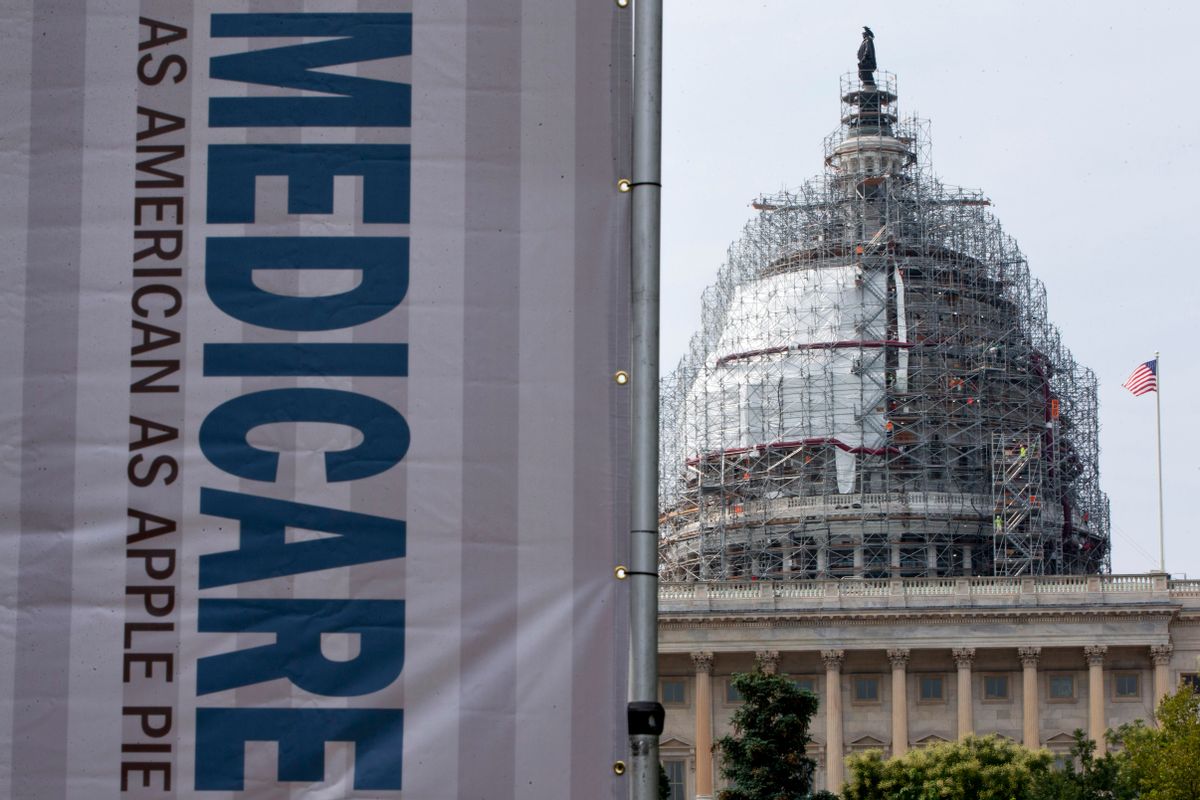

Watching the craziness in the Senate this week, as Mitch McConnell and the GOP’s zealots drove their clown car into a brick wall and yet another effort to take away health care coverage from millions crashed and burned, I thought back to a different turn of events.

It was 52 years ago this Sunday — July 30, 1965. Two American presidents celebrated the birth of Medicare, the most significant advance toward national health insurance in America’s history.

I was a White House assistant at the time, working for President Lyndon B. Johnson as he coaxed, cajoled, badgered, buttonholed and maneuvered Congress into enacting Medicare for the aging and Medicaid to help low-income people. For all the public displays over the years of his outsized personae and powers of persuasion, this time he had kept a low profile, working behind the scenes as his legislative team and career health care experts practically lived on Capitol Hill, negotiating with members of Congress and their staffs.

From the White House, LBJ worked the phones; invited senators and representatives singly and collectively in for coffee, drinks or dinner; listened attentively in private to opponents and proponents from interests as varied as business, labor, medicine and religion; and kept in his head a running tally of the fluctuating vote count.

As it had been for decades, it was a tough fight down to the wire. A look back is instructive, not only to show how long it can take to move a legislative dream to reality but also to illustrate how a president with a grasp of history and knowledge of how government works is crucial to making success possible.

In 1935, when President Franklin Roosevelt first tried and failed to get health insurance included as part of Social Security, I was 1 year old and my family was broke. The Great Depression had ended my father’s tenant farming. He took a job for a dollar a day as a laborer on the construction of a highway in southeast Oklahoma.

Earlier, my mother had lost twin girls — one at birth, the other some months later — because the nearest doctor was too far away to arrive in time to help. My parents moved into town. To pay the doctor who delivered me, my father lugged large stones by hand to the site the physician had bought to build his first office. It’s still there.

At about this time in Washington, Republicans, conservative Democrats and the American Medical Association (AMA) were winning their fight to sink President Roosevelt’s proposal for health insurance. Congress was intimidated, and in August 1935 FDR gave up, signing the Social Security Act without health coverage.

Eight years later, in the midst of World War II, he once again called for social insurance “that will extend from the cradle to the grave.” And again, his proposal went nowhere.

On FDR’s death, Harry Truman became president. In his 1948 Message to Congress on the State of the Union, he said:

This great nation cannot afford to allow its citizens to suffer needlessly from the lack of proper medical care. Our ultimate aim must be a comprehensive insurance system to protect all our people equally against insecurity and ill health.

Congress still refused to budge. Running for election in his own right that year, and way behind in the polls, Truman won an upset victory after demanding that health care insurance and civil rights be included in the Democratic Party platform. That same year, congressman Lyndon Johnson of Texas, whose home district was Democratic and liberal in a state turning increasingly Republican and conservative, was running for election to the US Senate. He opposed Truman’s health care plan as socialistic and was elected.

In 1952, Republicans won control of Congress for the first time since 1932 and hardened their stand against a national health care program. War hero Dwight Eisenhower won the presidency for the Republicans. He, too, opposed the plan that had been shelved by Congress before Truman left office.

Ike only was willing to support subsidizing private insurers to cover certain low-income groups and no more. With the continuing opposition of the nation’s doctors — amplified through their political lobby, the AMA, as well as the US Chamber of Commerce — the notion of Medicare appeared finished once and for all.

Yet when he yielded the presidency to Eisenhower, Truman lamented his failure but was prophetic when he said: “[It] has only delayed and cannot stop the adoption of an indispensable health insurance plan.”

He was right. The battle heated up. In 1957, the AFL-CIO brought its 14 million members to the fight. The American Hospital Association, which bore the brunt of the problems older people encountered as they aged, signed on, too.

Public opinion was swinging in favor of national health insurance. When John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson were nominated as the Democratic ticket in 1960, they made health care for Social Security retirees a major plank in the platform and endorsed a bill in the Senate that in time would become Medicare.

Though he was Kennedy’s running mate, Johnson was still the powerful Senate majority leader, that body’s top Democrat, and responsible for steering its legislative agenda. After a long day on the campaign road, or in the Senate, we would get to his home late and he would stay up until after midnight, making phone calls to one or another member of Congress urging passage of the Medicare bill.

Despite his efforts, it failed by four votes. LBJ had studied the polls and knew public opinion was building for national health insurance; he feared this defeat might cost Democrats the election. It didn’t, although the margin of victory was incredibly slim. As soon as they were inaugurated, now President Kennedy and Vice President Johnson championed yet another effort known as the Medical Care for the Aged bill. Still adamantly opposed by the Republicans and the AMA, it also failed — this time by two votes.

In early 1963, the bill was reintroduced in Congress, only to fail again. Some observers again pronounced it once and forever toast. But in November of that year, an assassin killed John Kennedy, tragically catapulting Lyndon Johnson into the White House. Just days later, in a dramatic speech to Congress and the nation, he slowly and deliberately drawled: “Let us continue!” With that challenge, LBJ set out to enact Kennedy’s legislative agenda — with a good chance, he thought, of passing the Medicare bill.

As before, the opposition fought back with everything they had, which now included the AMA’s new pitchman, Ronald Reagan. Not yet a candidate for public office, the actor was hired to warn the country against letting government get between doctors and their patients. He made a popular recording played at thousands of small meetings around the country in which attendees heard his pitch warning of “socialized medicine” and predicting “behind [Medicare] will come other federal programs that will invade every area of freedom as we have known it in this country.” Just think if he’d had Twitter.

Our strategy that year came to naught, producing in the early fall a stalemate. The Senate actually did pass a national health care bill for the elderly (despite the opposition of the Republican nominee for president, Barry Goldwater of Arizona, who interrupted his campaign and returned to Washington to vote no). But the powerful and conservative Democratic chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, Wilbur Mills, would not agree to a medical care provision of any kind. A conference meeting to work out differences between the House and Senate ended in deadlock.

Johnson gritted his teeth and returned to the campaign, winning a four-year term in his own right.

Elections matter — surely no one doubts that fact anymore — and the ’64 election mattered dramatically. Not only did it deliver LBJ a landslide victory, but it brought Democrats their biggest majorities in the House and Senate since FDR. “If we can’t get Medicare through now,” the president told me after the election, “we don’t deserve what we just won.”

So as soon as he and Vice President Hubert Humphrey were inaugurated in January 1965, we started over. You can get a glimpse of the intensity of LBJ’s drive from a conversation I had with him around that time. With others, I had urged that the new bill include a provision for a retroactive increase in Social Security payments as an economic stimulus. He called me to say okay, but wanted me to understand it wasn’t because of the economy:

. . . My inclination would be . . . that it ought to retroactive as far back as you can get… because none [of the elderly] ever get enough. They are entitled to it. That’s an obligation of ours. It’s just like your mother writing you and saying she wants $20, and I’d always sent mine a $100 when she did. I never did it because I thought it was going to be good for the economy of Austin. I always did it because I thought she was entitled to it. And I think that’s a much better reason and a much better cause and I think it can be defended on a hell of a better basis. . . . We do know that it affects the economy . . . it helps us in that respect. But that’s not the basis to go to the Hill, or the justification. We’ve just got to say that, by God, you can’t treat grandma this way. She’s entitled and we promised it to her.

He understood the legislative process like no one I ever met. “Nothing given, nothing gotten — that’s the rule!” he told us in an Oval Office meeting on how to break yet another Capitol Hill deadlock. He sent his senior legislative aide to play sweet with a still-recalcitrant Wilbur Mills and warned, “I’ll tell you this, Wilbur Mills will take your pants off unless you’ve got something that he’s got to trade for.” When Mills still wouldn’t budge, the president let loose a string of invectives that would have made even Anthony Scaramucci blush. The next day he was courting Mills again, as if nothing had happened.

As the cherry blossoms bloomed that spring of ‘65, the president thought Congress was moving too slowly. The civil rights movement was under siege in the South, violence was continuing against blacks and we were working around the clock to pass legislation to end discrimination. Even so, he wouldn’t let us slow down on Medicare — or other pending priorities. When he thought we were lagging, he took us to the woodshed, as you can see in a telephone conversation with Vice President Humphrey and me:

They [the House and Senate] are bogged down. The House had nothing this week — all goddamn week. You and Moyers and Larry O’Brien [his chief congressional expert] have got to get something for them. And the Senate had nothing . . . So we just wasted three weeks . . . Now we are here in the first week in March [1965], and we have just got to get these things passed . . . You’ve got to look each week and say, what is the Senate doing in committee this week and when will they be through, what is the House doing . . . You’ve got to be running into these guys [members of Congress] in the halls, and going over and having a drink with them in the evenings . . . I’ll put every Cabinet officer behind you, I’ll put every banker behind you, I’ll put every organization that I can deliver behind you . . . I’ll put the labor unions behind you.

A few days later, breakthrough. LBJ’s now-gentler courting of Wilbur Mills paid off, and the House Ways and Means chairman pieced together a bill from several options championed by different interests. He got it past the committee’s conservative coalition with a straight party vote, 17-8.

Remembering our defeat the previous fall, our team fretted over how to make the final sale to the full House and Senate. The president had some more advice for us. As he told Larry O’Brien, the White House chief legislative honcho: Give bragging rights to anyone who voted on the final version of both Medicare — and the big education bill also in the pipeline:

[Tell them] that every guy that votes for Medicare and education, his grandchildren will say my grandpa was in the Congress that enacted these two . . . So it makes ‘em proud. And they can go back home and say I was one of the 54 [who voted yes], or my daddy was one of the 54 . . . so all his children and grandchildren are bragging about being one of the 54.

Medicare passed the House by a vote of 313-115. But in the Senate, liberal Democrats added $800 million to its cost, outraging conservatives (and vexing LBJ, who knew such overreach would give opponents more fuel to attack).

Back the bill went to a conference committee between the House and Senate. Then to the House floor again, where it survived more than 500 amendments before passing on July 27 by majority vote, 307-116. One day later the Senate passed it, 70-24. All that was needed now was the president’s signature and Medicare and Medicaid would become the nation’s first public health insurance programs.

And that’s how it came to pass that 52 years ago, on the morning of July 30, 1965. President Johnson loaded up two planeloads of dignitaries and headed toward Independence, Missouri, hometown of former President Harry Truman. He intended to sign the bill at the side of the man whose original proposal LBJ had dismissed as socialism. Now he revered Truman as “the real daddy of Medicare.” Here’s the actual moment Medicare became the law of the land:

After signing the bill, Lyndon Johnson turned to Harry Truman and signed him up as Medicare’s first beneficiary. It was high drama, touched with history, politics, sentimentality, showmanship and compromise.

The legislation was far from perfect. LBJ once told me never to watch hogs slaughtered before breakfast and never ever show young children how legislation gets enacted.

Too much secrecy surrounded the bill’s passage. Even as the president signed it into law, we weren’t sure of all that was in there. As some principled conservatives warned, there were too few cost controls. The experts feared copays and deductibles would become a burden.

“Those can be fixed,” LBJ said, “once it sinks in that Medicare is here to stay.”

Meanwhile, as historian Robert Dallek has written, although Medicare and Medicaid did not solve the problem of care at reasonable cost for all Americans, “the benefits to the elderly and the indigent… are indisputable.”

Perhaps the biggest mistake was one of imagination — our failure to anticipate the advent of new and expensive technology to treat the sick or the demand on the system that would rise from a burgeoning population. That spring President Johnson had warned, “We will face a new challenge and that will be what to do within our economy to adjust ourselves to a life span and a work span for the average man or woman of 100 years.”

That, and the cost, we reckon with today.

Now that the eight-year effort of conservatives to repeal the Affordable Care Act (itself a flawed but significant extension of the effort to help more people get decent coverage) is stalled, the next steps are crucial. Going back to the status quo — a system driven by the profit motive and rationed health care based on income — is unthinkable. At the website Common Dreams, Dr. Carol Paris, president of Physicians for a National Health Program, writes:

“Clearly, the system is broken. Like a cracked pipe, money gushes into our health care system but steadily leaks out. Money is siphoned into the advertising budgets of insurance companies and the army of corporate bureaucrats working to deny claims. Even more dollars are soaked up by the pockets of insurance CEOs who have collectively earned $9.8 billion since the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010. Nearly a third of our health care dollars go to something other than health care.”

Yes, our health system is broken, but broken systems can be fixed — not easily, but they can be fixed.

Watching recent events, I thought of the long and arduous process I’ve just related, the many steps that brought Medicare into being, and how I was afforded a modest role in the supporting cast.

I came away from the experience with three lessons. First, whether health care is a right may be debatable, but it assuredly fulfills a basic human need — and without it, human beings without means will live and die suffering unduly.

Second, building that more perfect union which the founders of this republic defined as the mission of government has always been slow, hard, acrimonious, frustrating, tiring and elusive, because we as individuals are ourselves imperfect and because there are always among us those predators who regard democracy as an obstacle to their avarice.

Against such realities, the only way for democracy to succeed is for enough people to take up the cause where and when they can, as so many did for Medicare and are doing now for our eroding social covenant. That’s the third lesson I learned: It is harder to build something than to burn it down, but build we must.

Shares