Recent summers on the vast, white expanse of the Greenland ice sheet have featured some spectacular ice melt, including an alarming period in 2012 when nearly the whole surface showed signs of melt. But this summer has instead seen several bouts of snow, staving off a big summer melt. So what gives?

While it may seem contradictory, those snows are actually something Greenland may see more of with global warming, as the atmosphere becomes primed to dump more heavy precipitation. And while that snow may insulate the ice sheet against major melt this year, focusing on one summer risks missing the forest for the trees. Because make no mistake, Greenland is still melting, dumping water into the ocean and causing global sea levels to steadily rise.

“We’re still pumping a lot of ice” out to sea, Marco Tedesco, who studies Greenland at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said.

As Arctic temperatures rise at about double the rate of the planet as a whole, Greenland’s surface has been melting at a steady clip, contributing about 30 percent of the foot of global sea level rise since 1900. And summer is prime melt season, when the sun’s rays beat down on the ice, causing meltwater to pool on the surface and drain down through the ice sheet and out to sea.

Those rising seas will slowly inundate coastal cities; many already see more so-called sunny day flooding, impeding traffic and flooding basements. The surging waters pushed ashore by hurricanes and other storms is also getting higher and causing more costly damage.

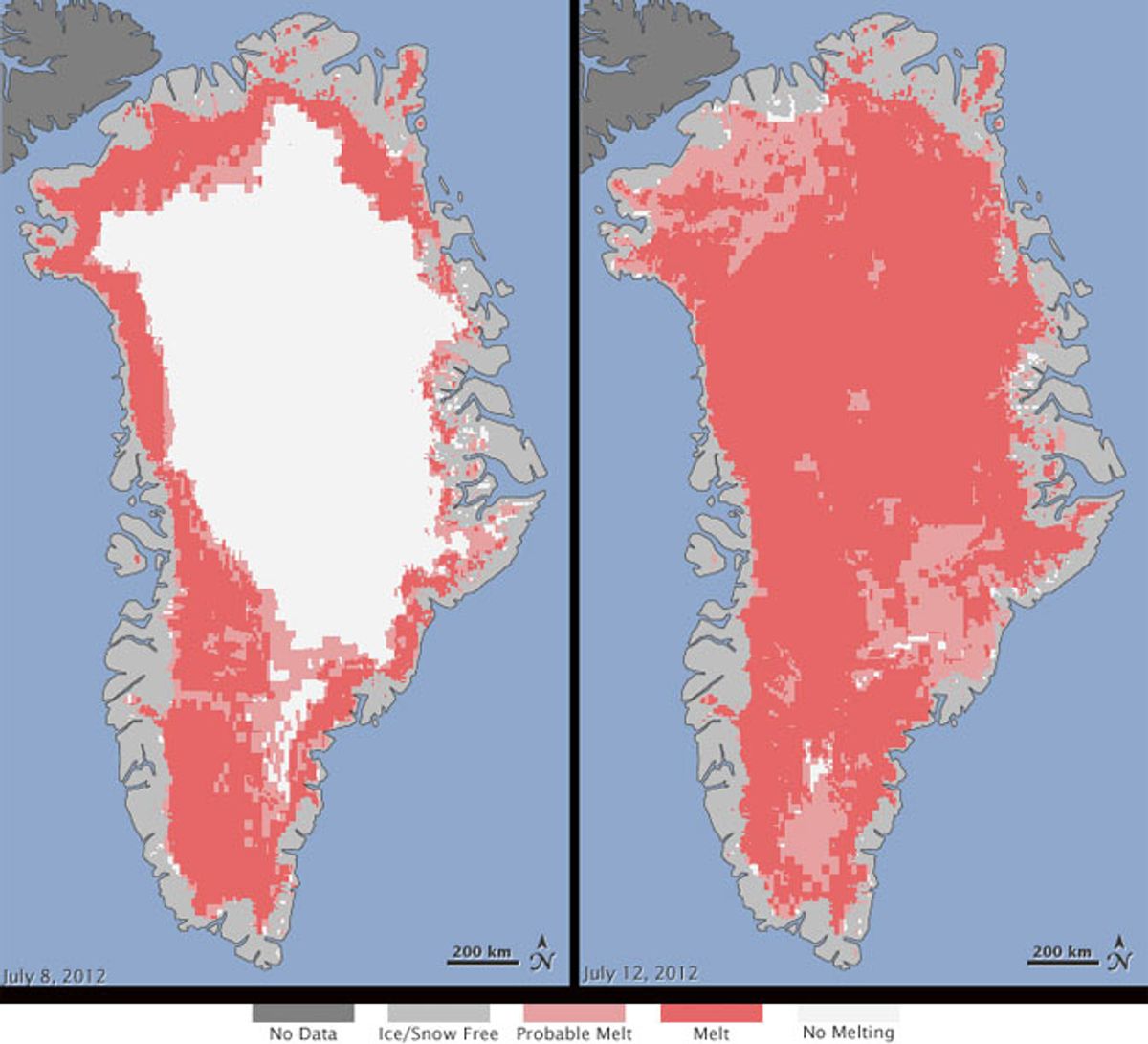

Several recent summers have seen particularly stark ice loss: At the peak of the 2012 melt season, about 97 percent of the ice sheet surface was melting — that melt season alone contributed 1 millimeter of global sea level rise. Last year, the melt season started two months early thanks to high temperatures across parts of the island.

But this year has been noticeably different. It all started in October, when big snowstorms “really loaded Greenland up,” Jason Box, a glaciologist at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, said. “That really preconditioned this year for low melt because it thermally insulates the darker ice below.”

Essentially, it takes a lot more solar energy to get rid of that layer of bright, white snow, which reflects more solar rays back to space than darker layers of ice or meltwater.

While there were some bouts of melting earlier in the summer, the weather has since shifted. In recent weeks, summer snows have topped up that already unusually high snow load. Right now, the ice sheet’s surface has about 1.2 times the amount of mass than normal; at the same point in 2012, it had 1.2 times less than normal, Box said.

Also inhibiting summer melt this year is the unusually southerly position of the jet stream, caused by a climate pattern called the North Atlantic Oscillation. “That’s keeping Greenland relatively cold,” Box said.

While snowy weather may seem at odds with a warming world, Greenland could actually see more of it as temperatures rise. A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, which means that when storms pass through, they drop more precipitation. When temperatures are below freezing, as they are for much of Greenland through most of the year, that means more snowfall. (Rain has been falling at the expense of snow in the lower third of the island as temperatures rise above freezing, though.)

Previous research by Box using ice cores — long cylinders drilled out of the ice sheet that let scientists sample hundreds of years of ice layers — showed that in the past, snowfall has increased over the ice sheet as temperatures have risen.

For the first decade or so of this century, there were more clear skies over Greenland, and so increased melt. But atmospheric patterns seem to have flipped around in recent years, and Tedesco and others are still working on figuring out how changing atmospheric patterns might be influencing snowfall and melt on the ice sheet to better predict how it will progress with future warming.

This year’s excess snowfall doesn’t mean that melt isn’t still happening, though. Melt has already picked back up since the last summer snow earlier this month, Box said. In fact, he expects that that snow will now be a layer of slush he’ll have to trudge through when he arrives on the ice sheet this week to check on a network of weather stations.

The snow could, however, balance out the year’s melt, Box said, with the ice sheet ending up with no net loss of ice for the year — the first year that will have happened in two decades.

One year without a net loss also doesn’t buck the long-term trend of Greenland losing ice, both from surface melt and from ocean waters eating away at glaciers that flow out to sea.

The increase in snowfall “is about four or five times smaller than the increase in surface melting,” Box said. So “the Greenland ice sheet is losing mass overall.”

Shares