Donald Trump won the presidency in no small part through his persistent demagoguery about urban violence, which he appears to believe is the result of our first black president refusing to enact "law and order" policies on communities of color. As with most things Trump believes, this is largely nonsense — overall trends show a precipitous drop in crime over the past two decades or more — but of course violent crime in cities hasn't been eradicated completely. That has allowed Trump to use the specter of violence to push for an expansion of already draconian and sometimes overtly racist criminal justice policies.

But a paper published in the May edition of the journal Social Science & Medicine, titled "The enduring impact of historical and structural racism on urban violence in Philadelphia," adds an intriguing piece of evidence to a growing body of research that links the history of racial discrimination in cities to current problems with gun violence. This research suggests that fighting systematic racism is a better solution to urban crime than the heavy-handed policing tactics prescribed by Trump and his supporters.

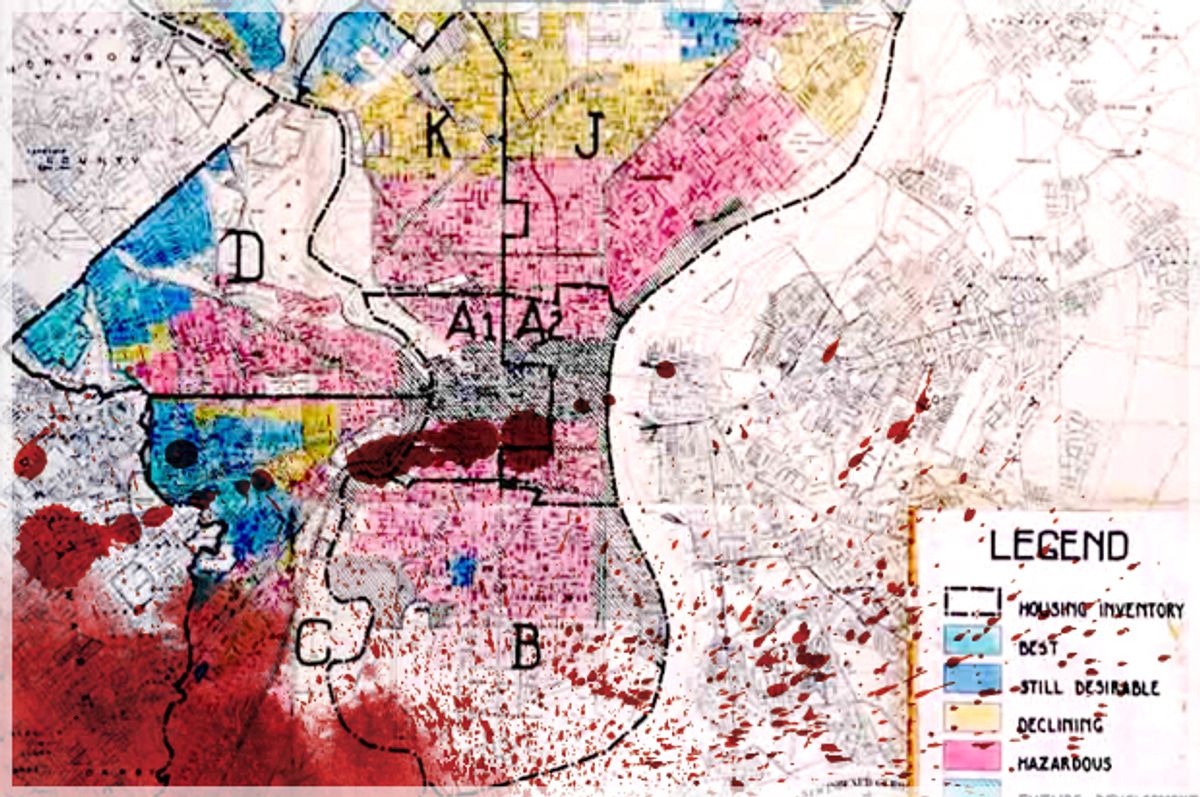

The researchers, who all work with the Penn Injury Science Center at the University of Pennsylvania, took a look at modern maps of gun-violence hotspots in Philadelphia and compared them to an infamous redlining map of the city produced in 1937 by the Home Owners' Loan Corporation. What they found was that areas of Philadelphia deemed "red zones" 80 years ago strongly correlate to areas that now have a high concentration of gun violence.

“I’ve been interested in the history of the city and racist policies that shape urban space," explained Sara Jacoby, an interdisciplinary postdoctoral fellow in the Penn Injury Science Center and the lead author of the paper.

Jacoby worked as a trauma nurse, often helping patients injured by gun violence in Philadelphia, before she embarked on her doctoral work investigating the racial and socioeconomic inequities in health care. In our conversation, she said the idea to compare modern-day maps of gun violence to the old redlining maps started as a thought experiment, but it developed into this paper after the initial comparisons showed intriguing correlations.

Federal redlining, as Alexis Madrigal of the Atlantic explained in a 2014 article, was a racially discriminatory housing policy created with the 1934 creation of Federal Housing Administration, which remained federal policy until 1968.

"Otherwise celebrated for making homeownership accessible to white people by guaranteeing their loans," Madrigal wrote, "the FHA explicitly refused to back loans to black people or even other people who lived near black people."

The FHA literally defined red zones, which were considered too toxic for guaranteed mortgage lending, as places that had "inharmonious racial or nationality groups," which in practice often meant red-zoning neighborhoods for having a large number of black residents. While there is some dispute over how much impact these maps had on actual mortgage distribution in Philadelphia, Jacoby argued that the maps represent "a marker or a reflection of the racism of the 1930s and '40s" and, as such, offer a good indicator of the ways historical patterns of discrimination can contribute to current problems.

“We can’t just look at a block in the city and understand the problem of violence from the firearm rate of the last 5 or 10 years," Jacoby argued. "These sort of dangerous spaces perhaps are purposeful and maybe a century in the making, and maybe they need more concentrated intervention.

"The hotspot itself is not about 'hot' people," she added. "It’s about places that have developed over time.”

This geographical and historical approach to the problem of gun violence and other racially-coded disparities is gaining traction in public health research. One reason is that it offers a better explanation than some of the approaches offered by conservative pundits and politicians, who want to claim that it's just bad people making bad choices, instead of looking at the bigger picture. It also opens up opportunities for urban planning and other government policies that could actually be effective at reducing violent crime.

“Perhaps those places that have been historically discriminated against might be a good place to target more intensive remediation of space," Jacoby said.

In his famous 2014 piece calling for reparations for centuries of abuse and discrimination aimed at black Americans, Ta-Nehisi Coates linked the continuing disparities of wealth and opportunity to America's history of racism. This paper helps place the disparate impact of gun violence on black and white Americans into this larger picture and suggests that the way to ameliorate the problem is to work on reducing our society's racial disparities, both in terms of wealth and other quality-of-life measurements.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration's approach to crime is the exact opposite. Trump appointed Jeff Sessions, a former Alabama senator and prosecutor with a lengthy history of alleged racist conduct and opposition to civil rights, as attorney general, the nation's top law enforcement official. Sessions has a long history of opposing policies aimed at righting historical wrongs and has even gone so far as to say that trying to address such inequities "has delayed the kind of movement to racial harmony."

Even without federal cooperation, some state and local governments could look as research like this and consider immediate solutions to address the geography of some cities in ways that might make them safer, friendlier and less conducive to gun violence. In the meantime, Jacoby hopes this paper can help start a smarter and more broad-minded discussion about the problem of gun violence in Philadelphia and elsewhere.

“When you spend a lot of time with patients and their families," she said, "you recognize how complex life is, and how complex the risk factors are that make you more or less likely to be injured by something like gun violence.”

Shares