According to a biographer of Donald Trump, “He’s been lying his whole life, almost reflexively.”

Now, President Trump may be lying to his team of private lawyers who are handling issues relating to the investigation into Russian meddling in the election. Last month, Trump’s personal lawyer, Jay Sekulow, told Meet the Press “the president was not involved” in drafting a misleading statement describing a meeting at Trump Tower between campaign members and a Russian lawyer in June 2016.

But when the Washington Post reported that the president had “personally dictated” the statement, the White House confirmed that Trump “was personally involved” in drafting it.

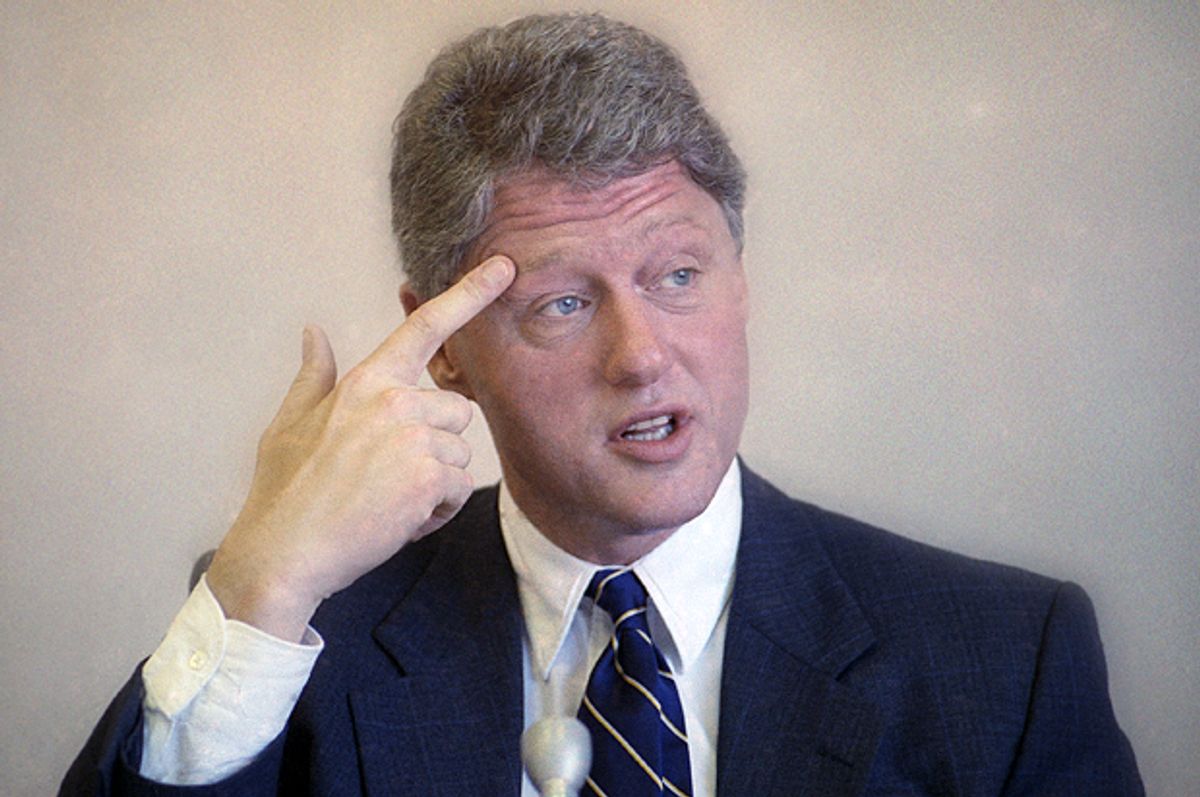

Failure to be truthful with his private lawyer is what led to former President Bill Clinton’s impeachment. At the heart of the Articles of Impeachment brought against Clinton was the charge that he gave “perjurous, false and misleading testimony” and allowed his attorney to make “false and misleading statements” in a sexual harassment lawsuit brought by Paula Jones.

As a scholar of legal ethics, I teach my law students that if Clinton had been truthful with his lawyer, it’s likely he never would have been impeached. Like Clinton, Trump badly needs advice from lawyers who are fully informed of the truth. In the opinion of many legal experts, the pattern of misleading statements about the Trump Tower meeting has already increased Trump’s exposure to criminal prosecution or impeachment. The stakes have just been raised with news that Special Counsel Robert Mueller has obtained grand jury subpoenas in connection with the Trump Tower meeting.

Clinton’s impeachment

When Clinton was forced to testify in the Jones lawsuit, his personal lawyer, Robert Bennett, attempted to block questioning about Monica Lewinsky. Bennett showed the judge an affidavit in which Lewinsky stated “I have never had a sexual relationship with the president.” Clinton’s lawyer described the affidavit as “saying that there is absolutely no sex of any kind in any manner, shape or form, with President Clinton.” Bennett then asked Clinton if “never had a sexual relationship with the president” was “a true and accurate statement as far as you know it?”

Clinton answered under oath: “That is absolutely true.”

In a later court filing, Bennett admitted the Lewinsky affidavit was false. But in his autobiography, Bennett insists when he told the judge there was “absolutely no sex of any kind” between Clinton and Lewinsky, “I believed it with all my heart.”

If Bennett is to be believed, at the time of Clinton’s testimony he was unaware that Lewinsky had engaged in oral sex with Clinton. We can also infer he did not know, as Clinton explained in later grand jury testimony, that his client was interpreting the affidavit’s phrase “never had a sexual relationship” as not including oral sex.

If Clinton had told his lawyer the full truth, Bennett could have advised against Clinton’s disastrous word-game about the meaning of “sexual relationship” — advice that if taken would probably have prevented Clinton from committing perjury, thus avoiding later impeachment.

As explained by the American Bar Association, there is an ethical rule that would require Trump’s lawyers to treat everything he tells them with complete confidentiality. Trust is “the hallmark of the client-lawyer relationship” so that a client can “communicate fully and frankly with the lawyer even as to embarrassing or legally damaging subject matter.”

![]() In my view, Trump should learn from Clinton’s mistakes to never put his lawyers in the position of making statements in his name that later turn out to be false. Clients who don’t tell lawyers the full truth not only lose the benefit of wise advice. Even worse, as Clinton found out, inadequately informed lawyers may inadvertently do their clients great harm.

In my view, Trump should learn from Clinton’s mistakes to never put his lawyers in the position of making statements in his name that later turn out to be false. Clients who don’t tell lawyers the full truth not only lose the benefit of wise advice. Even worse, as Clinton found out, inadequately informed lawyers may inadvertently do their clients great harm.

Clark D. Cunningham, W. Lee Burge Chair in Law & Ethics; Director, National Institute for Teaching Ethics & Professionalism, Georgia State University

Shares