On Aug. 16, representatives of the U.S., Canada and Mexico formally begin renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), an accord that has governed matters of trade and security on the continent for 23 years.

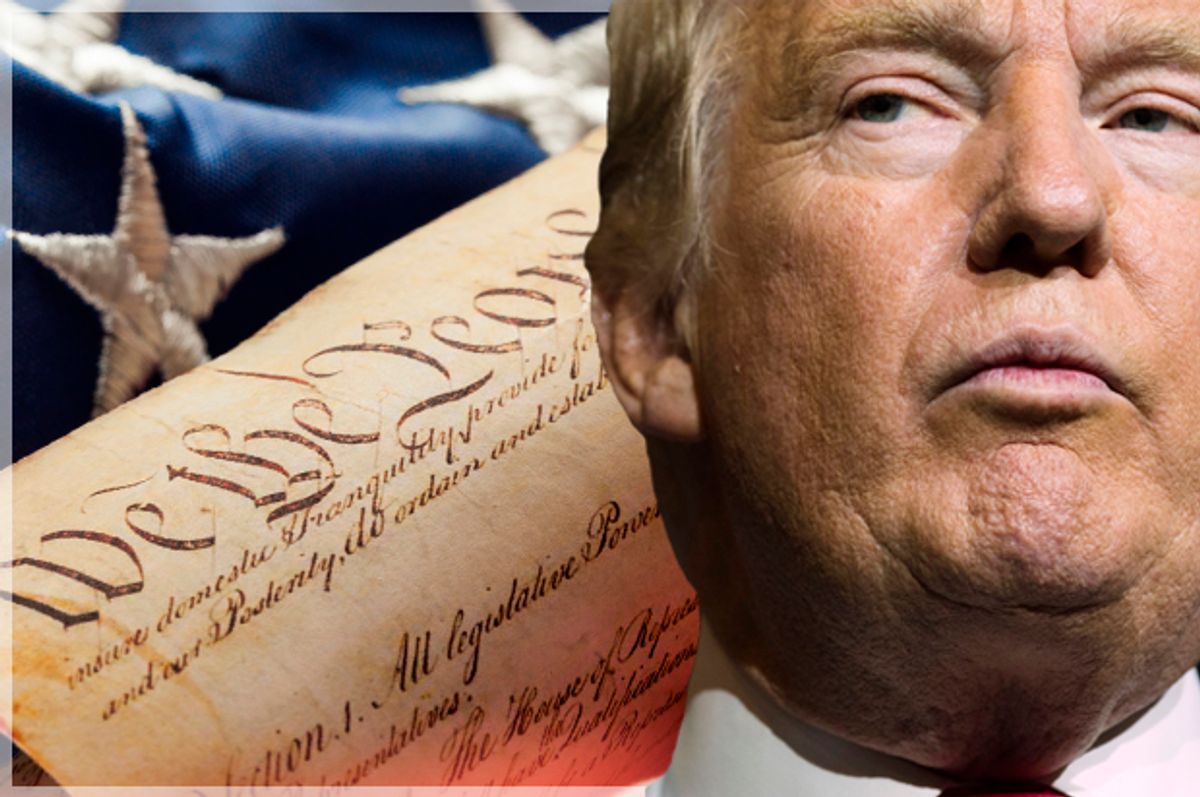

President Donald Trump has repeatedly threatened to withdraw the United States from NAFTA and similar trade agreements if other nations are unwilling to renegotiate to terms he likes.

Whether you agree with him or not, his threat to unilaterally back out of NAFTA and other trade deals on his hit list may be a hollow one for a simple reason: the U.S. Constitution.

Our country’s founding document places limits on a president’s ability to cease complying with the provisions of a U.S. trade agreement — absent congressional approval.

A perfect negotiating strategy

The U.S. recently released its objectives for renegotiating NAFTA. The threat to withdraw if those objectives are not met is an element of the U.S. negotiating strategy that deserves attention.

President Trump comes to the table after repeatedly declaring his intention to scrap NAFTA during the campaign and reportedly going as far as to prepare an executive order in April to begin withdrawal.

Despite the apparent change of heart, he insists that he stands prepared to terminate NAFTA if he is “unable to make a fair deal.”

Although NAFTA has been the main target of Trump’s displeasure, it’s not the only one.

The president said roughly the same thing about the U.S.-South Korea Free Trade Agreement (known as KORUS), declaring that “we are going to renegotiate that deal or terminate it.”

From a negotiating standpoint, threatening to withdraw makes perfect sense. If the United States isn’t willing to opt out of a trade deal, other nations have little incentive to offer a better one. The issue is murkier, however, from a legal perspective.

The Constitution is oddly silent on the question of how the United States ends its international commitments. Most foreign relations lawyers believe that the president has the authority to withdraw from treaties without congressional consent, and presidents of both parties have acted on that basis.

But trade agreements are different from, say, defense agreements, where the courts have declined to restrain the president’s unilateral termination power. The Constitution plainly assigns power over the policy areas covered by trade agreements — foreign trade and tariffs (taxes levied on imported goods) — to Congress, not the president.

Constitutional limits

Article I, Sec. 8 of the Constitution provides that “Congress shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises” and “regulate commerce with foreign Nations.” Congress uses these powers to pass legislation that translates each trade agreement into federal law.

To be sure, since the 1930s Congress has used these laws to delegate responsibility for setting tariffs to the president. The NAFTA Implementation Act, for example, is a federal law that grants the president the authority to set tariffs in accordance with the terms of NAFTA.

But even if the United States were no longer bound by NAFTA as an international agreement, the NAFTA Implementation Act would remain on the books unless Congress repealed it. The president would thus likely still be bound by federal law to set tariffs that complied with NAFTA.

If NAFTA ceased to exist, wouldn’t the legislation that assumes NAFTA is in place also lose its force? The legislation implementing more recent free trade agreements says as much explicitly. For example, the statute that implements KORUS states that it “shall cease to have effect” on the date that KORUS itself terminates.

The thing is, the Supreme Court has held this kind of provision unconstitutional. In Clinton v. New York, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress cannot delegate to the president the authority to unilaterally repeal a statute. That case struck down the Line Item Veto Act, which allowed the president sign a bill into law but then unilaterally “cancel” individual spending measures within the new law.

The same logic should apply to trade agreements. The president may very well be able to withdraw from international agreements like NAFTA and KORUS without further congressional authorization. But the president cannot constitutionally ignore or cancel the domestic laws passed by Congress simply by withdrawing from an international commitment.

In other words, even if the United States leaves NAFTA, the president will still be bound to implement the agreement’s rules on the terms dictated by Congress until Congress says otherwise.

Doubts on delegation

President Trump might have another problem too.

The Constitution explicitly gives Congress the power to set tariffs and govern foreign commerce. Congress, in turn, usually delegates this authority to set tariff rates to the president. The constitutional “nondelegation doctrine,” however, requires that Congress establish standards to guide the president’s choices when he exercises delegated authority.

A growing number of judges and commentators have urged the courts to more strictly enforce the nondelegation doctrine. Most notably, President Trump’s appointee to the Supreme Court, Neil Gorsuch (for whom, in full disclosure, I clerked), has expressed skepticism about the breadth of some congressional delegations.

Requiring that tariffs (or other trade policies) be set in accordance with trade agreements like NAFTA satisfies the nondelegation doctrine. But if the president can evade the standards Congress has imposed by withdrawing from trade agreements, then arguably Congress has violated the Constitution by failing to sufficiently constrain the president’s authority.

In other words, laws like the NAFTA Implementation Act that implement trade agreements could be unconstitutional if the president were free to ignore them. To avoid this constitutional problem, courts would likely require that Congress act before the president can cease complying with the laws that implement U.S. trade agreements.

A better strategy

President Trump, of course, has other tools at his disposal to increase pressure on our trading partners to renegotiate trade deals.

He can use the rules and institutions of trade agreements themselves to challenge unlawful trade practices, as the administration has already announced it intends to do at the World Trade Organization.

But if he is serious about the threat of withdrawal, the president’s best strategy may be to seek legislation authorizing him to retaliate against our trading partners if negotiations are not successful.

That legislation may be difficult to get through a Congress that is generally pro-free trade. But elements in both parties seem to have an appetite for rethinking what trade agreements should look like. And the president has defied expectations before.

Tim Meyer, Professor of Law, Vanderbilt University

![]()

Shares