Don’t young people know how to enjoy a failed rock festival anymore? The doomed Fyre Festival is not the first music festival to be canceled at the last minute. As a child of the ’60s, I attended another “disaster” — the Powder Ridge Rock Festival — scheduled over a three-day weekend in the summer of 1970.

By that time, rock festivals had played an important role in forming the countercultural identity. Is it any wonder that we baby boomers have been given the label “Woodstock Generation,” after one of the most significant music festivals of that era?

After Woodstock, failed festivals became common, often due to eleventh-hour changes resulting from local opposition. The Powder Ridge event, which booked Fleetwood Mac, James Taylor and Janis Joplin, among other music icons, was banned because of an injunction brought by neighboring residents who feared that hordes of long-haired concert-goers would decimate their community. But 30,000 of us arrived anyway, many camping out days before the banning of the festival, to find a lack of food, plumbing and music. Yet we stayed the weekend on that ski slope in Middlefield, Connecticut, and made the most out of our escapade.

This was a sharp contrast with how the upwardly mobile millennials handled the situation at this year's aborted Fyre Festival in the Bahamas. The opulent music event promised big-name acts such as Blink 182 and Major Lazer, as well as gourmet food, luxury accommodations and famous models and social media “influencers” like Kendall Jenner and Bella Hadid. When the reversal occurred on the morning of the event, near panic conditions ensued, resulting in the evacuation of the 400 festival-goers who’d arrived, out of the 8,000 actual ticket-holders.

Instead of the top contemporary musical artists expected at Fyre, a few local bands played on an undeveloped gravel pit. Powder Ridge, on the other hand, featured popular folk-singer Melanie, the only scheduled act to risk arrest by performing on a makeshift stage powered by a Mr. Softee ice cream truck.

Twitter and Instagram postings from Fyre complained about disappointing food rations — processed cheese sandwiches and a side of salad. Free alcohol was available, at reportedly understocked bars, to appease the guests waiting for accommodations. When we headed off to Powder Ridge, my three friends and I packed peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, a couple of bottles of cheap Chianti and a few Alice B. Toklas brownies.

Lodging at Fyre was in disaster-relief tents with damp mattresses, conditions that seem lavish by comparison to Powder Ridge. Whether coincidence or karma, soon after arriving at our prohibited music gathering, we ran into three good friends who had already set up a pup-tent and had a supply of food and beverages. We unrolled our sleeping bags on the ground next to them, combined our provisions, and had a home base for the duration.

Chartered planes to and from the tropical island fest were eventually grounded, causing festival-goers to be holed up for hours without food or water waiting for their return flight. We Powder Ridge attendees had our own transportation hazards. As my friends and I drove from our campus in the Bronx into rural Connecticut, at one point being stopped and searched by the police, we encountered a posted sign stating, “Festival Canceled. Turn Back.” That didn’t stop us. As the Woody Guthrie song goes, “But on the other side it didn’t say nothing,” so we persevered. After all, Woodstock, the summer before, had nearly been halted too.

At Fyre, the island was reportedly surrounded by shark-infested waters (which the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism has denied). We had our own perils of nature — the pond many of us went skinny-dipping in was later declared polluted and off limits by the authorities. As I hiked above the crowds, attempting to be at one with the local fauna by passing through some bushes and trees to an adjacent cow pasture, I was repeatedly shocked by a hidden electric fence before figuring out what was happening.

How to account for the differences in how millennials today and boomers back then dealt with ill-fated music festivals? The large sum of money ponied up in advance might cause one to feel a greater sense of loss and resentment. Fyre was supposed to be an exclusive, high-end festival — a Woodstock for the wealthy — costing $1,500 to $12,000 and even upwards of $250,000 for deluxe packages. We hippies had put up $20 for the entire weekend at Powder Ridge. When rich millennials shell out that much money, their expectations become raised and the stakes become higher. They take a bigger hit when reality sets in.

We youthful boomers saw music gatherings as a pilgrimage, and as such, we anticipated a certain amount of hardship and sacrifice. On our way to Woodstock, the New York State Thruway and other roads were closed down, jammed with cars. My boyfriend and I were left to hitchhike and walk 10 miles to the celebration, riding part of the way on the hood of a car going 5 mph, unsure if we’d even get in. The police search endured on my way to the terminated Powder Ridge concert the following summer seemed a necessary penance to pay, and luckily set us back only a short time.

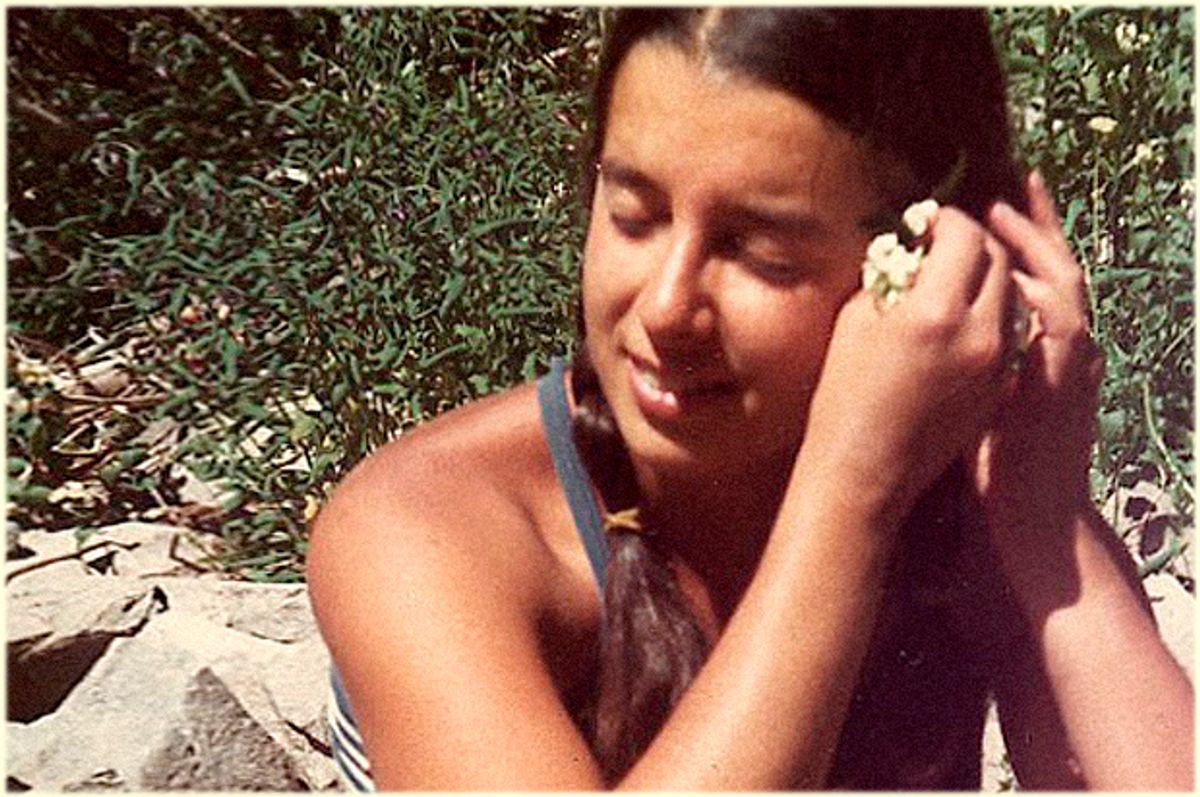

The author, circa 1970

Just as other pilgrimages have a spiritual purpose, the journeys we took to these music festivals did too — to worship the god Rock. But at Powder Ridge there was minimal music, no focal point, as there had been at Woodstock. When Melanie played, it was a religious experience. We saw ourselves as a movement of young people congregating not only to pay homage to the music, but for the energy and excitement of a shared experience. Having come of age in the time of be-ins and happenings, we had a “Be Here Now” mentality that drew us to these rock festivals, whether they took place or not.

Concert-goers at Fyre got upset when reality didn’t measure up to their exorbitant expectations. At Powder Ridge we created our own reality. Our aborted music festival became an adventure and a time to celebrate. The deluge of selfie-Instagram reports coming out of Fyre took concert-goers out of the experience of the moment. In today’s world, even Woodstock might be considered a failure: “What, no Wi-Fi?”

The number of lawsuits filed against the organizers of Fyre Festival is a dozen and counting, many of them class actions on behalf of ticket purchasers and patrons. The number of lawsuits against the Powder Ridge promoters (not including the initial injunction) was zero — and we had a good time. This is how we did a failed festival: We didn’t spend a fortune, and we didn’t need to sue.

Shares