This shift was partly due to the evolving social and moral values held by many Northern liberals and the subsequent cultural backlash that followed in much of the country. But “liberal” only turned into a snarl word after decades of right-wing rhetoric that painted Democratic politicians and liberal thinkers (i.e., college professors and journalists) as out-of-touch cultural elitists who knew nothing — and cared little — about “real America.”

Of course, the right’s effort to turn liberal into a dirty word was aided by many of the so-called liberal politicians of the late 20th century, who, rather than pushing back against the right’s rhetoric, hopelessly ran away from the label (just as one might expect of a spineless liberal elite).

And today, decades after becoming a pejorative that implies elitist snobbery, the term "liberal" is still used to great effect by the right. Indeed, Donald Trump seems to have perfected the liberal-bashing rhetoric that was introduced in the 1980s, and offensive portmanteaus like “libtard” have gained popularity in the Trump era. But it’s not only right-wingers who use "liberal" as a slur these days. In 2017, "liberal" is almost as much of an insult on the left as it is on the right — a theme that was recently broached by writer Nikil Saval in an essay for the the New York Times Magazine. Among leftists, Saval notes, the liberal is seen as a “weak-minded, market-friendly centrist, wonky and technocratic and condescending to the working class … pious about diversity but ready to abandon any belief at the slightest drop in poll numbers.”

At first it may seem that conservatives and leftists are criticizing liberals for opposite reasons: Right-wingers think that liberals are far-left ideologues, while actual leftists think that liberals lack core beliefs and are practically conservative. But the two critiques aren’t completely divergent; as Saval explains:

When it comes to diagnosing liberalism, both left and right focus on this same set of debilitating traits: arrogance, hypocrisy, pusillanimity, the insulated superiority of what, in 1969, a New York mayoral candidate called the ‘limousine liberal.’ In other words, the features they use to distinguish liberals aren’t policies so much as attitudes.

This isn’t entirely fair to critics on the left, who tend to focus more on policy differences and believe that the Democratic Party is far too centrist and technocratic (or, as many leftists would put it, “neoliberal”). One of the greatest disputes, for example, has been over health care, where progressives advocate single-payer universal coverage while liberals offer a sheepish defense of the patchwork system enacted under Obamacare.

Still, Saval makes a valid point in that both leftists and right-wingers are highly critical of the condescending and superior tone that many liberals exude, and thus share some affinities in their critiques. This was evident during the 2016 election campaign, when leftists criticized liberals for what writer Emmet Rensin called the “smug style” in an essay for Vox, which won some praise from conservatives. Since the election, leftists and conservatives have also seen eye to eye when it comes to denouncing liberals like Markos Moulitsas, the founder of liberal website Daily Kos, who gleefully cheered when it was reported earlier this year that people in red states would be disproportionately hurt by Trumpcare. “Be Happy for Coal Miners Losing Their Health Insurance,” declared Moulitsas on his blog. “They’re Getting Exactly What They Voted For.” In another instance, the liberal blogger earned bipartisan condemnation (so to speak) when he tweeted in response to the Trump administration denying North Carolina hurricane aid: “There's your reward for voting Republican, North Carolina.”

Liberals like Moulitsas have almost become caricatures of the smug and unsympathetic liberal elite that right-wingers have long depicted; it's as if liberals have gradually come to adopt the ridiculous qualities that Republicans have assigned to them over the years. Which brings us to an important point: Leftists haven’t suddenly jumped on the liberal-bashing bandwagon because it’s the hip thing to do in the age of Trump, but because many self-described liberals have become the obnoxious and out-of-touch liberal elite that conservatives have long claimed them to be, while simultaneously shifting toward the right on various economic issues. (To be fair, obviously the right doesn’t see it this way.) Saval touches on this in his Times Magazine essay, observing that to call someone a liberal today “is often to denounce him or her as having abandoned liberalism.”

“American liberalism was once associated with something far more robust, with immoderate presidents and spectacular waves of legislation,” notes Saval. “Today’s liberals stand accused of forsaking the clarity and ambition of even that flawed legacy.”

This is obviously where left- and right-wing critiques of liberalism part ways. Indeed, right-wingers tend to focus almost exclusively on cultural and social factors in their criticisms, for the very reason that their economic policies are even more favorable to the “elite” than the policies of the “liberal elite” they disparage, who at least pay lip service to addressing problems like inequality and inadequate health care.

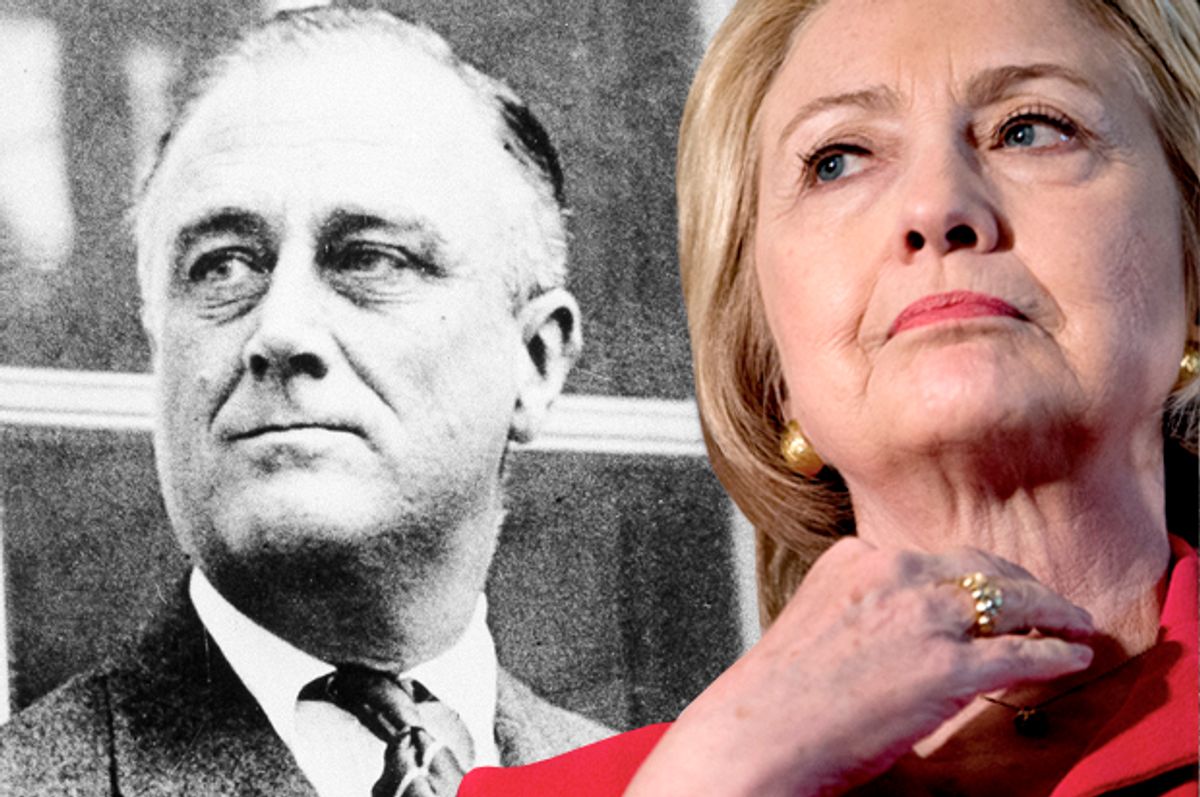

Left-wingers, on the other hand, see the cultural elitism of liberals as the manifestation of a larger problem — namely, the abandonment of class politics and radical thinking. To appreciate the difference between modern liberals and old-school liberals, one simply has to consider the sharp contrast in tone. In his famous Madison Square Garden speech, for example, FDR boldly declared:

We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob. Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me — and I welcome their hatred.

One would be hard-pressed to find any liberal today — other than someone like Bernie Sanders, who isn’t even considered a liberal in the contemporary sense — gallantly welcoming the hatred of organized money (after all, most Democratic politicians depend on big donors from the financial sector to fund their campaigns).

In response to the left-wing calls for class politics, liberals have frequently argued that leftists have an unhealthy “obsession” with economic issues, and that they disregard social issues like LGBTQ rights or women’s reproductive rights. Some liberals have even implied — absurdly — that left-wingers are closet cultural reactionaries. It was sometimes claimed during the 2016 primary campaign that progressives who favored Sanders didn’t like Hillary Clinton because of her gender, rather than her politics. But this kind of deflection simply reinforces the leftist critique of liberals, who, as Saval puts it (in summarizing the left’s perspective), “shroud an ambiguous, even reactionary agenda under a superficial commitment to social justice and moderate, incremental change.”

At the end of the day, liberals and leftists agree on a lot more than they disagree, and thus one might look at this internal strife as unhelpful and even destructive — especially when Donald Trump is in the White House and Republicans control both houses of Congress. But left-wing critiques of liberalism have only grown more urgent and necessary in the age of Trump, as it is the failures of liberalism that led us here in the first place.

Shares