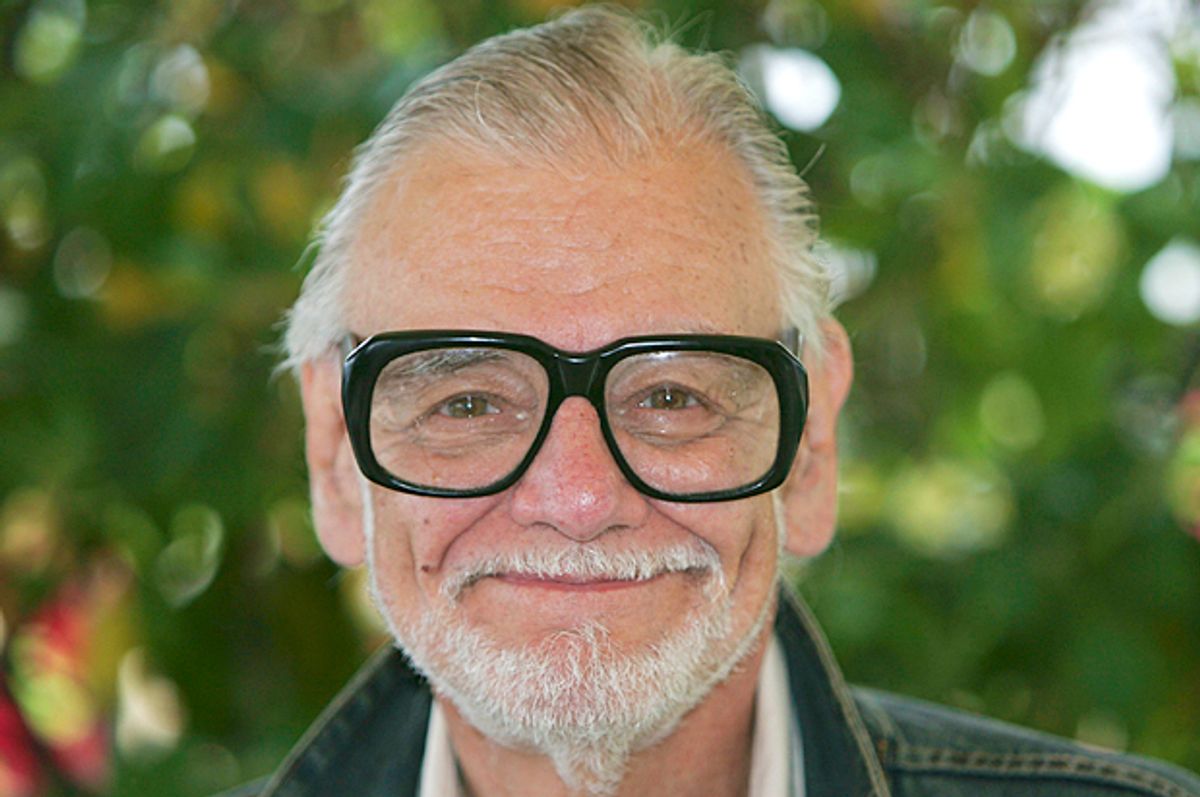

When reporters refer to George A. Romero as the "Father of the Zombie Movie," this is not intended as an insult. Romero did indeed create the modern zombie movie as it's known today — that is, one in which the zombies are the walking undead who crave human flesh rather than automatons controlled by a third party — and it is impossible to imagine "The Walking Dead" or "World War Z" or "Warm Bodies" without him.

At the same time, Romero — who passed away on Sunday after "a brief but aggressive battle with lung cancer" — didn't make zombie movies into an iconic genre simply because they were scary or gross. Indeed, an argument could be made that zombies aren't particularly thrilling in their own right as far as movie monsters go. They aren't very smart, they aren't physically threatening (except in the sped-up lamer version promoted by Zack Snyder in his "Dawn of the Dead" remake) and they don't have any personality or character of their own.

Yet they are surprisingly effective as horror movie baddies for one simple reason: They're highly flexible allegories for much deeper commentary about the horrors of human nature, war and even nature itself.

This is a point that Roger Ebert understood well in his glowing, 4-star review of Romero's "Dawn of the Dead" in 1979. He described it as "brilliantly crafted, funny, droll, and savagely merciless in its satiric view of the American consumer society" and insisted that "it is not depraved, although some reviews have seen it that way. It is about depravity."

As he aptly summed it up, the zombies are blameless from a moral standpoint, and "the depravity is in the healthy survivors, and the true immorality comes as two bands of human survivors fight each other for the shopping center: Now look who's fighting over the bones!"

Romero made similar social points in all of his zombie movies. "Night of the Living Dead" (1968) had an unmistakable subtext about racism, "Day of the Dead" (1985) was an allegory for militarism and "Land of the Dead" (2005) was about capitalism and class warfare. Romero's lesser zombie films that followed included "Diary of the Dead" (2007) and "Survival of the Dead" (2009) may have been less intelligent than their predecessors, but that did nothing to diminish their relevance or power.

So, when we remember Romero, we should do more than simply acknowledge his achievement in shaping an entire horror sub-genre. We must also remember that he taught us that horror movies could do more than contain characters who eat brains; they could have working brains of their own.

Shares