If one good thing has come out of Donald Trump’s presidency, it is the increasing clarity about the current state of democracy in American and the country's drift toward tyranny. The election of Trump was a kind of wake-up call for many Americans who had become complacent or apathetic during the Barack Obama years, and it generated a widespread sense that something is profoundly wrong with our democracy.

Not surprisingly, some aspects of our political system have received a lot more attention (and blame) than other aspects. After last November’s election, for example, most Democrats were focused primarily on the Electoral College. This was to be expected after a Republican candidate who lost the popular vote was elected president by that archaic and undemocratic institution for the second time in less than two decades.

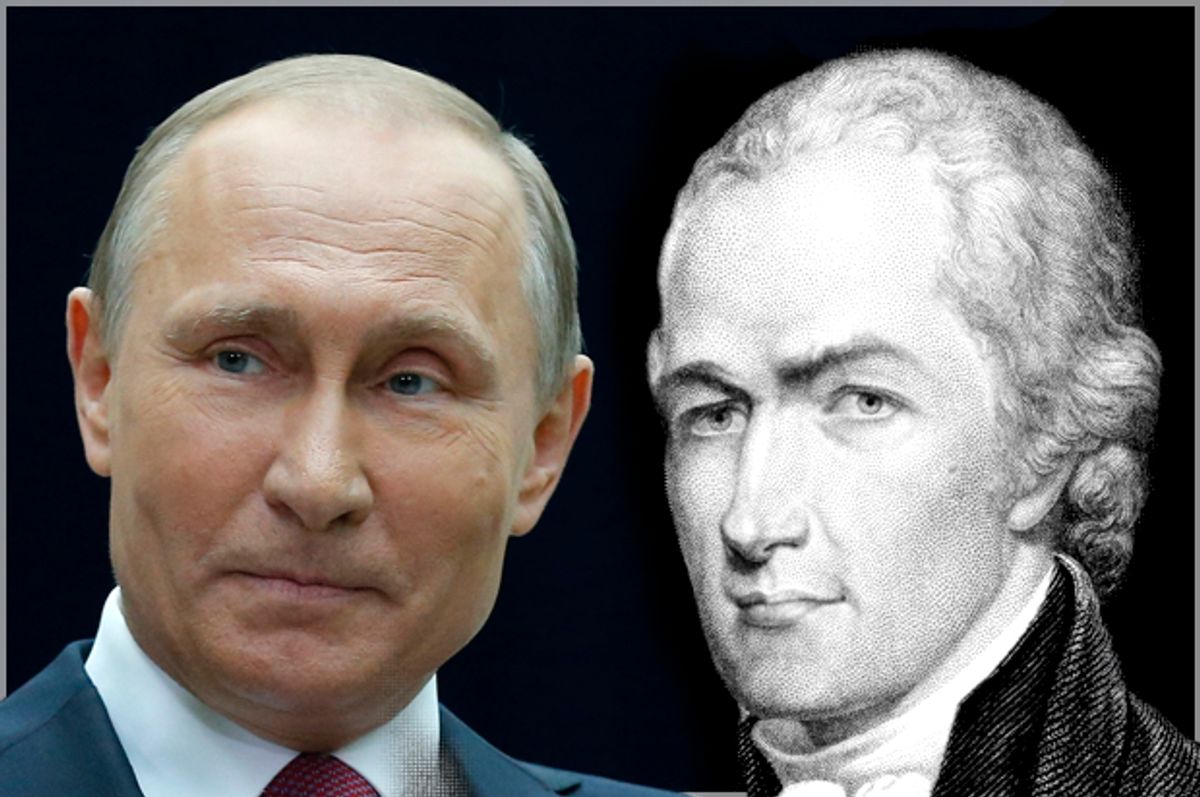

For the first month or so after the election, the Electoral College was probably the most widely discussed issue regarding American democracy. Some liberals even held out unrealistic hopes that the Electoral College would deny Trump the presidency. After that body made Trump's election official in December, attention shifted to another major story: How the Russians “hacked our election” and undermined our democracy.

That popular phrase is somewhat misleading, considering that there is no evidence that Russian hackers compromised vote counts or voter data. But there is little doubt that Russia sought to meddle in the 2016 election by hacking and releasing emails from the Democratic National Committee and Hillary Clinton's campaign. This scandal has arguably said more, however, about the negligence of the DNC and the Clinton operation than the state of American democracy. The hack into Clinton campaign chair John Podesta's computer, for example, apparently resulted from an embarrassing typo by a Clinton aide, who accidentally told

It is unfortunate, then, that the Russian interference — as disturbing as it is — has led many liberals to see Russia as the greatest threat to our democracy. According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, about 40 percent of Democrats now believe that Russia is the “greatest threat” to the United States. This is troubling for a number of reasons, particularly because it distracts from more legitimate (and internal) threats to our democratic process, while giving the false impression that American democracy was in good shape before the Russkies came along and “hacked our election.”

Trump’s victory seemed to open many eyes to the fact that democracy is in trouble -- but on the other hand, the Russia scandal has done more to obscure this reality than anything else. If anything it has led to the idealization of a deeply flawed and undemocratic political system, while renewing the myth of America’s commitment to democracy.

Of course, it is perhaps misleading to say that the United States' political system is “flawed,” as it was undemocratic by design. The founding fathers were notoriously wary of democracy, and as white landowning (and slave-owning) elites they devised a political system that favored white (male) landowning elites. As historian Woody Holton explains in his 2007 book, “Unruly Americans and the Origins of the Constitution,” the Constitution was essentially a response to too much democracy:

The wave of insurrections and threats that swept over the United States during the 1780s -- and more important, the [tax] relief legislation that the rebels managed to extract from lawmakers and local officials -- convinced many of the nation's more prominent citizens that the time had come to launch a rebellion of their own.

The form of government that resulted from this “rebellion” was meant to, in the words of the Constitution’s authors, “secure the public good and private rights against the danger of [the majority], and at the same time preserve the spirit and the form of popular government.” Deeply distrustful of the masses, the framers agreed that “enlightened statesmen” were alone fit to govern, and for the first century of the country’s existence only white male property owners were eligible to vote in most states, and only members of the House of Representatives were directly elected by voters (until 1913, U.S. senators were elected by state legislatures). The Electoral College is a recurring reminder of this original hostility toward democracy.

It is worth remembering these undemocratic origins today, because after more than a century of progress and democratic reforms the country has reversed course in recent decades. Big money has flooded the political arena, voter suppression has been restored across the country, and gerrymandering has grown so extreme that politicians can almost literally choose their constituents (rather than voters choosing their representatives). All of this was made possible under the political system that our democracy-averse founders created more than two centuries ago.

Indeed, the most undemocratic branch of government has been responsible for much of this devastation. Over the past decade the Supreme Court has essentially legalized political bribery with rulings like Citizens United and McCutcheon v. FEC, while dismantling important protections implemented by the Voting Rights Act, resulting in a surge of voter suppression laws across the country.

America’s political system was designed to limit the political influence of the majority, which makes this regression over the past few decades unsurprising. But the framers also crafted a flexible document that could be “accommodated to times and events,” as the first attorney general, Edmund Randolph, put it. As time progressed, democratic reforms were introduced and social movements transformed the country’s deeply undemocratic government. What this means, of course, is that the current drift toward an oligarchic form of government can be reversed -- but only when there are popular social movements that demand true democracy, as did popular movements of the past.

The election of Donald Trump has instilled a new sense of urgency in people to act, and the Trump administration is rightfully seen as an existential threat to our democracy. (The administration’s recent formation of a "voter fraud commission," led by Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, whom the ACLU has called the “king of voter suppression,” is further proof of this threat.) But a lot of this energy has been wasted on fruitless and self-indulgent endeavors, such as the quixotic effort to recruit “Hamilton electors” to refuse Trump the presidency or calls to impeach the president for his unproven acts of “treason.”

In the era of Trump, it is more important than ever to think critically, and to recognize that Donald Trump is not the cause of our ailing democracy, but a symptom of it. Trump's impeachment or resignation, taken in isolation, would do little to reverse our slide into tyranny. As the Russia scandal continues to pick up steam with the latest bombshell on Donald Trump Jr.’s potentially unlawful meeting with a Russian lawyer, it is worth remembering that American billionaire donors and corporate lobbyists are still a much greater threat to our democracy than Russian hackers.

Shares