If you lived through the 1930s and 1940s and had an interest in the world around you, you may have been aware that political, military, and media leaders used elements of drama and social psychology in the course of World War II. Many still remembered the devastating toll taken by World War I, and governments sought the most effective means of shaping emotions and opinions in this new conflict. Leaders orchestrated and shaped what was an ongoing, evolving history, creating a theatrical framework on both the home front and the front lines by applying elements of drama and new technologies that formed a consensual reality, a reality that fueled a media and entertainment industry that in turn—sometimes subtly, sometimes loudly—manipulated and maintained the illusions within and surrounding the war. All sides employed a variety of theatrical devices, each determined to ensure a hit. As in the theater, they competed with one another to make an impression, to secure and hold the audience’s interest, to arouse desire, and to provoke a response.

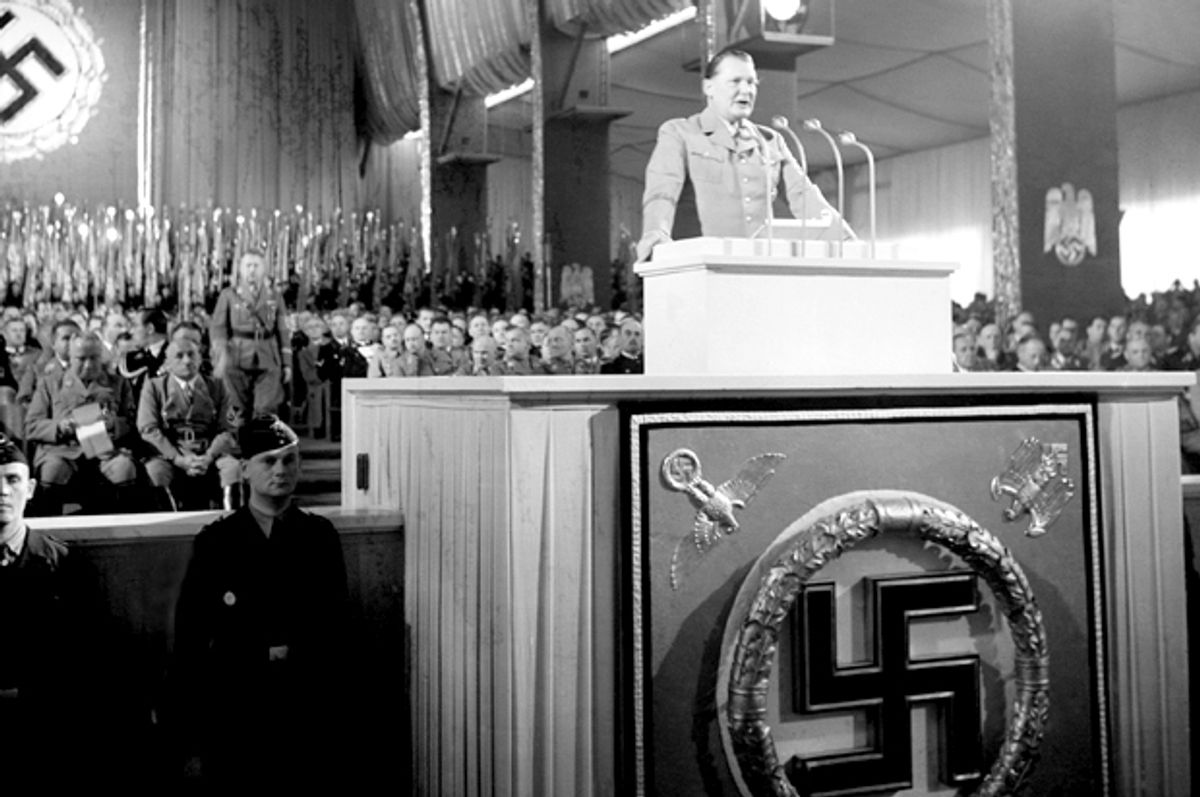

From the National Socialist blueprint — the Hitler script that was "Mein Kampf" and the elaborate, extravagantly staged Nazi performances at the Nuremberg rallies — to stirring British oratory and radio propaganda, to Roosevelt’s outmaneuvering of the isolationists on the home front, dramaturgy played a vital role in an event of global consequence.

In their influential work on symbolic interaction, Michael Overington and Iain Mangham document that the parallels between theater and warfare are unmistakable and of vital importance, so that under the direction of political leaders, the rigorous application of theatrical devices created a war-entertainment machine in America and Europe that took on a life of its own.

The broader notion that life and theater resemble one another is by no means just a twentieth- or twenty-first century one; it can be traced back to the dramatic unities of Aristotle and Shakespeare. But in WWII, this dramatic perspective took a new form, and leaders elevated spin to achieve their ends. Media was integrated with politics, spinning a tapestry the world had not yet seen.

In terms of history, drama was used to service this spin, to build a workers’ or citizens’ army, to obtain arms, to inspire fighting courage, for land and ideals, for a new society; for a Motherland forged in the Great Patriotic War; a Fatherland built on a utopian platform of world domination.

The freedoms built into America’s arsenal for democracy, the spirit of Avalon carried by the Commonwealth, the collective reforms in the USSR, the National Socialist German Workers Party, were led by master dramatists.

Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler, and Joseph Stalin functioned, as it were, as theatrical entrepreneurs, writer-directors who wrote, enacted, and implemented their own script. Hitler’s grand drama for his Third Reich began in the early 1930s. His intuitive understanding of staging and theatrics helped capture an entire nation. For the British, a meticulously realized theatrical structure was used to convince a country, alone against Hitler, of the need and, crucially, of their ability to fight and win an ultimate struggle. In the United States, where both cultural tradition and political pressure were urging Americans to remain firmly backstage, the act of engagement was a high priority for those who needed, by chance or circumstance, to be on the marquee.

Stalin’s rise was more brutal and less dramatic. He had to apply propaganda to establish his image in the eyes of the public. He had cities named after him; history books were rewritten presenting him as a leader playing a prominent role in the revolution of the Soviet Union and building him to the status of a mythological legend. Controlling media, he had his name included in the Soviet national anthem. Propaganda could build his revolution, but only if the masses rallied behind one another, transforming the message produced by his media machine into reality.

* * *

Erwin Goffman, a pioneer of impression management, argued that war, viewed in terms of a theatrical production, demonstrates that reality is or at least can be a reflection of dramatic intrusion. In other words, during wartime, life imitates art in dramatic ways. On all sides at all times during the war, strenuous efforts were made to provoke an emotional response and reaction from the audience. It was a time of costume and conflict, set and soliloquy, music and march, all this underscoring that war, while horribly real, could also be seen as a vast, epic drama, one created to enable populations to accept and cope with a terrifying reality.

As in a wartime film about adventurous aviators or a heroic king on the fields of Agincourt, a theatrical framework allowed political and military leaders to be supported by the entertainment and communications media, to structure the events of the war within accepted and understood dramatic conventions. Each sought to harness their own and the collective national energy to uplift and sustain the morale of their people—and also to chasten, even silence, critics.

* * *

In this war, had you been a general, part of your training would have been to learn to master both tactical skills and, more importantly, strategic ones, to manipulate and guide the behavior of your cast members, soldiers and civilians, in a manner that undermined or rewrote the enemy’s script, that enacted their own and used it to advance their cause.

If you had been a foot soldier on the front lines, you would have performed in uniform and played a highly risky but decisive role in a drama that demanded an emotional response from its audience back home.

If you were trapped with the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front in France, you may have been dramatically rescued by the Royal Daffodil or the Bluebird of Chelsea, part of a courageous armada of small fishing craft, steamers, and ferries that took you back to England during the evacuation of Dunkirk and been one of the men who made it back home. You would have participated in what is often celebrated by the Brits, and called the Miracle of Dunkirk, with incalculable misfortune for the German forces.

In one of the stranger twists of World War II, Hitler’s armored units, seemingly on the verge of a stunning victory, suddenly halted their advance on Dunkirk. According to some accounts, Hermann Göring wanted to take a share of the spotlight and impress Hitler and boasted that his Luftwaffe alone could destroy the trapped troops by attacking from the air. But weather interceded.

The British could hardly believe their luck.

* * *

Göring’s planes were hampered by cloudy weather and then struck by British pilots flying their new Spitfires, buying time for the troops waiting on the beach and at Dunkirk harbor. After a two-day wait, realizing that Göring couldn’t live up to his plan so easily, Hitler ordered his armored columns to move on Dunkirk, but by this time, nearly the entire British Expeditionary Force had escaped by sea, knowing that someday, somewhere, they would fight Hitler again.

Had you been part of Operation Fortitude, a crucial misdirection strategy staged in parallel with the 1944 D-Day invasion, you would have been an actor taking part in an elaborate deception, complete with sets that were constructed with make-believe equipment. Thousands of inflated rubber tanks and landing craft, dummy airfields, and a mass of decoy lighting were placed at diversionary departure points. This was pure theater. Perhaps you would have added a public presence as you and General George S. Patton made appearances for bogus daily inspections. The Allies depended on Berlin to conduct aerial surveillance, and Hitler was convinced the plan was authentic, that Patton would indeed lead the invasion, landing at Calais. The deception worked. The invasion was in fact directed by Dwight Eisenhower and the landings were staged over two hundred miles away.

If you had crossed the English Channel and fought on the beaches of Normandy, you would have been part of a mighty road company with a cast of thousands. Thirty-eight convoys of 745 ships, with four thousand craft, landed 185,000 of your fellow soldiers and twenty thousand vehicles in three days. One thousand aircraft dropped another eighteen thousand paratroopers. Thousands of trucks and tanks with tons of supplies landed on the bloodstained beaches of Omaha, Utah, Juno, Sword, and Gold. This was an impersonal striking assault of force, and in the havoc of man and machine, a correspondent named Ernie Pyle wrote about horror, bravery, and sadness, impacting readers in a different way. Far more intimate than patriotic victories. If you had been along with Ernie on those beaches, you would have been witness to a personal and heartbreaking commentary that you might never forget: “It was a lovely day for a stroll.”

If you had been Jewish and lived in Europe, in all probability you would have gone to a concentration camp. If you were among the “lucky” ones, you might have ended up in Terezín, a place promoted as “Hitler’s gift to the Jews,” where you would unwittingly perform a part in an international performance. In return for your safety, you, along with the chosen few of Europe’s Jewry—among them artists and musicians, veterans of WWI, aristocrats and statesmen, and those who had distinguished themselves as lawyers, professors, and doctors—would have turned over your home, any works of art, and other assets in your possession. For this you would have found for yourself and your family a home, a safe haven in which to sit out the war. Arriving in your finest livery, with the expectation of comfortable, not to say luxurious, living standards, complete with a spa, you were confronted with the shocking reality. Conditions were appalling and you had merely secured for yourself a temporary stay at a transition camp from which you would, in all likelihood, eventually be transported to a work and extermination camp in the east: Auschwitz-Birkenau. If you had not already been shipped out by this stage, you would have witnessed an international inspection, conducted by the International Red Cross, to promote world opinion that the German soul was indeed deeply compassionate. In the course of the preceding days and weeks the camp had been carefully refurbished and beautified, becoming a Potemkin village where the Nazis staged a spin scam of spectacular proportions and temporary success.

If you were a music-loving child at Terezín at this time, you might have been chosen to take part in a children’s opera, one that was joyfully performed for the occasion. But afterward you would have been sent on a transport on the railway line extended for this purpose, freighted without hope, to the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

If you were a patriotic German living in the Fatherland, you may have been awestruck by the cathedral of lights at the Nuremberg rallies, at the torchlight parades and Thingplätze, capacious arenas constructed to stage events that embodied Teutonic culture, productions that climaxed with a representation of the führer descending as your god on a dramatic device, an Aryan deus ex machina. Had you been at a particular Munich performance, you might have been so engaged as to be one of the three hundred thousand inspired to join the Nazi Party the next day.

Had you been a general or German statesman at Wannsee, a stunning lakeside setting near Berlin, you would have watched Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich, architect of the Holocaust, inaugurating the plans for the Final Solution, and then afterward you might have refreshed yourself without a care, enjoying the leisurely activities of the weekend.

There again, you may have been in Washington, and enlisted in Roosevelt’s platoon of poets, headed by laureate Archibald MacLeish, joining one of the alphabet of organizations that helped to script the war effort.

In the Soviet Union, you may have fought along with General Georgy Zhukov, who reached heroic status culminating in the Battle of Berlin.

Or back in London, you might have participated in one of Churchill’s brilliant “black” propaganda productions at Electra House where bogus radio stations transmitted broadcasts to Germany in perfect German, soap operas and concerts, while disseminating news, real and invented.

On the bombed-out home front in London, you would have heard Vera Lynn trilling “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square” and “I’ll Be Seeing You,” or Gracie Fields belting out “There’ll Always Be an England,” as you waited for the lights to go on again all over the world. You would have heard music in the background taking you to another place, a hopeful time. You may have wondered, Is this not the stuff of drama?

As a witness to history unfolding before your eyes, you would have seen the shaping of World War II in dramatic terms to fit your country’s needs for national survival and military dominance.

You might also have taken a part as a narrator. If you had been a correspondent embedded in World War II, for instance, you would have used radio, newsreels, and print to report from up close and personal an evolving drama to a distant audience back home. You would have been part of a company of correspondents, an interpreter of a war, a player in a theatrical event that was controlled partly by the producers of the play. In the theater of national and international politics, sociologist Peter Hall writes, “No issue really develops without some staging around a dramatic event.”

* * *

Governments used oratory and entertainment to establish a framework that would support their respective wartime finales both in the theater of warfare and the theater surrounding and supporting this war, to inspire the home front audience. All sides needed this painstakingly constructed framework for the war.

Politics and propaganda are well-suited—in fact, intimate—companions. “In Wartime,” Winston Churchill told Franklin Roosevelt, “truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.” This particular war involved “tangle within tangle, conflict within conflict, plot and counter plot, ruse and treachery, cross and double cross, true agent, false agent, double agent, gold and steel, the bomb, the dagger, costume and deception, and the firing party interwoven in many a texture so intricate as to be incredible and yet true.”

It cannot be denied that war resembles theater. It cannot be denied that propaganda, in the various strands of the media, influences and shapes actual events and real conflicts. Each member of the audience must come to see that any given war can be better understood by considering the theatricality, the artifice, and the underlying truths as the drama unfolds.

One politician who discussed the connection between propaganda, politics, and theater was Edmund Burke, the eighteenth-century Irish statesman and political theorist. Born in Dublin, after moving to London he served as a member of Parliament, and came to see the stage as a powerful medium for interaction between manners and attitudes, and as a mirror of contemporary society. The stage was not only a reflection of life, but also a performance of life itself. Burke believed that drama was an education for the political statesman: politicians should analyze and treat men in much the same way as a dramatist does.

Central to this belief was the idea that the stage provided an insight into the motives of human beings in political situations. The stage could actually teach political actors how to make use of men and situations imaginatively. Great statesmen often knew the history of the stage and were well versed in all its techniques.

The war had many inherently theatrical aspects, including masterful mise en scène by the leaders, and propaganda was only one aspect of the production. The huge audiences for radio, motion pictures, and print media, as well as radical innovations in applicable technology, made this a very different war on the home front and the front lines.

The connection between theater and war is immediately evident in what is often a shared vocabulary: the war took place in the European theater and the Pacific theater; etymologically, “troupe” and “troops” are the same word; a successful show is a hit. But of course the parallels run much deeper, including seven fundamental categories:

- Theater is a structure for ideas. War is a structure for ideology.

- In theater, actors play characters. In war, people “play” soldiers.

- Theater is performance. War is performance.

- Theater is live. War is live.

- Theater involves a scripted play. War follows a staging plan.

- Theater uses props and costumes. War uses weapons and uniforms.

- Theater has a director, a play with conflict, and an audience. War has a general, a script with conflict, and an audience.

* * *

Four leaders scripted the production in the European Theater of War. Each had his distinctive personality and little tolerance for interference. Franklin Roosevelt, hiding his steel leg braces worn since childhood, cloaked his masterful temperament in an amicable manner. Winston Churchill was much more tenacious, short, round, rosy, a mighty man in the trenches, a mighty talker, whose eloquent speech lisped in private conversation but knew no hesitation before a public or parliament in the ringing rhythms of Milton and the King James Bible. Adolf Hitler, dogmatic, ruthless, his character etched by ambition, feeling anchored in stone, and a persona framed by pose and posture, had little appeal except a rare jig, or a fondness for pretty ladies and well-behaved children, yet he proved an electrifyingly charismatic orator. And Joseph Stalin, the man of steel from Georgia, shrewd and silent, a master of secret service and intelligence, often quiet, but an expert manipulator achieving his grand ambition for Soviet society.

Such differences were not strange for leaders who did not come to power by accident. They had forced their way to the top because they were rulers by will and temperament, reaching their eminence, truly foreboding in responsibility, from such different backgrounds and such different processes. Two of the representatives of democracies had aristocratic heritage. Churchill liked to think of himself as half American, but he was English in every fiber of this being and every turn of thought. Hitler, while aspiring to some artistic appreciation, fell short from the canvas, born in modest surroundings, a failed artist and hollow bohemian who became a ruthless street fighter led by fanatical instinct. His intellect had no scholarly timbre.

In their lives and thought and view of government there was no common ground between Roosevelt and Churchill, Hitler and Stalin, except that they were adept politicians, gaining control of their respective governments, the president by free election, the prime minister by circumstance, the German leader by treachery, and Stalin by cunning manipulation.

Here the commonality ends. Roosevelt typified the oldest America. His Groton-Harvard-Hyde Park background was as remote from Hitler’s as the White House was from Berchtesgaden. Churchill’s childhood landscape was the estate at Blenheim Palace. His Marlborough heritage, his education at Harrow, were fitting for a man of honor. Stalin’s early years were spent in a seminary, until his cunning and determination led him on the path to power. Hitler was the son of an illegitimate father, a product of a state public school, a Volksschule rooted in discipline and Austrian/German nationalism, and ultimately a product of his manifesto, Mein Kampf.

Neither Churchill, nor Roosevelt, nor Stalin could imagine such a focused fanatic, a conspirator who in singular focus, organized revolt, and revolution had taken control of a land that had produced some of the most respected scientists and composers, artists, and writers. He would go on to write a masterful if deranged script for its destiny, its future history.

Historical drama does not stand still, however. Sooner or later, even for each of the conquerors with whom Hitler not unreasonably classified himself—Caesar, Alexander, Napoleon—the curtain must fall. For him as for them, it would fall on a tragedy.

Shares