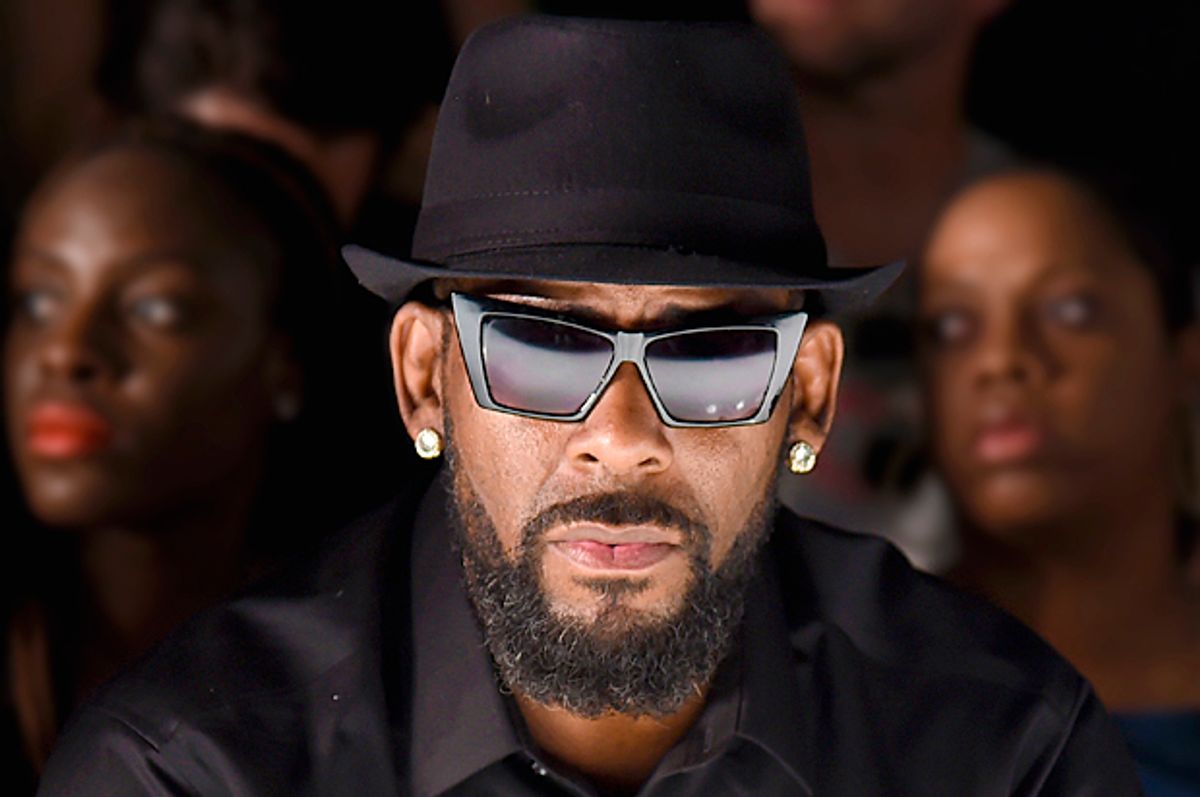

Even for a story about a man with a long and public history of deeply troubling behavior toward young women, there are still an astonishing number of horrifying and mind-boggling revelations in Jim DeRogatis' bombshell Monday Buzzfeed feature on R. Kelly's alleged "abusive cult." (Kelly's attorney denies the accusations, saying he "deserves a personal life.") At the heart of the tale, plenty of readers are wondering how any parent could put an adolescent child in the path of a man with such a well-documented predatory record. Those of us with teenaged daughters of our own are all the more disturbed and baffled.

Journalist DeRogatis has been covering the lengthy and "stomach churning" details of Kelly's interactions with teenage girls for 17 years now, since he first reported on the allegations Kelly "used his position of fame and influence as a pop superstar to meet girls as young as 15 and have sex with them" back in 2000. But the talk goes back even further, to Kelly's known involvement with teen girls, including his protege Aaliyah — in the nineties. Today, a whole new crop of girls not yet born during his 1996 "inappropriate sexual contact" lawsuit are reportedly under the sway of the now 50 year-old artist. DeRegotis reports three former members of Kelly's entourage allege that "six women live in properties rented by Kelly in Chicago and the Atlanta suburbs, and he controls every aspect of their lives: dictating what they eat, how they dress, when they bathe, when they sleep, and how they engage in sexual encounters that he records."

Heartbreakingly, the parents of one of the females in the alleged group tells DeRegotis, "He was going to help her with her CD, and I was really impressed with him at first, because I have always been an R. Kelly fan. . . . In the back of our minds, we were thinking [my daughter] could be around him if I was with her. It didn’t really hit home."

Whether it's a famous person or a religious authority figure, history has shown again and again how easy it is for abusers to exploit their authority — and the trust and admiration of those in their orbit. Who, after all, wants to make a scene? Who wants to make someone else uncomfortable or embarrassed, just for being affectionate, just for trying to help? Especially someone important?

I know enough of the statistics on sexual assault and abuse to know it can happen to anyone. As a mother of two teen daughters, if there were a vaccine I could give my kids to prevent anyone from ever hurting them, I would. But I can't. What I have tried to do has been to model, from the time that they were babies, is that they don't have to be pleasant and accommodating and deferential in a way that doesn't feel right for them for anyone, ever. I have backed them up every single time, for any reason, they didn't want to give anyone — including me — affection or closeness. They've never had to touch or be touched if they didn't want to, and they've never had to give a reason. No is reason enough. It doesn't have to be a big deal. Because I hope that in those moments when I'm not around, they can listen to their guts.

It sounds simple in theory, but it's not always so in practice. We've over the years endured well meaning but guilt-tripping distant relatives who just wanted a little hug. We've had children's birthday parties where my kids have squirmed away from their classmates, and missions to see Santa that were aborted. We've gotten up and moved away from subway sprawlers. For that, my daughters have at times been accused of not being "friendly" or "nice" or even "polite." And that's just fine. My kids have learned they can survive being accused of being unfriendly, because if someone reacts badly when you establish limits for yourself, that's not your problem.

Do I believe my daughters are immune to predators, especially ones who might seem like friends? God, I wish, but no. But I do hope they've learned about boundaries, because their conversation about consent began a long time ago. Abuse isn't always a single, violent act. It's often on a continuum of grooming that includes a lot of testing of the victims' — and their caretakers' — limits. And it's as insidious, and evil, as knowing how reluctant we often are to make a fuss.

Shares