Early discos and punk clubs often coexisted in the same downtown neighborhoods and occupied similar kinds of spaces: lofts, storefronts, basements, and bars. It also wasn’t uncommon to hear disco, glam rock, and punk music on the same night, in the same venue. Club 82, for instance, alternately functioned as a drag club, a disco, and a rock venue that hosted the New York Dolls, Television, Wayne County, The Stillettoes, and Clem Burke’s pre-Blondie band, Sweet Revenge (who used to play a punky song titled “Fuck the World”). “I would say that’s where Blondie absorbed the whole disco thing,” Burke said, “because the music that they would play at Club 82 in between sets would be like ‘Rock the Boat’ or ‘Shame, Shame, Shame,’ and all this dance music. The whole disco scene was going on simultaneously to the punk scene.”

Peter Crowley, the booking agent for Max’s Kansas City during the punk era, recalled the goings-on at Mother’s (a gay bar that paid the bills by hosting underground rock shows in the mid-1970s). He told me that the jukebox at Mother’s often played disco songs, and it wasn’t uncommon to see a gay waiter sashaying to the beat between live sets by Suicide, The Ramones, The Fast, or Blondie.

Mother’s was also right across the street from a popular disco named Galaxy 21. “That was an amazing disco,” The Fast’s Paul Zone said. “You would go there and it would be crazy fun wild people. It wasn’t that out of the ordinary for most of us to embrace that and to be a part of it.”

A November 10, 1974 event that helped establish Patti Smith as a major figure in the emerging punk scene took place at The Blue Hawaii Disco. Paul Zone captured that performance—part of her “Rock ’n’ Rimbaud” series—with an unlikely photo that included the raggedy singer and a glittering disco ball in the same frame. This is yet another reminder of punk and disco’s common roots in the social and geographic margins of downtown New York—though only one of these subcultures was praised by rock critics. Rolling Stone writer Peter Herbst admitted that disco was kept at an arm’s length by the magazine because its staff associated disco with those “outside of the rock and roll population that we belonged to personally”—you know—“blacks and gays and women.”

White male rock writers often turned a blind eye to disco’s subcultural leanings, or were outright hostile to the music and its fans. Many of these same critics helped popularize a macho, cartoonish version of punk that had little to do with the much more artsy, gay scene that originated downtown.

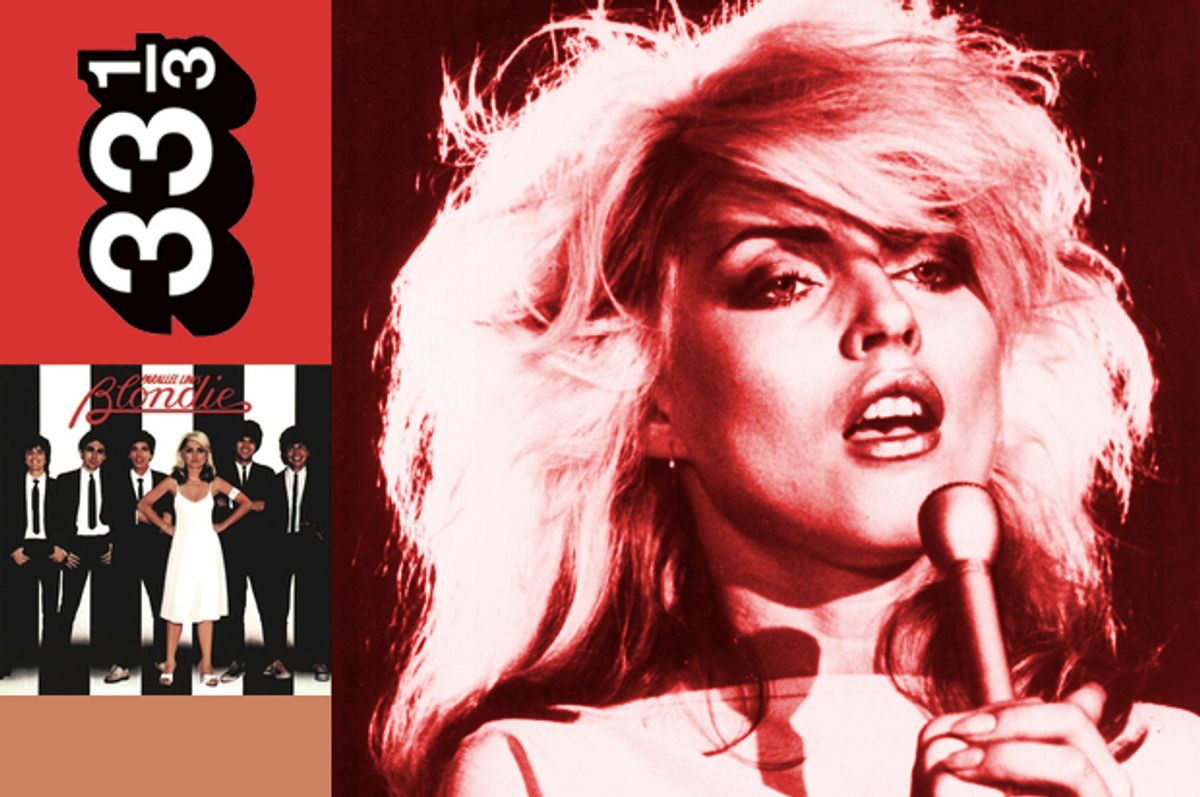

Blondie Stumbles Into Existence

When Debbie Harry quit The Stillettoes, she brought along drummer Billy O’Connor, bassist Fred Smith, and guitarist Chris Stein. The group initially rechristened themselves Angel and the Snakes, playing a couple shows at CBGB with two backup singers named Julie and Jackie.

When Angel and the Snakes morphed into Blondie and the Banzai Babies, the backup singers were replaced by Tish and Snookie Bellemo. This sister act later started their own band, Sic F*cks, and they also opened the punk fashion store Manic Panic (a brand best known for its hair dye).

“One thing about Debbie and Chris, as artists they were always evolving, and maybe they used people,” Clem Burke observed. “Not in a negative way, but in a delegated way, where they thought maybe, ‘Okay, we’re going to move on and maybe we’ll get a different energy from some other people.’ They were always in that process.” Performing as Blondie and the Banzai Babies, Harry and the Bellemo sisters wore a variety of campy outfits—from cavewoman clothes and 1950s party dresses to, of course, glitter. “Debbie decided we should be a disco dance band,” Snookie said. “She got us a job playing Brandy’s Too, an Upper East Side singles place, two long sets a night.”

The swinging singles crowd didn’t really notice the group’s unsavory lyrics in songs like “Funky Anus,” though the club’s patrons were thoroughly disturbed by the supporting act they brought along. “The Ramones came to open for us,” Tish recalled. “But they started out with ‘Sniffin’ Glue’ and the management asked them to leave.”

“Chris liked a lot of disco songs, and so did I,” Harry said. “We really did like covering those songs, like ‘Love to Love You Baby’ and ‘Disco Inferno,’ but it was also really funny to play that stuff because we were in the middle of this whole ‘I hate disco’ scene. It was fun to provoke people.”

“Heart of Glass” was one of the first songs Chris Stein wrote for Blondie in 1974, and it was included on their 1975 demo as “The Disco Song.” Gary Valentine recalled, “It was a joke, sort of. It was ironic—that’s the way I always took it—because it was just called just ‘The Disco Song.’” Blondie had largely abandoned this trifle until Parallel Lines producer Mike Chapman asked the band to play all their unrecorded songs during the album’s preproduction phase, in early 1978. When Chapman heard it, his Top 40 radar pinged. “I thought that track was the one that probably needed the most attention, because even though it was complete, it was wrong, and I knew that if we could get it right it might be a big hit,” Chapman said. “Anyway, we fooled around with the song, and after a couple of hours of very intensive work we had it sounding pretty much the way it sounds today.”

“The early version of ‘Heart of Glass,’ that arrangement had a more standard disco beat, with doubles on the hi-hats and so on,” Chris Stein said. “But Jimmy [Destri] had just bought a Roland drum machine and we were all really into Kraftwerk by the time we recorded it for Parallel Lines. The final version, to us, wasn’t really disco. We were thinking more along the lines of European electronic pop.”

“Back when it was called ‘The Disco Song,’” Harry recalled, “pretty much all I said was, ‘Once I had a love, it was a gas. Soon turned out, it was a pain in the ass.’ It didn’t quite work well, so that’s when we came up with the line, ‘Soon turned out, had a heart of glass.’” She fleshed out the lyrics, but kept one line with the word “ass” in it, much to the delight of juvenile radio listeners (like myself, who was eight at the time). That minor cuss word—along with Harry’s two-tone bleached ’do and punk ’tude—positioned Blondie as radical subversives, at least when compared to their pop star contemporaries.

“Heart of Glass” gave Blondie its first American number one hit in 1979, but in the group’s early days, they were barely keeping it together, musically. “Our hottest number was ‘Lady Marmalade,’” Harry said of that period. “We were a dance band, but to tell the truth we were so bad that to call us a garage band, to call us a band, was a great compliment. We were a gutter band—a sewer band is a closer description.”

Shares