In popular culture, the only good religion is generally no religion. With few exceptions, even Christianity, has been reduced to a simple pagan symbol with a smiley face on it. If it’s orange, it’s Halloween. If it’s green and red and sparkly, Christ is born and so on. When religious characters pop up in movies and TV there’s either something wonky and old-fashioned about them or something unforgiving and scary, like in-laws or terrorists. The common plot: a character whose old-world, cartoonish parents want them to marry into their religious heritage only said character loves someone more secular and therefore modern and “open-minded”— read white (see above) — who’s really nice and American!

On some level, the reason for this drift towards secular neutrality is a combination of fear and close mindedness. The end result, “Yentl” notwithstanding, is a lack of nuance in the way, Hollywood and even the publishing industry parses and portrays religiously observant communities, especially Muslim ones. They are either all good or all bad but always all backwards in both cases. What is missing in these representations is that within these Muslim communities of faith there are, of course, levels. Not just levels of observance, but all the facets of humanity, both the good and bad, as there are in the secular world. There isn’t just religious and non-religious. Or all terrorists all the time. The obstacle: convincing the publishing or producing powers to give communities of faith a platform where they can merely exist is like throwing rocks at the sky or digging through granite with a needle.

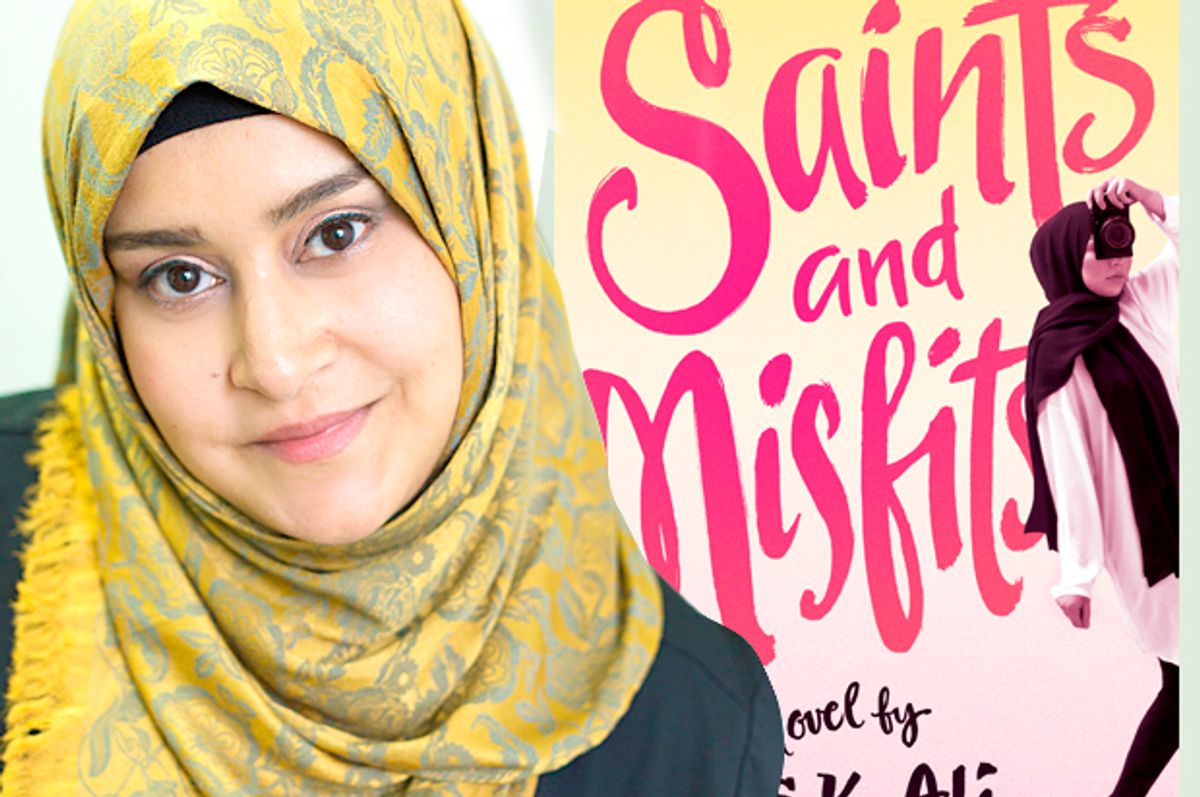

Just ask Muslim-Canadian YA novelist S.K. Ali. She is also the author of “Saints and Misfits,” the first YA novel published about a hijab-wearing character that has been published by a Big Five Publisher —the only other book from a major publisher is from Australia, “Does My Head Look Big in This”— so there’s a certain amount of pressure to “get it right” on both sides of the fence, to appeal to secular readers and show them, hey, observant Muslims are teenagers too, and to portray the Dreaded Religion as an inspiring part of daily life rather than a hindrance.

Unlike adult fiction, YA is written for that deranged season in life when it’s especially essential to fit in to a particular group. What’s more, we all fear that we are Carrie (not Bradshaw but White) and that one day we will get tampons thrown at us in the shower. This is why the most successful YA books depict some kid stepping outside the group (also known as that icky comfort-zone thing) to change who she is in the world of the book and as a result changing the world itself because she’s in it.

As a Muslim-Canadian writer of YA, however, this is doubly the case. Just as you might fear being rejected by one group, now there are two. By the same token, when you step outside the world to change it, both you and your world are forever changed, not in that hokey, it’s-a-small-world-after-all way, but in a way unique to what S.K. Ali ascribes to the actual demands of having an almost dual identity — being a teen, fitting in, but also staying true to faith, community and oneself.

Only here’s the thing: most of the white people who go ape on social media about the evils of religion have never actually read their own Ur-text. They hate Christians as perpetrators of all the isms even though they themselves are mostly Christian. Religion is viewed as the death of reason and the fear of it tentacular reach spawns science marches. It follows then that these secular-ites who have made a religion out of fearing religion have not remotely perused, say, the Qur’an, though they have a lot to say about its followers, such as: whether or not women should wear hijabs or niqabs and what is or isn’t the appropriate swimming costume to wear on what beach.

“I wanted to challenge what was expected of me,” Ali tells me over the phone. “What I read didn’t make sense in Muslim identity but it was written by non-Muslims and it had nothing to do with my life or my faith. When I was writing in high school, I was mimicking what I was reading: middle-aged white women like Judy Blume. Of course, I loved her, but then university made me explore writers who were writing authentically, pushing that away, and that’s when I discovered my writing voice, it was a dual identity, and it was raw.”

“Saints and Misfits” is a poignant exploration of how a faith-based community exists and thrives in a secular, unforgiving world. We first meet the protagonist, high school sophomore Janna Yusuf, as she awkwardly emerges from the ocean in her burkini. Subsequently, her friend’s cousin Farooq, a boy from their mosque who has memorized the entire Qur’an, sexually assaults her. This incident and the confusion and shame surrounding it, form the core wound that drives the novel. Janna keeps Farooq’s assault on her to herself as she attempts to navigate life. She crushes out on a non-Muslim boy at school, cares for her elderly Hindu neighbor, takes part in an Islamic quiz-bowl team, and develops a friendship with a niqab-wearing girl who turns out to be an empowering ally when she least expects it.

“Sometimes I sense a weariness from Muslim readers,” Ali says. “Because you get bad representation fatigue. But I wanted to explore both how religious Muslims derive spirituality from their religion — it’s not really known as spiritual but it is — and I wanted to explore what the world would look like if someone had gone through trauma. Growing up, that was a spiritual teaching, how do you strike a balance between patience and action.”

Recounting a story about the prophet Muhammad, Ali tells me about the supposition that Muslim women are meek but actually she was taught to speak up from an early age. Learning as a young girl that the first Muslims pushed aside the norms of slavery and challenged gender inequity actually sparked her nascent feminism. It is this revolutionary spirit that continues to inform it today.

“There are so many more stories that we have to see and hear,” Ali says. “I hate to have it like, okay, we have our Muslim-girl book.” She sighs and then says, “We’re not all about rules and we’re not all one type. My next book explores Muslim love because people need to know that happens. It’s important to also show joy in our communities, not just, you know. . .” She trails off, then adds, “We’re humans not robots!”

Book by book, a slow accretion of ideas might be around the corner to open minds and topple this resistance, ideas that might make certain readers feel better about Muslims and Muslim faith in America today, but then again who knows. S.K. Ali is up against a lot but she is poised for take off.

Shares