Among the millions of travelers heading out for the summer holidays, some are choosing an unlikely destination: a rusted bus on the edge of the Alaskan wilderness.

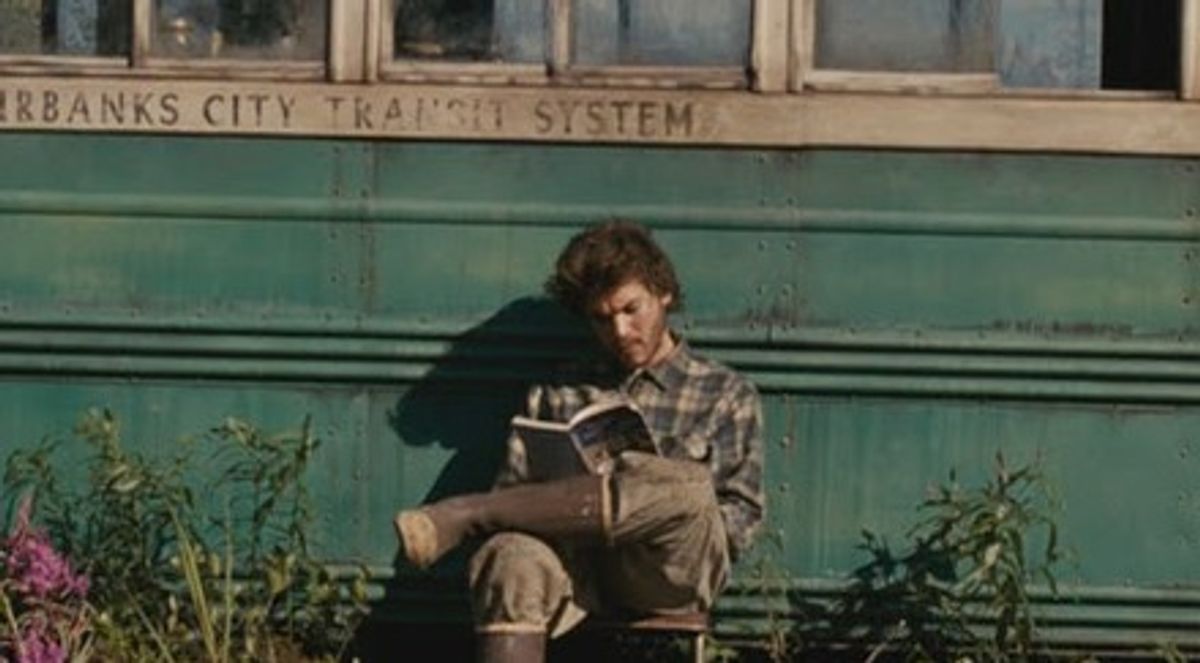

Fairbanks Bus 142 (aka the “magic bus”) is where the 24-year old Chris McCandless died in 1992. Well-educated and economically secure, McCandless rejected the materialism he saw in contemporary U.S. society. He set out to explore with only what he could carry, and ended up living off the Alaskan land for a few months before dying of starvation. His story was first told by writer and mountaineer Jon Krakauer in the book “Into the Wild,” and later made into a film directed by Sean Penn.

Since then, dozens of people every year seek to follow in McCandless’ footsteps. Finding inspiration in his mode of self-sufficiency, many head out to Alaska like secular pilgrims seeking to imitate a great saint from long ago, and to live more simply.

“Into the Wild” is not the only film to affect people in such a way. I have found many ways in which films around the world have motivated people to get up and travel to locations previously unknown — what I call “film-induced pilgrimage.” In these travels, tourists begin to look a lot like spiritual seekers.

Films and pilgrimage

Since the 1990s, researchers in tourism studies have been documenting the impact of cinema on travel decisions. Sue Beeton and Stefan Roesch, for example, have examined the work of tourist boards and conducted interviews with tourists motivated by films. The travelers’ reflections, they found, often contain deep-seated spiritual inklings. Tourists feel they’ve been somewhere important, “breathing the same air” as their cinematic heroes. They often bring back “relics” from their travels to show a place has made an impact — not unlike what occurs in more traditional religious pilgrimages, such as the Catholic shrine in Lourdes, France.

The uptick in travel to New Zealand after the release of the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy may be the most famous example of film-induced tourism.

Reports suggest tourism increased as much as 50 percent since the original film was released in 2001. And until recently the landing page of the New Zealand tourist board promoted the country itself as “Home of Middle-earth,” and continues to offer Middle-earth itineraries for visitors.

Yet it doesn’t take a mega-blockbuster to induce travelers. Many areas of the American Midwest were transformed by films such as “Field of Dreams,” “The Bridges of Madison County” and “Dances with Wolves.” Tens of thousands of tourists began traveling to small towns that previously saw no tourists at all. Reports show that places like Dyersville, Iowa, which was never anything more than a small farming town, was seeing over 50,000 people a year visit after the release of “Field of Dreams” in 1989.

Parallels with spiritual pilgrimage

As I describe in my book, “Religion and Film: Cinema and the Re-Creation of the World,” these film-induced travels can turn into something more than merely tourism: Distinctions between tourism and pilgrimage, on-screen reality and off-screen reality, and the secular and sacred grow blurry.

Robbie B.H. Goh, scholar at the National University of Singapore, too has found parallels between film tourism and spiritual pilgrimage. He calls it the “global fantasy industry,” a loose affiliation of the tourist industry, mass media (video games, television, film) and merchandising that motivates audiences to simulate fantasy narratives.

Even so, as Goh comes to understand tourists at “Lord of the Rings” sites, he finds that they do act like pilgrims with their ritualized acting out of movie scenes, heightened emotional states and buying of souvenirs that allow the pilgrims to bring part of the place back home.

Just as importantly, according to Goh, the difficulty of traveling through New Zealand’s rugged landscapes allows tourists to imaginatively imitate the ordeals of Frodo and the Hobbits in the story. Tourists become immersed in these spaces, which allows them to be immersed, in turn, in the heroic fantasy story itself.

There are stories of other films, other locations and other journeys as well: Tourists, for example, go to Rosslyn chapel in Scotland after “The Da Vinci Code,” visit Devil’s Tower, Wyoming after “Close Encounters” or imitate “Rocky” on the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Travelers to these various places have similar moods, motivations and spiritual and emotional experiences.

Rethinking pilgrimage

Some may hesitate here and ask whether these are “authentic” pilgrimages.

In the 1970s, anthropologists Edith and Victor Turner spearheaded the contemporary study of pilgrimage through publication of “Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture.” Since then, other scholars have questioned whether there really are useful distinctions between tourism and pilgrimage, and between the purely economic and the purely spiritual.

The thing is, pilgrimage and tourism are not really that far apart.

One of the defining evolutionary adaptations of early hominids was the emergence of strong foot bones and nonopposable big toes that enabled them to get up on two legs and walk great distances: out of Africa and into Europe, Asia and lands beyond.

Perhaps travel is hardwired into our species.

And maybe this is part of the renewed attraction of travel as we moderns grow restless with our always-online cultures, experiencing the world through tiny screens.

Film-induced pilgrimage takes the pixelized representation of being in a far-off land and makes it real again.

![]()

S. Brent Rodriguez-Plate, Visiting Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Hamilton College

Shares