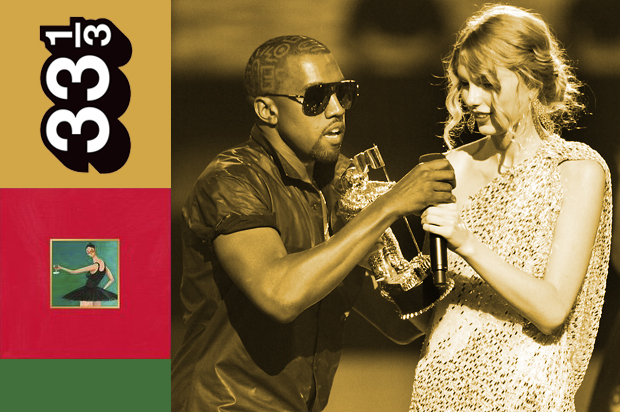

Throughout his career, one of the most appealing and appalling parts of Kanye’s persona has always been the doubleness of his ego — a weirdly complicated childish streak that charms and disgusts in the space of a single gesture. Watching footage from the infamous 2005 Katrina relief telethon, you can measure the shakiness in his voice with a seismograph. What he wants to do, his shaky voice tells us, is gather up all of the floating corpses and detritus and outrage in New Orleans, smash it into a bolus of righteous indignation, and fling it splattering into the living rooms of an ignorant and apathetic public. What he does is something different. Rather than bear witness to a moment of political courage by a precocious pop star, we see an embarrassingly inarticulate person who, though he yearns to say something meaningful about racial inequality and America’s permanent underclass, talks instead about feeling guilty for shopping. That tension — a struggle between self-rationalized good intentions and reckless execution — is an animating force in West’s life and music. So much so, in fact, that in spite of the status he enjoys as beat maven and rap genius, a plurality of the American public associates his name not with a corpus of inspired baroque rap futurism, but with two high profile and incendiary incidents that occurred during live TV broadcasts. The first of these, call it the “Bush Push” … was an unsolicited verbal sucker punch to a sitting U.S. president. The second incident was, of course, the buffoonish hijacking of Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards. His intentions were, once again, avowedly noble — you see, he stole Swift’s spotlight to shine it on the more deserving art of someone else (Beyoncé). He was the corrective principle of the pop universe, he was deconstructing the tastelessness of award shows, he was etc, etc, etc. The stunt was a bridge too far. The Taylor Swift brand is a sacred force in the marketplace, an ocean of commodified self-regard for millions upon millions of tweens, teens, and twentysomethings around the world. The outburst was self-destructive on a spectacularly visible scale, and in his usurpation of an otherwise unremarkable moment, he may have permanently alienated an entire generation of women. For those who already found his records distasteful, his antics proved his music to be the bombast of a narcissistic clown, the meretricious noise of a child drunk on his own Kool-Aid. His reputation grew to accommodate a host of social grievances, from incivility to race baiting to celebrity entitlement. The worst moment of his public life got its own meme on the Internet, when people across the globe began digitally superimposing his image on unrelated photos, captioning each one with some variant of his infamous interruption (“Imma let you finish, but. . .”). After an August during which political antagonism over healthcare reform became a blood sport in town hall meetings across the country, Americans found a vital center in their shared disgust at West’s behavior. Watching his stillborn come-to-Jesus moment with Jay Leno a few days after the incident, it was clear that for Kanye West, atonement would require a lot more than penance. It would take a miracle.

More than any other poet of spiritual exile, Dante gave the world its most elegant rationale for taking time to figure shit out: “Midway through the journey of our life / I found myself within a forest dark, / For the straightforward pathway had been lost.” No less than Don Draper, the wayward enigma at the heart of Mad Men, meditates on those first lines from the Inferno while sunning on a beach in the show’s sixth season. And why not? The image endures down through the ages as a catechism of what it means to be human, a sentient and mistake-making creature adrift in the chaos. Given his compulsion for grandiose analogy, and his positive genius for self-deporting from the straightforward path, the image of Dante’s wanderer is a fitting one to describe the state of things for Kanye following the Swift debacle in late 2009.

Complex magazine editor-in-chief Noah Callahan-Bever became a Kanye confidante over the years, and in early 2010 West invited him to spend time at Avex Honolulu Studios in Oahu, where My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy was recorded. Since a prophetic 2002 profile in Mass Appeal magazine (where he describes West as “hip-hop enough to appeal to the most thugged-out cats, but thoughtful enough to resonate with the underground”), Callahan-Bever has charted West’s trajectory through the cultural ecosystem, providing anecdotal glimpses into an inscrutable psyche. For the November 2010 Complex cover story “Project Runaway,” he provides an indispensable eyewitness account of the process by which our era’s most dynamic pop star conceived his magnum opus.

Recounting a phone call with West in mid-October 2009, he writes: “Kanye West was over it, he said. Done with music. He’d clearly needed a break, and his subconscious had manufactured one. Now, he was all about fashion — red leather, gold details, and recapturing the decadence of late-’90s hip-hop in design. While I encouraged his pursuit since he was so obviously enthused, I confessed that it’d be a bummer if he abandoned music altogether.” West was calling from Milan, having left the country following the Leno appearance. He spent a few weeks in Japan before jetting to Rome, where he began an internship at the Italian fashion house Fendi. Reminded of the trying circumstances behind the creation of the Rolling Stones’ greatest LP Exile on Main Street in the south of France, Callahan-Bever admits he was intrigued by the possibilities of Kanye abroad. After a few months with little real communication, he received a brief email in January 2010 from the expat rapper: “Yooooooo, happy new year fam. I can’t wait to play you this new shit!!!!” By late March, Callahan-Bever was “at Avex Honolulu Studios, the seaside recording studio on Oahu where West tracked [fourth studio album] 808s [& Heartbreak]” and where he had block-booked “all three session rooms, 24 hours a day” until he was satisfied that the new album was complete.

One of the joys of reading NCB’s piece is his clear-eyed rendering of both the process and the stakes interwoven in the album’s production. He recounts matter-of-factly the hypomanic rhythms of West’s machinations:

Meanwhile, Kanye stares at his laptop, jumping between email and 15 open windows of art references in his browser. He polls those assembled on how risqué is too risqué for his blog, and occasionally barks mixing orders at the engineer, tuning subtle parts of the beat – all without breaking eye contact from his computer. This is how he works: all-A.D.D. everything.

None of this is surprising to anyone who has listened to the album, which is as much about aesthetic transformations of manic energy as is it is about anything else. “During my five days in Hawaii,” NCB writes, “Kanye never slept at his house, or even in a bed. He would, er, power-nap in a studio chair or couch here and there in 90-minute intervals, working through the night. Engineers remained behind the boards 24 hours a day.” Even more compelling is NCB’s account of the shared awareness among the production’s many players:

But mostly we talk[ed] about Kanye’s album: what it has to mean, and what it has to accomplish. At its heart, beyond the beats or rhymes, this conversation is the reason we were all summoned to the island (no LOST). It’s never explicitly discussed, but everyone here knows that good music is the key to Kanye’s redemption. With the right songs and the right album, he can overcome any and all controversy, and we are here to contribute, challenge, and inspire.

Callahan-Bever expresses an unpretentious wonderment at getting to participate in “Rap Camp,” the playful moniker he gives to his time embedded in the album’s production. Likening the experience to a camp — a clinic put on by some of rap’s leading lights — makes a lot of sense. If you bother to take a census of the dozens of artists, producers, and engineers who worked on MBDTF, it’s easy to forget you’re not looking at the credits of a major motion picture. In addition to the sweeping scope of the production and the vivid after-images etched by its blaze of excess — the undeniable visual dimension of the surplus sonics — MBDTF feels like visual art in other respects, as well. The more one learns about the collaborative intricacies of the production, the more tempting it is to look at Kanye as director, as compositional auteur.