What does it mean to make history? For Metropolitan Museum of Art design curator Christian Larsen, it can be a very conscious decision.

With his first exhibition for the institution, "Ettore Sottsass: Design Radical," which opened this week at the Met Breuer and runs through Oct. 8, the associate curator of decorative arts and design has set out to carve a place in the canon for a controversial figure in 20th-century design, architect and designer Ettore Sottsass.

“To get to the heart of it, the Met has a mandate of recognizing the best artists and designers and bringing them into what is [considered] by most people as the canon,” Larsen explained. “Sottsass is somebody who has been marginalized and dismissed from that very canon. Despite his fame in Italy, in the States he’s always been seen as being on the losing side of history,” Larsen says, posing Sottsass as a charismatic counterpoint to the slick, “form follows function” dogma of the dominant school of modernism.

An architect and designer with a wide-ranging output, Sottsass can be difficult to pin down. He was born in Austria in 1917 and died in Italy in 2007. Along the way, he became one of Italy’s most famous architects and designers, after establishing his studio in Milan in 1947.

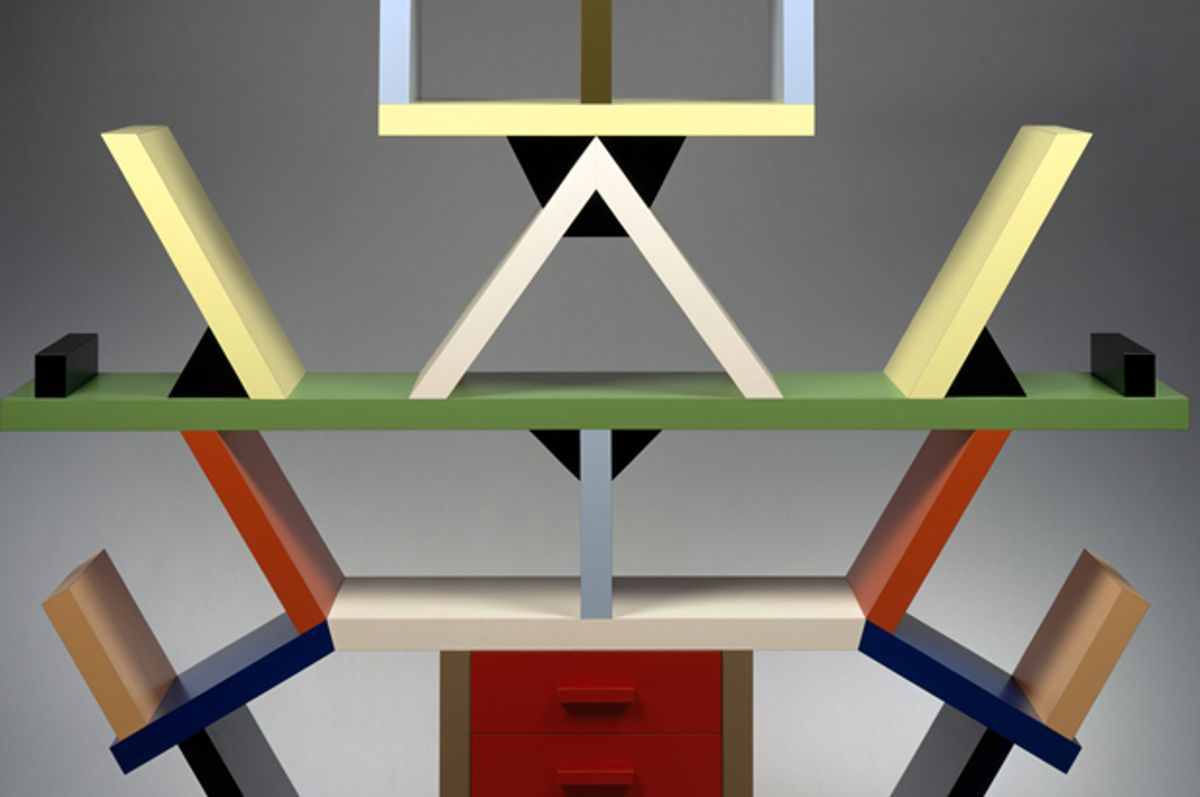

Though he worked in everything from glass to jewelry to interiors, he’s perhaps best known for his early industrial designs for Olivetti, as well as for his later work with the Memphis Group, the design collective he founded in 1981. A postmodernist movement filled with exuberant, geometric designs in colors that could even clash with themselves, Memphis design — which has nothing to do with the Tennessee city — is sometimes compared in a pop-culture shorthand to the visual style of "Pee-Wee’s Playhouse" or the opening credits of "Saved by the Bell."

It’s a movement that had a short lifespan, but one that inspired strong opinions along the way. In interviews, Sottsass recalled contemporary critics writing Memphis off as a joke, while others called it an affront to good taste or a substance-free status symbol driven by trends. But Sottsass had influential fans as well; a recent Sotheby’s auction revealed David Bowie to be a major collector.

In recent years, contemporary design has again taken a turn for the bold. From the introductions at Milan’s annual Salone del Mobile (the industry’s most important trade show) to the emerging designers covered by the taste-making online magazine Sight Unseen, there’s been a marked resurgence of the color blocking and energetic (and sometimes cheeky) forms of Memphis — one that, it could be argued, is now nearing the end of its run in the trend cycle.

For his show, Larsen acknowledges this contemporary revival by filling the galleries with pieces from throughout the Met’s collection, as well as with an extension of the exhibition to the gift shop, where one can buy totemic collages by Jamie Julien Brown and marble stools from Oeuffice, both created this year, alongside editions of Sottsass’ own Tahiti lamp.

Today, it’s easy to see connections between things separated by time and space, thanks to our increasingly unfettered access to the vast world history of images. Take Tumblr or Instagram, for instance, the digital feeds where one image flows into the next. For official narrative of the visual arts and design, it’s a different sort of story.

Sure, it’s undeniable that artists often have influences. Creative movements shape the next, whether through a slow artistic evolution or by inspiring reaction and rebellion. But often, the way that story is told is much more isolated snapshots. It’s a modernist approach, one in which moments are examined in the clinical isolation of the white-box gallery.

Taking a cue from Postmodernism itself, Larsen’s exhibition takes a transhistorical mix-and-match approach more in line with Tumblr feeds or the wide-ranging collections of the cabinets of curiosities from centuries past. As he puts it, “I could have done another straightforward retrospective, yet again present him as a kind of sui generis wacky genius that is unconnected to history and may not be relevant, [but] here at the Met we have 5,000 years of art and design to draw from, so why not use it as a way of explaining where he comes from, what are his influences, why he’s important — how he used those influences to try to revise modernism.”

In the exhibition, which spans the museum’s third floor, Sottsass’ work is juxtaposed with pieces plucked from throughout the museum’s encyclopedic collection. Necklaces from the 1980s by Sottsass and his Memphis cohort are shown next to pieces from Egypt’s Middle Kingdom in one particularly poignant pairing. Graphic artworks by Roy Lichtenstein and Frank Stella are showcased near an installation of blocks covered with Sottsass’ laminates, squiggly patterns with evocative names like "Bacterio," and ancient ritual objects are shown alongside his ceramics to illuminating effect.

And then there are moments of contrast, the most dramatic of which is that of Sottsass’ designs with the venue itself: Marcel Breuer’s Brutalist building, a ziggurat-like form executed cooly in the tasteful modernist palette of concrete, granite, and glass.

At times it’s a compelling mix, but at others — like an arrangement that seems to say more about Japanese designer Shiro Kuramata than the exhibition’s subject — it can feel like a curator overeager to play with the iconic collection at his disposal. While it’s a thought-provoking exhibition, one can’t help but think of the axiom that correlation isn’t always causation. Still, it’s a visually stunning arrangement, and perhaps that is enough.

“If Postmodernism taught us anything it’s that you can mix and match and do whatever you want. It’s a pastiche,” Larsen said. It’s a lesson, demonstrated in this exhibition, that lives on — in design, in the exhibition of art, and perhaps, even in the shaping of history. And that may be just as radical as Sottsass’ work.

Shares