”

Its air-conditioned halls display the relics of war: rusty rifles, machine guns, tattered tunics. From the walls hang grainy black and white pictures that bear testimony to the brutality inflicted upon Chinese civilians.

More than 2,800 artifacts and 1,000 pictures are on display. They assault the senses. A spiked metal cage to torture captives, images showing heads mounted on stakes and the remains of a raped woman are painful to look at.

They are a juddering reminder that before Britain’s lonely battle for survival in May 1940, China stood alone.

The Kuomintang and the Communists

But hold on. Was it not the Kuomintang, the nationalists, who largely engaged the Japanese? After all, the Communists, who eventually defeated the Kuomintang in 1949, were in disarray in 1937.

Didn’t Mao Zedong tell Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka in Beijing in 1972, when diplomatic relations were restored between China and Japan, that if it hadn’t been for the Japanese, the Communists would never have taken power as the invasion gave them time to regroup under an umbrella of resistance to Japan?

The museum, not surprisingly, plays down this aspect. Some of the captions do mention the Kuomintang. Yet, one is left with the impression that the Communists were largely responsible for fighting, or at least organizing, the resistance to the Japanese.

The war ended in Europe in May 1945 and Japan surrendered in August. The official Japanese surrender was received on the USS Missouri on September 2 and the Chinese delegation on the ship announced a three-day holiday from September 3 to mark victory over Japan.

The Chinese theater is only now beginning to be appreciated as a factor in tying down Japanese troops. But the Communists were also none too keen on discussing the war in case it gave credence to the Kuomintang.

A new era

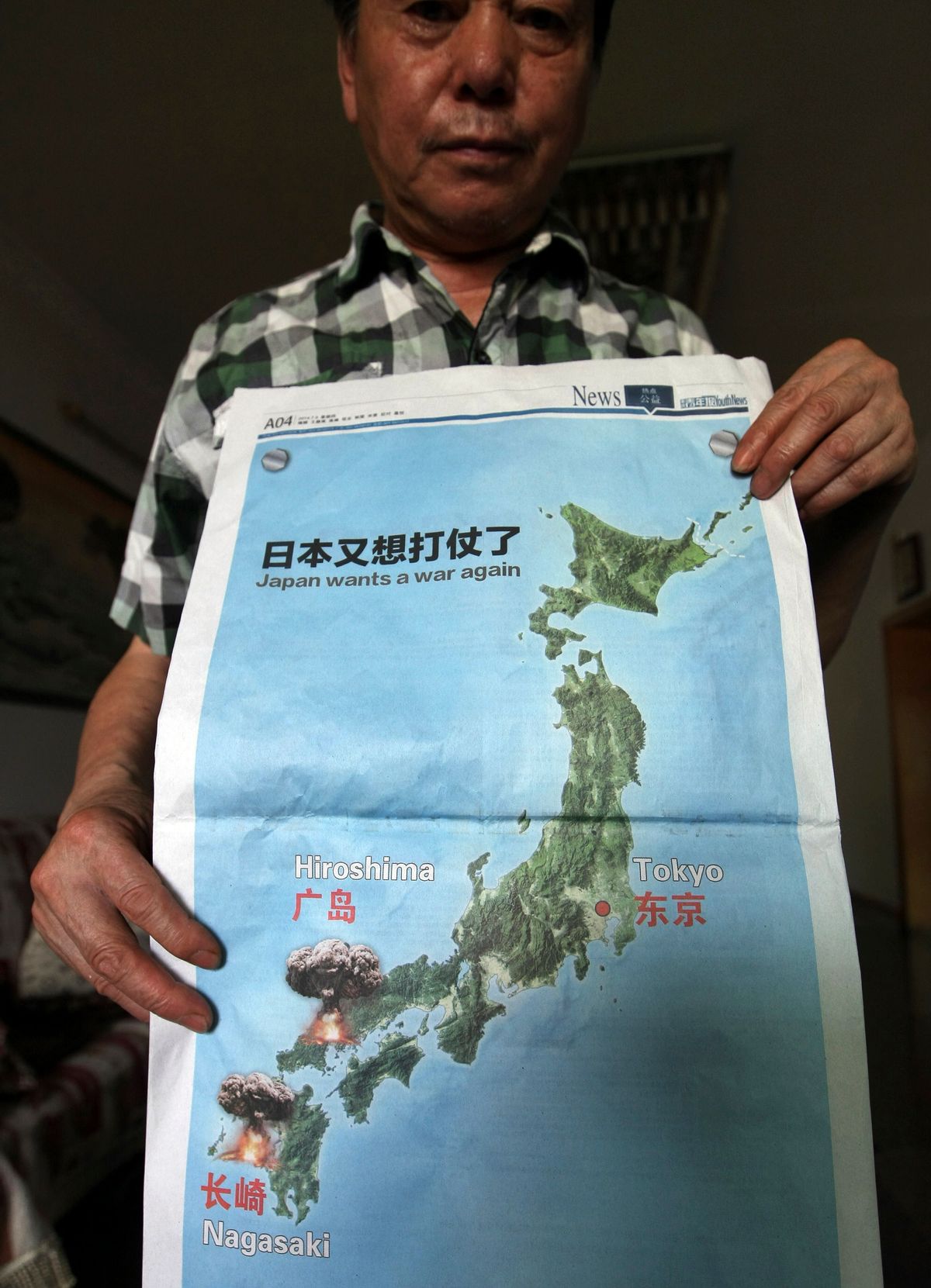

That has changed. A more assertive Beijing feels it can bolster its reputation by establishing direct lines between resistance to Japan, its legitimacy and its stance against Japan in maritime disputes.

But if the past is another country, then in China that country is Japan. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is viewed as insincere in Beijing for his comments regarding Japan’s wartime actions.

Of all the ironies, it is Japan, a country where the apology is an art form, that should find itself criticized over its inability to convince.

The world history that occurred on that bridge underplays the Japanese Imperial army’s atrocities or indeed the brutality of the Cultural Revolution. It still needs further sorting out.

Shares