It’s been over six months since Donald Trump became President of the United States, and the new administration and agencies have yet to get on their feet.

And for Louisiana in particular, the lack of federal aid and hurricane response leaders (which agencies are still scrambling for) has chipped a subtle crack between the state’s unwaveringly loyal congressional delegation and increasingly fatigued locals.

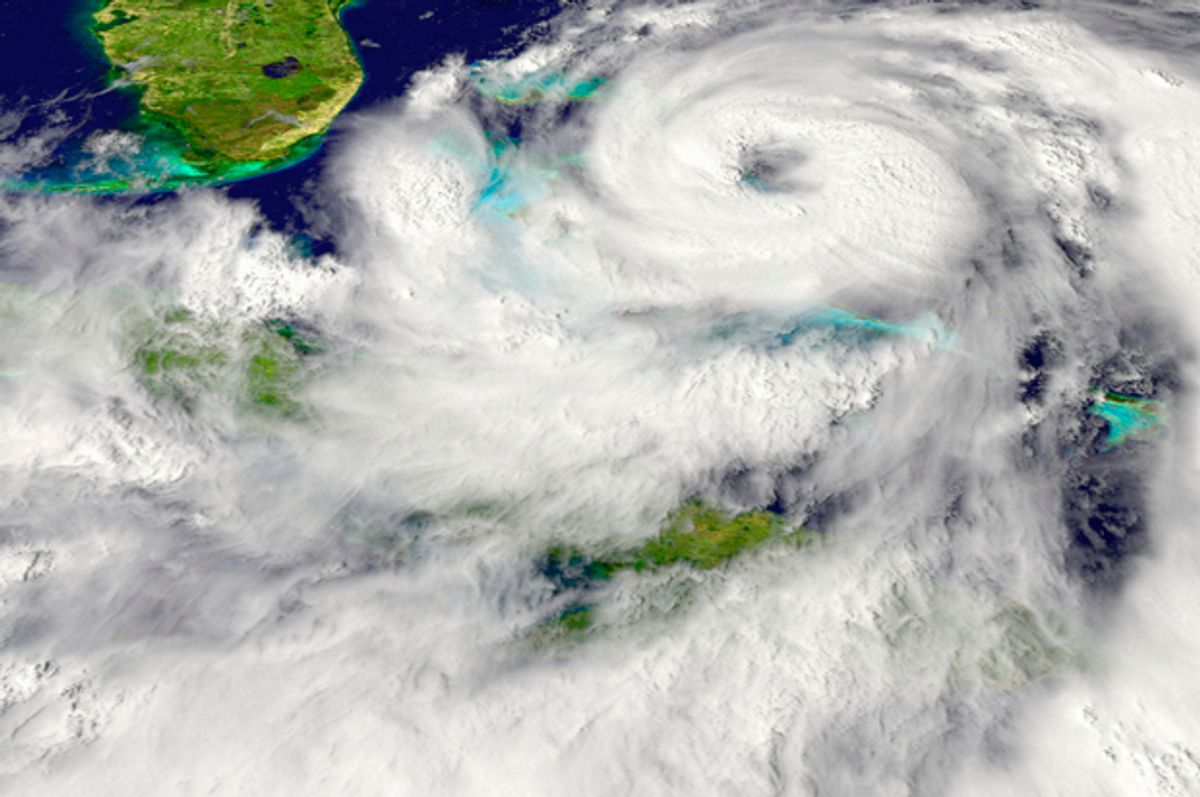

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) only swore in its permanent head, previous Alabama emergency response agency director Brock Long, in June -- just as hurricane season was underway and residents’ anxieties were elevating. But storms and flooding are in the back of Louisiana’s mind year-round; Hurricane Katrina’s shadow still looms, and many areas remain fragmented from last year’s historic floods that mainly destroyed low-income households and resulted in failing grades for FEMA in statewide polls. Officials predict an abnormally intense few months, with up to 19 named storms and five major hurricanes. This month, areas of New Orleans suffered nine inches of rain in a matter of hours due to failed drainage pumps, prompting school closures and a declarative state of emergency this week.

The unusually prolonged lack of key agency leaders has been a countrywide contention point in American politics. Long’s swearing in came 140 days into Trump’s presidency, which one state senator called “inexcusable.”

FEMA isn't the only disaster protection agency under pressure. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which directs weather forecasting and the National Hurricane Center, has also been without a permanent leader since Trump’s inauguration.

Some Republican lawmakers blame the lack of agency heads on Democrats for blocking presidential appointments — something freshman U.S. Rep. Mike Johnson,R-La., in June called “bitter partisan fights between every issue under the sun.”

Partisanship in natural disasters also infects federal-state relationships, particularly with Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, the outnumbered, lone Democratic governor in the Gulf South who said in May that Trump’s budget “turns a blind eye” to his state, in part because it pulls hurricane protection funds.

The governor petitioned for $3.6 billion in federal disaster aid a year ago after the August 2016 flood. He has only received $1.7 billion in disaster aid so far, and Rep. Ralph Abraham, R-La., blames Edwards for the slow progress.

Abraham said the rest will come once Louisiana shows it’s handling its first allocation, which the governor has just begun distributing to flood-affected homeowners this summer. The federal money became available to spend and the application process began in April -- months after it was originally asked for.

“We still have people from March [2016] living in hotel rooms, shelters [and] with relatives,” Abraham said in June. “They’ve been hurting.”

In fact, 57 out of Louisiana’s 64 parishes — 89 percent of the state population — is still in some sort of recovery from natural disasters since March 2016, according to the state’s Department of Children and Family Services. As of last week, about 1 percent of the Congressional appropriation was reportedly dispersed to affected residents.

Receiving federal aid in fragments is normal. But overall, Trump’s disaster aid package to Louisiana is unlike any the Louisiana governor can remember — mostly because it is the first that does not grant infrastructure aid, which would help prevent similar losses in future disasters. After Congressional appropriation, HUD has only given Louisiana enough disaster aid money so far for housing and an inadequate amount for infrastructure. The Trump budget proposal calls for eliminating future disaster aid funds, called Community Development Block Grants, entirely.

Louisiana did in July get a hefty gift -- hundreds of millions of dollars -- from FEMA for future flood prevention, which is separate from the infrastructure-starved aid package from Congress. The governor estimates the state needs more than three times as much of that money for future storm resiliency alone, which locals are still looking to their Washingtonian representatives to shore up. But FEMA programs are also slashed in Trump’s budget proposal, suffering hundreds of millions in cuts.

While the Trump administration has yet to see the kind of billion-dollar disaster that previous presidents have, Gov. Edwards and HUD Secretary Ben Carson met in person Tuesday to discuss removing certain federal regulations that slow down allocation. But some are not even looking to the federal government this hurricane season.

“A lot of times, the [federal] response is very lacking,” said state Sen. Bret Allain, R-Franklin, in June, as his state braced itself for another prayerful storm season under sea level. But the state takes pride in its resiliency: “If we don’t get help, we usually tend to take care of ourselves.”

At the time, Congressmen in Washington agreed. “If the Sheriff doesn’t come to work, guess what?” said Rep. Clay Higgins, R-La. “We still arrest people.”

This story has been updated to more accurately reflect the number manufactured housing units in East Baton Rouge.

Shares