In 2015, I penned an article for The Washington Post that was the first to look inside the Green Collection at the Museum of the Bible and profile the controversial museum’s uncontroversial director, respected scholar David Trobisch. What had brought the museum to my attention was not only the headline-grabbing facts that it was to cost half a billion to build, and the whispers that the ultra-conservative, evangelical Green family, of Hobby Lobby fame, were rumored to be preparing an enormous visitor-conversion machine (rumors of which proved overblown, as the museum experience is designed to appeal to a variety of religious beliefs and, thankfully, aims for objectivity). It was actually a talk given at the annual academic conference on art crime run by the research group I founded, ARCA (Association for Research into Crimes against Art). The paper was given by Roberta Mazza. In it, she highlighted some concerns about how the Green family was collecting the enormous quantity of Biblical artifacts. She showed slides of purchased objects appearing on eBay and sold by pseudonymous sellers with alleged links to looting and possibly even terrorism. She also showed videos of the previous director, before Trobisch took over, dismantling mummies in order to access Biblical texts that were written on the papyrus in which they were wrapped — a practice very much frowned upon by most scholars.

Mazza began to look into the Green Collection when researching fragments of a recently discovered papyrus by the ancient Greek poet Sappho:

I started searching information about [the collection] through the internet, and I discovered many details on the acquisition methods, and also on the ignorance in papyrology and conservation care of papyri shown by the ex-director of the collection, Scott Carroll. This man was able to buy about 1000 papyri for Mr. Green from 2009 to 2012. . . .

But Carroll was known for finding papyri for collectors — prior to the Greens, he worked for another Christian fundamentalist, Robert van Kampen, and acquired some 5,000 papyri for his collection. Again, from Mazza's research:

I found, and still find odd that so many papyri were available on the market in such a short period of time, and maybe by coincidence during the Arab Spring. How was he able to find first 5000 papyri and then another [approximately] 1000 [for the Greens] in such a brief period of time, and in the context, in theory, of a strictly regulated antiquities market? Is it possible that, in the past decade, there were at least 6000 papyri which, having legally left Egypt before 1972 (the year of the enforcement of the UNESCO convention) were sold by their owners?

The numbers are staggering. The UNESCO convention controls the export of antiquities, and makes it bureaucratically difficult to legally sell abroad objects that were excavated after 1972. The idea that thousands of papyri could be on the market means that private collectors with artifacts acquired prior to the 1970s had suddenly decided to sell them and flood the market — or that the papyri had been procured in a possibly illegal manner. Mazza continued, “I have been reassured by Trobisch that all acquisition documents are clear, but I am a scholar, so I need solid proof to be convinced. So far I have not seen any, while the videos and interviews [with Carroll] I saw and read were very worrying.”

Many of these videos have been taken off YouTube now, but Mazza showed some at the ARCA Conference on the Study of Art Crime in 2014 in Amelia. Carroll was shown handling ancient papyri and other artifacts in what appeared to be a manner that ranged from sloppy and haphazard to intentionally destructive. In one video, Carroll explains to a group of students how they will dismantle an ancient mummy mask, before dissolving it in Palmolive soap, pulling the cartonnage apart with toothbrushes, and laying out the strips to examine the text that they contain. This video led Mazza to dub Carroll “the Palmolive Indiana Jones.”

Mazza continued: “It suffices to watch Scott Carroll videos, read his interviews and tweets, to be concerned about both his acquisition methods and his questionable practice of destroying mummy masks, with the help of scholars and students of the Green Scholars Initiative, in order to retrieve texts.”

Harvesting mummy cartonnage is not illegal (provided you are the legitimate owner of the object and it was not excavated or exported illegally), but a question of ethics. As Mazza said, accepting this behavior “allows owners of antiquities legally acquired to dispose of their objects as they wish, even to destroy them,” and wonders whether some new legislation should be implemented that would hinder legal owners from destroying cultural heritage, even if they did acquire it legally.

There is a parallel in the world of rare books and prints. A dealer might buy a book containing dozens of antique prints, and then “chop” or “break" the book into pieces, harvesting the prints, which can be framed and sold individually, thereby making a profit far greater than the price of the intact book. This is not illegal, but is heartbreaking to bibliophiles. If someone bought a Picasso and sliced it into strips, selling each one to a different buyer, then the world would be up in arms. Why isn’t this the case with an ancient mummy?

At the ARCA conference, and published subsequently in her blog, Faces and Voices, Mazza described another problematic papyrus, which contains Coptic text from Galatians 2. When visiting the Green exhibit at the Vatican, Mazza recognized that the Galatians 2 fragment “had, in fact, been put on sale on eBay in 2012 by a much-discussed Turkish account, MixAntik.” When Mazza asked Trobisch about the origins of the fragment, she claims that he refuted her suggestion that it had been bought over eBay. But images and a description that match the fragment were indeed on eBay. These were the concerns Mazza addressed at the conference, which made me interested in the whole affair. But I was also intrigued that Trobisch attended the conference as an audience member (and not at invitation) to hear what Mazza had to say — a very professional move, and one that suggests a clean conscience. That’s what drew me to focus on Trobisch, who is not an evangelical, but a theologian with an impeccable pedigree.

I came away from research for that article thoroughly impressed with Trobisch, who green-lit the item-by-item investigation of the colossal collection, the reins of which were newly in his hands. I was still concerned about the accusations from respected scholars like Mazza, and they had not yet been answered.

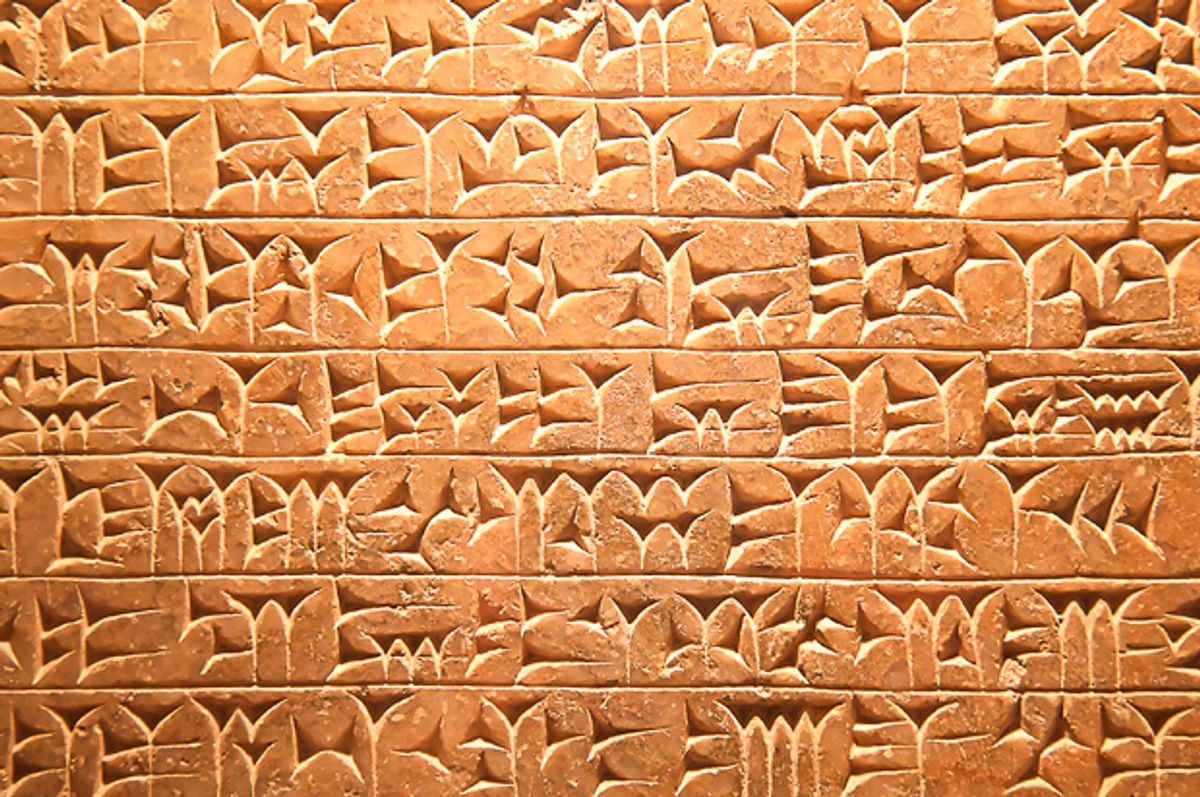

Turns out she was right. An investigation by the FBI, begun in October 2015, has recently concluded. Federal prosecutors announced July 5 that the Hobby Lobby Stores (not the Green family personally, it should be noted) have agreed to pay a fine of $3 million and to “forfeit thousands of ancient Iraqi artifacts smuggled from the Middle East that the government alleges were intentionally mislabeled,” according to the Washington Post. This was linked to a bulk purchase of around 5,500 objects, in December 2010, for a price of $1.6 million, many of which were shipped from the Middle East to the United States in ways that suggested smuggling and customs evasion, including labeling contents as “ceramic tiles” and shipping to a variety of addresses, to avoid suspicion that would come from mass shipments to a single one. A single shipment of 1,000 clay bullae was shipped, in September 2011, by an Israeli dealer with a fake customs declaration stating that the package came from Israel, when it did not. A United Arab Emirates dealer shipped packages with fake documentation that it was coming from Turkey. The federal investigators were concerned that these artifacts were coming from illicit archaeological sites, were looted or stolen, and were emerging from conflict zones like Iraq. It appears that these fears were justified. In the worst-case scenarios, some of these purchases may even be funding terrorist activity, which is not in the least unlikely, given their origins and the knowledge that fundamentalist terrorist groups fund their activities through antiquities looting.

Shares