Editor’s Note: Danny Goldberg is the modern version of the Renaissance Man. He has a long and colorful history as an activist, author, and influential music executive. Goldberg came of age at the height of the hippie era in 1967, experiencing the powerful and haunting mix of excitement, hope, experimentation and despair. He captures it all in vibrant detail and political nuance in his newest book, “In Search of the Lost Chord: 1967 and the Hippie Idea” (Akashic Books). AlterNet’s executive editor, Don Hazen, interviewed Goldberg in the offices of his company, Gold Village Entertainment, on July 12th.

Don Hazen: Let’s start by addressing what lessons we can learn from 1967, what analogies are applicable 50 years later. In the book [In Search of the Lost Chord] there is a lot about that classic split between the hippies and the radicals. And is that a Bernie/Hillary split? Is that split still with us? How do you look back 50 years and apply it today?

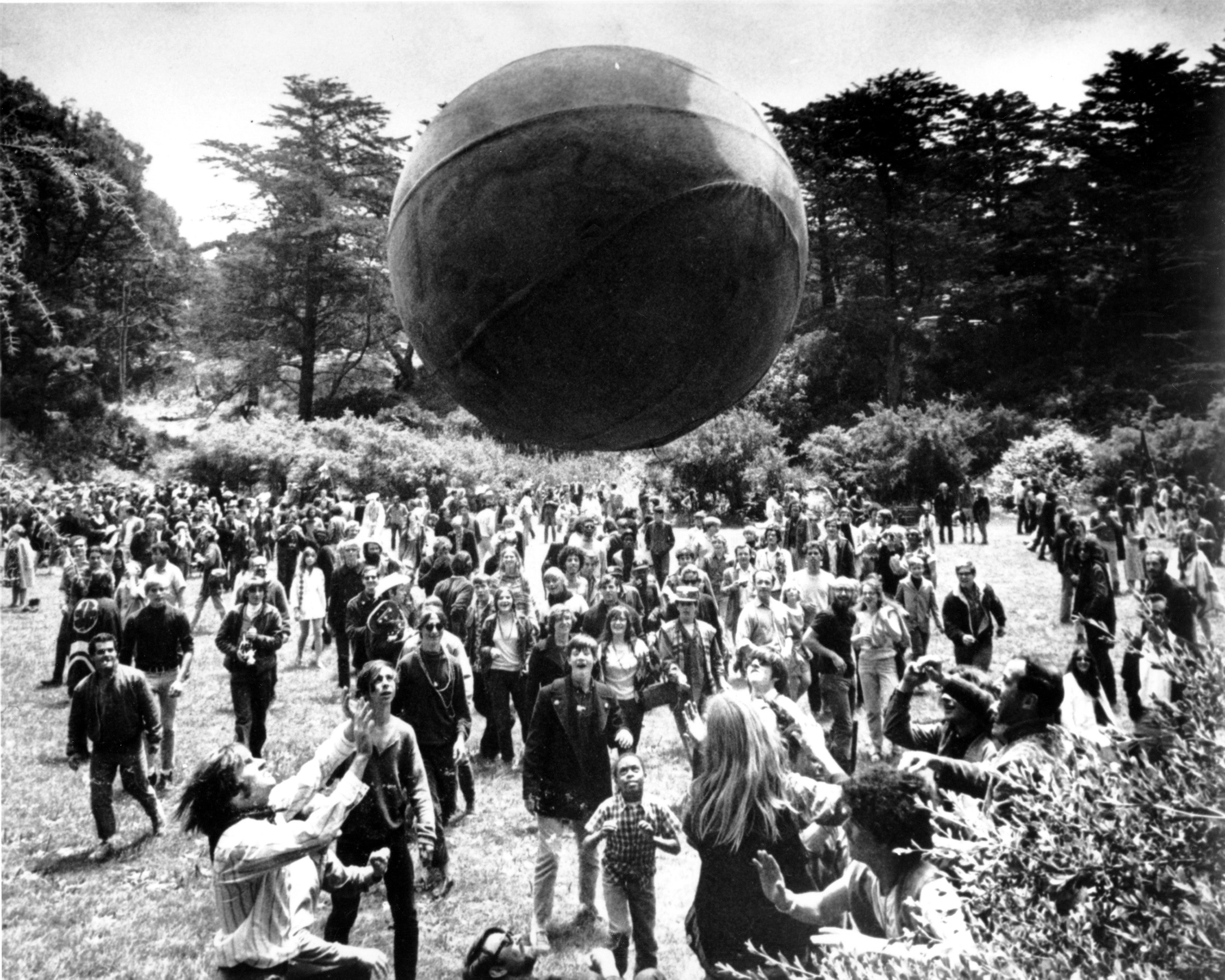

Danny Goldberg: Well, there are things to learn, to do, and things to learn not to do, from the ’60s. A major feature of the Be-In, in January 1967 that led to event of the Summer of Love, was that it was a “gathering of the tribes” to try to address that split.

There were also serious divides within the civil rights movement.

Stokely Carmichael and Adam Clayton Powell sometimes mocked Martin Luther King publicly and questioned his non-violent strategy. On the other hand, when Martin King came out against the war, the NAACP board voted 60-0 to condemn him for that position because they feared pissing off President Johnson. There were splits in the peace movement between the pacifists and non-pacifists; among those who focused on replacing LBJ with an anti-war Democrat there was bitter resentment between many of those who preferred Gene McCarthy and Bobby Kennedy supporters.

DH: And the Digger critique of Abbie Hoffman was what? He was not “lefty enough?”

DG: It was that the Diggers were committed to anonymity and Abbie was the opposite of that. There’s no question Abbie Hoffman was a self-promoter, but on the other hand he had the ability to popularize radical ideas in a way no one else could.

The Diggers saw themselves as the conscience of all these movements.

DH: And Peter Coyote was a Digger, right?

DG: Yes, Coyote was one of the thought leaders. The Diggers organized the free concerts near Haight-Ashbury. They made and gave free meals to hundreds of people. They ran a “free store.” They came from experimental theatre world and did a lot public displays that challenged conventional thinking.

They had a mimeograph machine, and distributed circulars in the neighborhood, and when the Black Panthers started in Oakland, the Diggers lent them the machine for the first three issues of their newspaper.

But they also had a self-righteousness that judged almost everyone else in the counterculture adversely. They had a commitment to ideals that were distinct from people that were more commercially minded, so hip capitalism was one of their targets. They also had a jaundiced view of Tim Leary. They were often confrontational with radical political groups that they felt were too mired in old ideology. In some ways, they were the forerunner of the most intolerant anarchists of the Occupy period. But they also had the creativity to create some of the purest expressions of countercultural idealism.

DH: Let’s step back for a second and ask you to explain how people should really understand the hippie idea and what, if any, ofitcould be applied to solving the problems that we are confronting today.

DG: The question I ask myself a lot, as I’ve been talking about the book, is: What difference does something that happened 50 years ago matter? Other than nostalgia (which I don’t think is a completely bad thing) the relevance depends on the extent that there are values that are not driven by the 24-hour news cycle or by who’s president, but endure from generation to generation, basic concepts about what it is to be a human being. To me, the hippie idea was a spiritual movement at its core, even though the word hippie and the external symbols like tie dye or long hair or hip language like “groovy” or “far out” or “cool, man,” soon became passé.

DH: Don’t forget the peace sign.

DG: Yes, the peace sign too — all of these things were quickly drained of meaning because of commercialization, the media magnifying glass, predators, etc. I understand why the punk generation that came along 10 or 15 years later had contempt for it, because they weren’t reacting to the experience I had; they were reacting to the cartoon version of it. I’m sure if I were of that generation, I would have been a punk also, because it was all about trying to seek integrity, authenticity, and meaning. But to me, the hippie moment was a critique of materialism. Ayn Rand’s philosophy was just as pernicious in the ’60s as it is today, or maybe the way to say it’s just as pernicious today as it was then.

DH: Is there any model of a counterculture theme or anti-materialistic vision that’s applicable today, anything like “back to the land”? Because the country is so split. The differences are just enormous. Even the way of thinking.

DG: The thing I keep hoping is that the meeting place is spirituality, because I do think that most people who identify as Christians are sincere about it. Even though many of the right-wing American leaders who exploit them seem quite removed from the spirit of the Sermon on the Mount, Pope Francis is a compelling and powerful moral and spiritual voice who, to me, evokes counterculture values as much as he does Catholic tradition. Some of the attitudes of conservative evangelicals are primarily tribal. But I think that the words of Jesus Christ are so powerful that they can have unintended effects; the idea of loving thy neighbor as thyself is essentially the same as hippie idea. In researching 1967, one thing that blew my mind was reading some of the speeches of Martin Luther King, and Bobby Kennedy; neither of whom, as far as I know, ever took LSD. They both wore suits and had short hair and didn’t identify as hippies in any way.

DH: No dashikis for Martin Luther King.

DG: And no love beads for Bobby Kennedy. . . But they came to the same meeting place in terms of the ideal that there’s more to life than just money. Kennedy gave this great speech about the Gross National Product measures everything except the things that are most important in life. And King, in sermon after sermon, talked about the inner world, of man as a spirit and as a soul. Of course he coupled this with an ethical code which required activism in an immoral world.

So it is my hope is that there is a critical mass of people who see themselves as being in different tribes, but who in their souls share some values that could create some kind of a moral clarity in the country.

The other big thing, I think, in terms of changing the politics of the country now, is to focus on young people, because that’s also a similarity with the ’60s. You’ve got this gigantic generation, the biggest generation since the Baby Boom generation, and more progressive. Those of us who were against the war were never a majority until way later when the whole country turned against the war by the mid-70s. But the proportion of younger people who voted for Bernie, the proportion of younger people who vote Democrat, is very, very high.

DH: Let’s go back to the spiritual theme. The heroes of your book are really Ram Dass and Allen Ginsberg. I’m interested in how you think that Allen Ginsberg and Ram Dass were able to carry that message, and whether it’s succeeded in beginning inside the culture, or the culture just went all materialist.

DG: I think it’s a mixed bag. One of the things about being older is knowing that I have more life behind me than in front of me, and it’s quite clear that the odds of all the problems of America or the Western world being solved in my lifetime is extremely low. The rapid success of the civil rights movement on certain issues and the explosive spread of hip images and rock and roll, I created a set of expectations regarding timing that were not realistic. But the fact that everything’s not perfect or close to perfect doesn’t mean that all the efforts to advance the species are a failure; it means that history is to be looked at in terms of hundreds or thousands of years, not just one generation. In terms of the individual lives, I think Ram Dass is exemplary. He’s been committed to service. The money from Be Here Now went to his foundation that he and Wavy Gravy among others set up that has helped cure blindness in millions of people in third world countries.

DH: I read a review of your book on the Be Here Now network. I never knew that existed.

DG: It’s a podcast network that is a spin-off that is associated with the foundation that is built up around Ram Dass and run by Raghu Markus. I do a podcast on it called “Rock And Roles.”

DH: Let’s talk about the riots, and segue from Martin Luther King to Detroit and to Newark and what a huge impact the uprisings had on the black community. We do not seem to have made much progress on race in this country. The riots of 1967 seem to have been a product of somewhat raised expectations from civil rights and the poverty program. Today, the black community has very little expectations. That might be a reason why white males are dying at a much higher rate than blacks and Latinomen,because their reality is more accepted.

DG: The scale dwarfs anything that’s happened since. In Detroit there were 43 dead, 1,189 injured, over 7,200 arrests, and more than 2,000 buildings destroyed. And much havoc in other cities as well.

Not everyone called them riots—they were called rebellions, revolts. They were usually triggered by police violence. But the tinder box of frustration, poverty, oppression was so great, and the raised expectations were followed by only marginal improvement especially in the North where the problems was “de facto” segregation that wasn’t fixed by the Civil Rights Bill. Before he was killed, King had become a much more radical and complicated thinker as the years went by and he saw the complexity of the legacy of racism.

DH: What else from the ’60s is applicable in the Trump era?

DG: Number one, ease up on tribalism on our side.

DH: Yeah, well, tribalism’s natural for corruption. And also for loyalty and protection.

DG: True. It’s incredibly seductive, because it feels good. It’s why people join gangs.

DH: Nepotism is one of the most powerful forces in the world. Taking care of your own, your family. Everyone protects their family, or else they’re thought of as having bad character.

DG: Taking care of your own family isn’t the problem. Doing it in a way that hurts other people’s families is what is immoral. The Mafia will claim you have no choice. The Mafia is the ultimate Ayn Rand entity.

DH: So, 1967 is the year that you picked, but ’68, ’69 and ’70 also were all huge years for me: ’69 was Woodstock, of course. ’70 was Kent State and Cambodia and the biggest student rebellion ever. It seems to me that the reverberations of ’67 just kept rolling along in different ways. And ofcoursethere’s Altamont versus Woodstock.

DG: Well, I think it’s about the balance, and that’s the conceit of the title, “In Search of the Lost Chord,” that there were these different notes and relationship to them, and it’s about the balance of the energies. Things got darker in ’68. with the assassinations of King and Kennedy. Another inflection point was the decline of Haight-Ashbury. There was a community in ’65 and ’66 and the beginning of ’67, it was a model of an alternative lifestyle that couldn’t survive the glare of the media. The media definitely killed it. There was actually a formal ceremony in Haight-Ashbury called Death of Hippie in October ’67. And the drugs got worse very quickly.

DH: The Brown acid.

DG: Yes, some of the LSD sold by less than idealistic dealers was mixed with speed. Pure speed, then as now brought out the worst in people. Heroin, then as now, destroyed lives. So even though shards of countercultural idealism cropped up in places well into the seventies, the peak was already in the rearview mirror. Even the purest kind of LSD had limits in its value to people. I’m someone who is very happy with my memories of LSD trips. I’ve never had a bad trip, thank God, but it became like seeing the same movie too many times. It’s been decades and I have no plans to take it again.

DH: Yeah, it doesn’t tell you how to figure things out.

DG: Yeah, at the end of the book, I quote Peter Coyote saying that LSD is like a helicopter that takes you to the top of the mountain, but then it brings you back down again, so if you actually want to live on the top of the mountain, it’s a lifetime of work to get up there, not a helicopter ride.

DH: But the hippie period trigger a lot of things such as “back to the land,” and the Grateful Dead, right?

DG: Absolutely. There are still reverberations from that period that continue to this day. Environmentalism had antecedents with people like Thoreau, but its explosion as a mass movement was the direct outgrowth of hippie culture. Many of the creators of a lot of the internet in the ’90s, including Steve Jobs, took psychedelics. On the political side, there is a direct line from the civil rights and anti-war movements to feminism, the gay rights movement, Code Pink, Occupy Wall Street, and many aspects of the Sanders campaign.

In the spiritual realm, in 1967, Richard Alpert, the fired Harvard professor who was Tim Leary’s protégé in popularizing LSD, went to India, met his guru Neem Karoli Baba, was renamed Ram Dass, wrote the book “Be Here Now,” a major catalyst of the New Age movement. And in 1967 the Beatles, who were the most famous musicians in the world, were introduced to meditation, which overnight went from being a word known primarily in monasteries and theology departments to being part of the language of pop culture.

DH: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, right?

DG: Yeah, the Maharishi was the first one that became a public figure when they visited him, but almost immediately afterwards, George Harrison and John Lennon became interested in the so-called Hare Krishna guru, Swami Bhaktivedanta.

And all this opened up a wellspring of a zillion different spiritual paths explored by people in the mass culture, some of the bogus but some real. The I Ching went from selling a couple of thousand copies a year to 50,000-100,000 a year, and was quoted in numerous rock lyrics. A lot of younger people were relieved that you don’t have to choose between the religion you were born into or purely secular materialism. There were lanes you could go down to try to integrate the idea of identifying yourself as a spirit without having to be enmeshed in the hierarchy of rules and structures that seemed irrelevant to a modern life. Some people found transcendence in mainstream religions but a lot of us didn’t find it there.

DH: As you talk about your book, is there a question no one asking you that you really wanted to answer? Is there something that you want the world to know about this book that you’re not getting out there?

DG: Well, the main thing about the book is its complexity. There were so many things happening all at the same time. It’s a mosaic of, a couple hundred pieces, and there were another couple of thousand that I couldn’t deal with because I didn’t have the time or the wisdom to do it. I feel guilty dumbing it down sometimes.

DH: Somebody in the book said that New York was always two years later, but you said by ’67 it had caught up. Is that really true?

DG: Ken Kesey said that to Tom Wolfe in “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.”

There was this sense of you had this magical thing that no one else had. When it was the province of universities and psychiatrists and people that were authorized to experiment with it, it was very limited. But once it was illegal in late 1966, it became easy to get. High school in New York, kids couldn’t get acid in 1964, but could in ’67.

DH: They had no Summer of Love in New York.

DG: I don’t know, man. It was nice to be young there then. That’s the year I graduated from high school.

There was a Be-In in Easter of ’67. There were these things that Bob Fass would organize, this Fly-In and sweeping up streets on the Lower East Side. It was a bit darker than the Bay Area, nut we had the peace and love thing going too for a minute.

DH: I was both a hippie and a radical and most of my hippie friends were political and most of my radical friends had disdain for drugs. And then there was, within SDS, therewassocial workers, the ones that cut their hair off and went to the factories and worked.

DG: But there were people who struggled to bridge the divide. Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and Paul Krassner — all had dual citizenship.

DH: Abbie Hoffman was one of our best political strategists. I traveled to Nicaragua with him and then I spent some with him in Zihuatanejo. But also I saw the dark side of him, too, which obviously led to his death. But he was amazing. He was manic depressive, yeah. And when he was manic, there was just no one, no one, who could compete with him as a speaker, as a thinker, strategist, as a performer.

DG: I think he’s a little underrated by history because the depression became more part of the story. Hoffman and Jerry Rubin and of course Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Brian Jones and Jim Morrison had tragically premature deaths. On the other hand, the people I dedicated the book to — Paul Krassner, Wavy Gravy, and Ram Dass — didn’t self-destruct, and continued to live righteous lives with real consistency about who they said they were as younger people as did Bob Dylan and Joan Baez and Peter Coyote and many others who are not famous but who are worthy role models.

So overall, it certainly is a mixed bag. I have a romantic view of it, but hopefully not a delusional view of it…

DH: Well, that’s a good way to stop. A romantic view of it, but not a delusional view of it.