Steve Earle is one of America’s most prolific and powerful songwriters. For additional recreation, he writes novels, short story collections and plays. He also is a committed activist in the causes of death penalty abolition and the improvement of services for children, like his own son, who have autism.

I waited for him in a classroom at Chicago's Old Town School of Folk Music, where Earle was playing a show with his blazing country-rock band, the Dukes. The room was for piano instruction, and children decorated the walls with drawings of themselves accompanied by the lists of songs they have learned on their instrument. Earle makes his entrance already talking to the piano instructor – a soft-spoken, middle-aged woman in a blue dress and white sandals – who will take the room and begin her class in 30 minutes, leaving Earle just enough time to touch on topics as diverse as Allen Ginsberg’s advice to poets, contemporary country music and the battle of the Alamo.

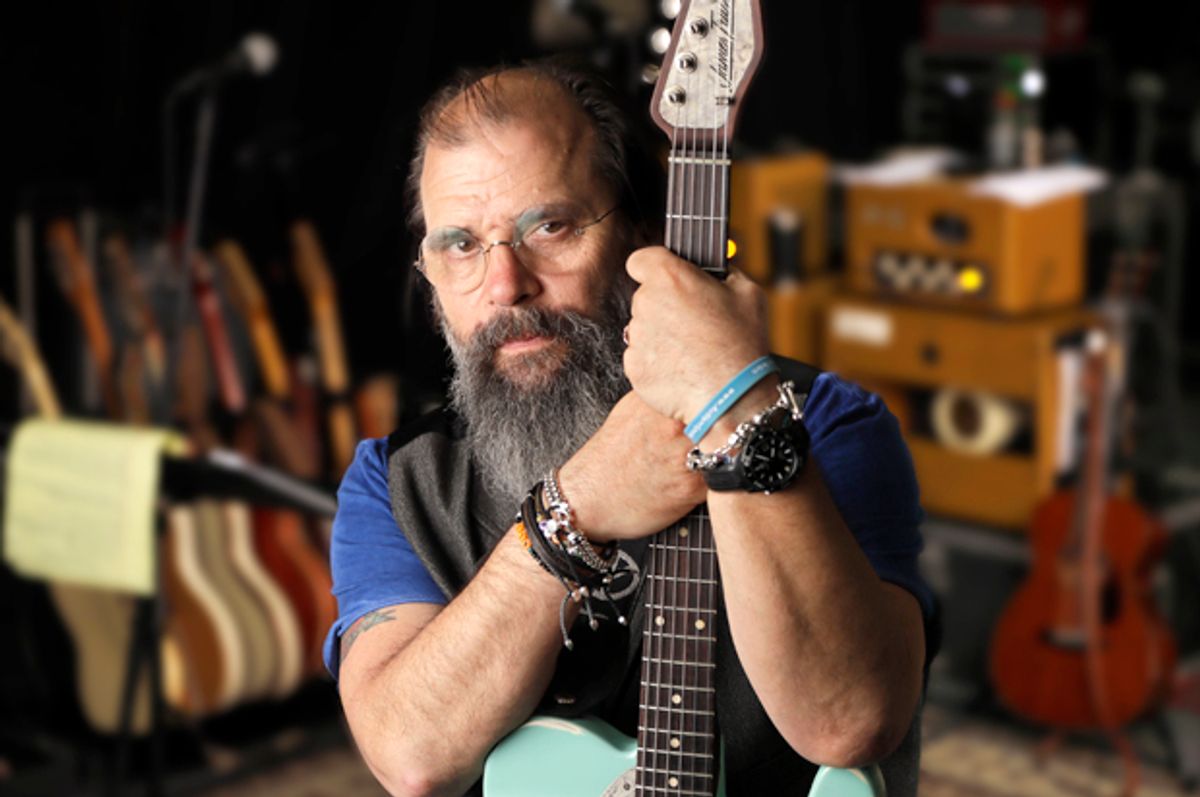

Earle, sitting in a chair directly across from me and unable to stay still, shifting his body weight with every sentence and toying with the bracelets on his wrists, also references the few months he spent in prison, his heroin addiction and still-growing 22 years of sobriety, and the years he spent touring with Bob Dylan. The violent contrast of the mountain Earle has climbed, and the swamp he has endured, led me to state the obvious: “The range of experiences in your life must give you a unique perspective on not only our society, but all of humanity.”

“Everyone has a unique perspective,” Earle fired back while almost lunging forward in his seat. “I am what I am. You are what you are. The guy down the street is what he is.”

One insistence about his identity that Earle articulated multiple times is that he is “not a political songwriter”: “I write more songs about girls than anything else.” Recently divorced from singer and songwriter Allison Moorer, and having established and dissolved several other marriages, Earle has plenty of material.

Earle’s personality coalesces a few fascinating elements into one unpredictable and unlikely force of nature. He is a tall, broad-shouldered man who looks like he could handle himself in the jailyard, but he is also a self-professed “romantic.” He is a bohemian who adores his home in Greenwich Village, but he is also a roughneck. “I still talk like this,” Earle said when explaining why he has never strayed too far from the country music of his origin, and what he talks about is often country: his childhood in Texas, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and the decades he spent living in Tennessee, especially the “good old days” when the New York Yankees had a Double-A team not far from his home.

If anyone ran a tally of love songs, lusty come-ons, and breakup ballads juxtaposed against the amount of political protest anthems and socially conscious story-songs in Earle’s catalog, they would have no reason to doubt the singer’s assessment. It is Earle who, more than anyone, contradicts himself when he pontificates at length on all matters political in response to most of my apolitical questions. At first Earle’s lack of cooperation with my questions frustrated me, but the task of the interlocutor, to borrow a phrase from Buddhism, requires “egolessness.” It is simply to inspire fascinating people to say interesting things. My agenda was insignificant compared to the unmoored exploration and expression of his mind. It is a mind that is as impressive as his music.

His new music, “So You Wanna Be an Outlaw,” is reminiscent of Earle’s early records that rightfully earned him the reputation of one of the best, and most rebellious, “outlaw country” artists since the emergence of the label. The title track, a duet with Willie Nelson, and the song, “Looking for a Woman,” are exactly what Nashville should produce in place of the endlessly derivative drivel dominant of mainstream country radio. “Fixin’ to Die” sounds like what would result if Slayer decided to write a country song. Earle, in full rasp showing the wear and tear of tobacco, screams, “I’m fixin’ to die / I reckon I’m going to hell,” over distorted guitar and fiddle.

Earle dismissed the prevalent “return to his roots” summary of the new record with the claim that he never grew too far out of them. “I suspect for people who like to separate music into piles, and slap labels on them, I never got out of country as much as people thought, but it is an acknowledgment of where I come from.

“The lunatics were running the asylum when I got to Nashville,” Earle remembered. “There was a group of young songwriters flocking around Guy Clark, and there was a group of long-haired bluegrass players around John Hartford. Those two worlds interlinked, because they were both worlds of hillbilly hippies. I fit into both.”

“Maybe it will happen again,” Earle said with some hope in his voice. “Chris Stapleton has managed to break through, and the girls are doing the best stuff.”

The influence of Waylon Jennings, whom he thanked during his performance the evening I interviewed him, and other outlaw country singer/songwriters, is as much musical as it was cultural. “Suddenly, I was standing in a field listening to the same bands as the guys who used to kick my ass.”

Earle’s career has promised to perform an unusual synthesis, and has made an unexpected transition. “My audience in the beginning was working-class, blue collar, redneck,” he explained, “And now I have an NPR audience.”

A friend of mine, who while in the Army was stationed in Texas, remembers how whenever the nearly perfect songs of “Guitar Town” or “Copperhead Road” would blast out of the jukeboxes of beer joints near the base, the Southern soldiers, oil workers and miscellaneous drinkers would loudly sing along through their slugs of whiskey. It sounds like a corner of heaven, but now the characters who populated Earle’s early music are likelier to vote Trump, raise the confederate flag, and applaud Republican calls to cut funding for public radio and television.

The rightward drift of Texan politics continues to baffle Earle, even though beginning as a young boy in his hometown of Schertz, located just outside of San Antonio, he intuitively, and later intellectually, understood that there were two states of Texas, just as there are two Americas – one the property of myth, and the other a genuine historical place.

“This country exists so that the second and third sons of English and Dutch families could get another whack at the piñata with slavery in their tool box after it was made illegal elsewhere,” Earle said, stretching out his answer to my question about Waylon Jennings. “The battle of the Alamo was fought because Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna attacked Texas because they were holding slaves, and we aren’t taught that in school. Everyone who held land grants agreed to convert to Catholicism and not to hold slaves, because slavery was illegal in Mexico, and that’s why the Texas revolution was fought. I was never taught that in school. No one is.”

Settling into his role of biker balladeer meets history professor, Earle continued his memoiristic lecture. “I knew two black people when I was growing up, but whites had plenty of Mexican people to pick on, which was stupid because we were occupying Mexico. If Santa Anna had not fucked up and lost Texas then San Antonio would have been the capital of the province. I had an uncle who was a hippie who gave me my first Bob Dylan and Rolling Stones records, and he told me so I always knew. We stole Texas. We really lived in Mexico.”

“Dylan, by the way,” Earle began to tell me – his own reference to the masterful lyricist causing him to make a U-turn back to music, “is actually a genius.

“Songwriting is a form of literature. Cole Porter had literary chops but he dumbed it down to write pop songs,” Earle explained. “The original meaning of ‘genius’ is a level of excellence and invention that makes people think of whatever it is you are doing in a way that never previously existed. That is what Dylan did.”

As a songwriter who also creates textual literature, Earle is particularly qualified to assess Dylan’s Nobel Prize for Literature. He recalls a professor in New York asking for his response to a colleague who ridiculed the Nobel committee’s choice: “Tell him he’s a fucking idiot,” was Earle’s succinct reply.

“Everyone who does what I do – all of us singer/songwriters,” Earle offers, “we’re all just living in a room Bob Dylan built and sucked all the air out of a long time ago. We’re all chasing him, and we’ll never catch up.”

The influences Earle cites throughout the twists and turns of our conversations — Dylan, Ginsberg, Guy Clark, Waylon Jennings — were and are men who, like Earle himself, maintain an individualistic sensibility directly responsible for the atomic blast of their creative impact. They are also men who desire and manage to communicate important discoveries into the ancient mysteries art, popular or esoteric, is intended to investigate.

“Politics and art are not antitheses,” Earle explained when I mention the boring and mediocre point many conservative commentators like to projectile-vomit at entertainers who advocate for a certain set of political positions: Shut up and sing.

“Art and politics are both forces of nature. I’m an artist. I’m not a pop singer. It may not be part of the pop mainstream anymore, but I come from the moment in the ‘60s. I was an Elvis fan, Beatles fan, and then gravitated more toward acoustic music, because my dad wouldn’t let me have an electric guitar in the house. So, I listened to those Dylan records, and the Vietnam war was still going on. Politics was always going to be part of what I did,” Steve Earle said before letting out a sigh of frustration. “I thought we got past that mind-set a long time ago.

“The best way to write a political song – to write any song,” Earle said, “is to make it about what we have in common and not what drives us apart. I had a song on my first record about living on the road, separated from my son, ‘Little Rock ‘n’ Roller.’ The first conversation I ever had with Johnny Cash, he told me how much he loved that song. It was a really big deal to me, but two weeks later a truck driver came up to me and told me the same thing. What all three of us had in common is that we loved and missed our kids.”

Steve Earle finally left his Tennessee home, and the South, altogether, when the canyons dividing him and his neighbors grew prohibitively wide. In 2002, Earle wrote and released the courageous and compelling song “John Walker’s Blues,” an experimental folk song in which the narrator describes his journey from California to Afghanistan to fight alongside the Taliban. The mindless “controversy” that followed featured the unimaginative punditry asking Earle riveting questions like, “Is it too soon for a song like this?”

Earle expected the fallout, but he was shocked that some longtime friends and associates in Nashville broke off all communication. “That was it for me,” he confessed. “I just got tired of feeling like I was behind enemy lines. I wanted to live someplace where I could walk out my door and see a mixed-race, same-sex couple holding hands.”

Perhaps, Earle was searching for a sociological manifestation of the union he believes art can often officiate.

Art enlarges the imagination; through its injection of steroids in the muscle that is the brain, it elevates the possibility of perception. Throughout my conversation with Steve Earle, he continually repeated, “We let our culture slip away.” It is the catastrophic act of cultural negligence that creates most of problems, from personal unhappiness to political malfeasance, in America.

“How it happens is lefties allow for what little funding of the arts that did exist in this country to be reduced because they wanted their taxes lowered just like everybody else,” Earle coughed out with disgust. “I have liberal friends in New York who voted for two Republican mayors in a row, because they don’t get mugged at an ATM in the East Village.”

Earle’s depiction of askew political priorities is insightful and accurate, but it is a mere chalk outline of a large, bloated corpse of cultural decay. The decay becomes measurable with Earle’s remark, “If you think reality television is real, and Fox News is the news, you get President Donald Trump.”

The role for Steve Earle, or any troubadour, is debatable, as even he acknowledges. “What I do might become the equivalent of being a jazz musician or bluegrass player,” he predicted. “You can make a good living at it, but you’ll only get so far.”

It seemed that Earle’s status as subversive against the consistent simplification and obfuscation of complex truth in America might imbue his art with everlasting urgency. “I’m just doing what I can do and what I was taught to do,” Earle said with some ambivalence when I identified him as providing a countercultural service. “I know in some ways I’ve been left behind.”

Earle appeared as a cultural warrior who would refuse to go gently into the night, or die with a harness on his back, when he stormed the stage at the Old Town School of Folk Music.

He and the Dukes played every song from the outstanding new record, and over the course of two-and-a-half hours performed a wide range of selections from Earle’s rich career.

“You’re the Best Lover That I Ever Had” turned the elegant concert hall into a smoky blues room with Earle’s throaty delivery expressing the danger of carnal abandon. “Galway Girl” took the same setting, and turned it into an Irish barroom, lush green just down a stony road and pints of Guinness overflowing from the tap to the mug.

“Copperhead Road” rumbled through the fields of fire in Vietnam and the backwoods of rural America, while “Guitar Town” still captured the excitement of country stardom under the neon of Nashville.

Steve Earle’s description of his own song “City of Immigrants” – a tribute to multicultural and multiethnic America, as the “truth,” elicited an audience roar, but the most deafening ovation for a political moment transpired in the middle of Earle and the Duke’s intense rendition of “Hey Joe.”

Earle altered the lyrics, lifting his voice in a full shout to announce:

“Where you gonna run to now, where you gonna go?

I’m going way down south to Mexico

Before that asshole builds a goddamn wall…”

Steve Earle knows how to fight, and he can still carry himself with the bravado and brashness of a young Texan preparing to stare down the rednecks who tried to kick his ass before Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson managed to unite both the hippies and the hillbillies.

It does not seem like anger is the motivational force behind Earle’s steady movement. His disposition is one of idealism. “I object to my government executing people,” Earle said in a delineation of his philosophy of participatory politics. “Because in a democracy, the government is me, and I object to me executing people because of the damage it does to my spirit.”

Earle, with his unruly energy and creativity, is an animation of spirit. “I can’t text fast enough to be single in this day and age,” Earle said after looking at his buzzing phone during our discussion. Whether it is the foibles of modern courtship or the institutional failure of American governance, Earle’s art aspires to combat human despair with enlightened, but incautious, belief in better possibilities.

For his final performance of the night, he demonstrated the purity behind his self-classification as a creator of love songs.

“My biggest dream was not to become a songwriter or play a show like this,” he said while he softly played a melody on his acoustic guitar.

“My mom and dad met when they were kids, and they were together until my dad died just a few years ago. My biggest dream was to have that for me, with someone I love, in my own life. But we always managed to fuck it up. Sometimes it was her fault. Most times it was my fault. Now, I’m at the age where I have to face the possibility that it might not happen. But I still believe that there is someone out there for everybody, and that includes me.”

Without his band, alone underneath the spotlight with the blood of his heart dripping down his sleeve, he sang one of the new songs, “Girl on the Mountain.”

The tender, soul-shattering ballad, complete with the classic Earle guitar sound, describes a perfect, angelic woman who lives at the peak of the mountain, where stone meets the sky. Every night, he prays she will walk on down into his arms.

Wish I may, wish I might

On every star I see tonight

A million diamonds up above shine down on the one I love

The poets have a thousand tales to tell about love that didn’t work out well

Me, I sleep alright at night

Cause in my dreams I hold her tight

But the girl up on the mountain’s up there still

A few notes from Earle’s lonely guitar filled the quiet room. He looked up at the ceiling, and then lowered his head into the microphone with his eyes closed to release his last words of the night.

I love her now

I guess I always will

Walking onto the busy streets of Chicago, with the headlights of the passing cars speeding by, I believed in my heart that love can and will conquer all.

Shares