Alexandria, Egypt’s second city, was once a cosmopolitan place. Nestled in the eastern Mediterranean at the corner of Africa and the Levant, it attracted large numbers of Greeks, Italians, European Jews, Lebanese and others. It was a hub of many languages and cultures in the polyglot society that was Egypt in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th. Squint hard enough and the remnants of that era comes into view, but they remain a blur. Alexandria is a ramshackle sprawl now, the unfortunate result of poor or nonexistent urban planning, Egypt’s population growth and massive corruption. In an ironic twist, the city has also become an Islamist stronghold over the last four decades.

There is, of course, a lot of hagiography about Egypt during its so-called liberal period — roughly the years following World War I through the 1940s. Egypt was never as progressive as it is sometimes portrayed. Even the wistful memoirs about life in Alexandria and Cairo in the mid-20th century portray a rather more complicated reality of foreign occupation, a feudal-like economic system, discrimination and religious zealotry. Fascism, or the tactics of fascists, also appealed to some. Still, in many ways Egypt during those years was a more tolerant, open and dynamic society. At the elite level, at least, people from all walks of life, backgrounds and experience were part of the social, political, intellectual, cultural and economic fabric of society.

It has been hard to make that case for the better part of the last 60 years, however. What happened to Egypt was the development of a powerful set of ideas related to populism, nationalism and religious fundamentalism that venal leaders and political entrepreneurs stoked for their own parochial interests. It is a story that remains largely unknown outside the relatively small world of specialists on Egyptian politics and history, but it is unexpectedly relevant to the political dilemmas and conflicts currently roiling the United States. Even accounting for the vast differences in history, culture, political systems and economic development between the two countries, Egypt’s tale is a cautionary one for the United States today. At a level of abstraction, that toxic brew of populist, nationalist, religious politics that combined with cynicism to cause Egypt’s regression is present in American society too.

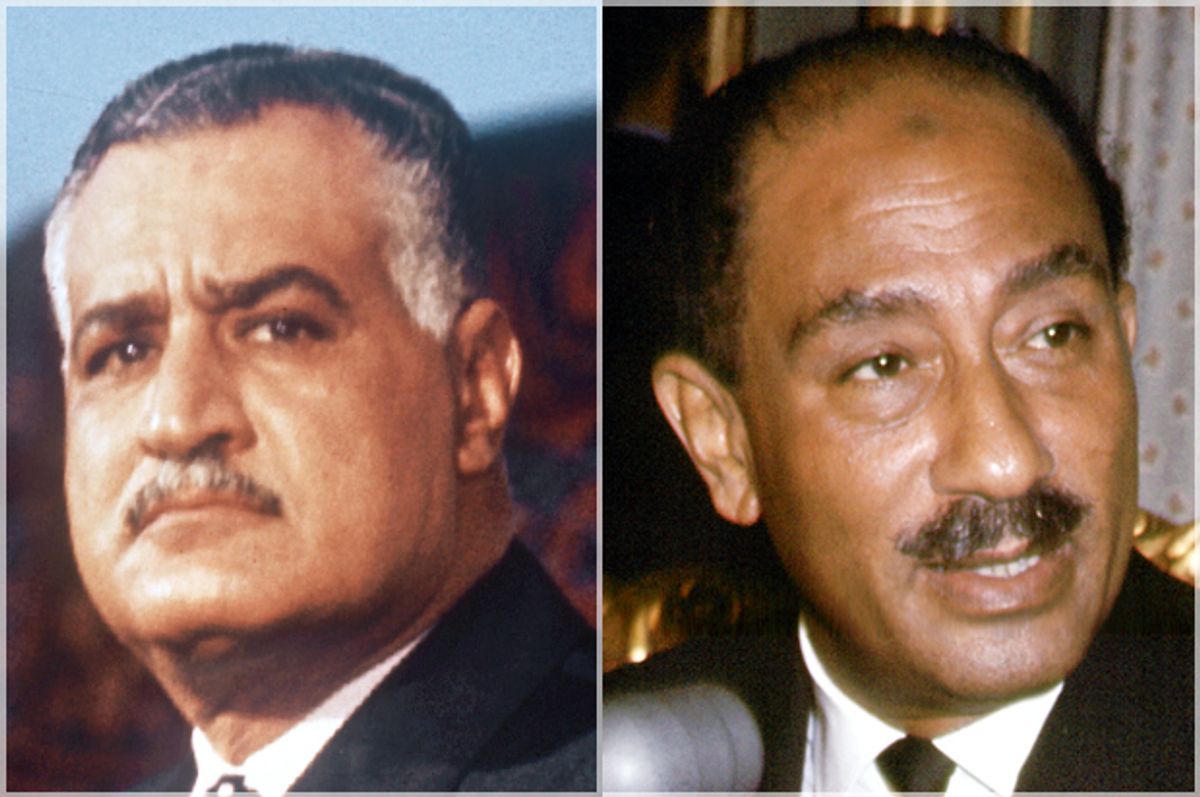

When the Free Officers seized control of Egypt in a coup in the early morning of July 23, 1952, they had little idea about how to govern and what exactly they stood for. Then Lieutenant Colonel Anwar al-Sadat, who announced the takeover on Egyptian radio, emphasized the corruption and the pernicious effects of the continuing British occupation of the country. These relatively junior commanders, among whom Gamal Abdel Nasser was first among equals, initially stated that they merely sought “reform” but in time declared that they would tear down the political system and build a new regime in which the officers would ostensibly wield power. This project, particularly the part that gave the military the preeminent place in the new political order, produced a variety of opponents ranging from liberals and communists to Muslim Brothers and students of all political hues and stripes.

The officers used a lot of force to impose their will on the opponents of their new regime, but force alone is both insufficient and costly. They needed a political strategy as well, and Nasser soon discovered that populism was an effective means of securing the new system and his own power. In this he had a lot of material with which to work. The British had occupied Egypt since 1882 and ruled through a corrupt monarchy and powerless governments. During this period there were revolts against this unfortunate situation and growing resentment toward elites who presided over a system that perpetuated massive inequality. Nasser thus emphasized the pernicious influence of external powers and thus a distrust of foreigners, the previously rigged and corrupt political system, and the new leadership’s intention to uplift the great reservoir of average Egyptians. He and his fellow Free Officers played on their ostensibly humble origins, though most of the dozen or so of them were from middle-class or upper-middle-class origins.

In July 1956, Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal — which had been under British control since 1875 when Egypt’s ruler, Khedive Ismail, was forced to sell the country’s shares to settle outstanding debts to European banks — promising to use the proceeds to, well, make Egypt great again. The move made sense, given that foreigners were the ones benefiting from Egypt's crucial waterway, and it sealed Nasser’s reputation as a nationalist par excellence; appropriating the canal was and remains a central element of Egypt’s national mythology.

Nasser also built a metaphorical wall. The weight assigned to Egyptian-ness and Arabism at the time clearly defined who belonged to the community and who did not, which increased political, social and economic pressure on people who thought of themselves as thoroughly Egyptian, but were nevertheless outsiders in Egypt’s nationalist discourse. At the same time, separate waves of nationalization dispossessed owners of capital of their property, forcing the exodus of Egyptians of Greek, Italian and French origin from the country, including most of Egypt’s remaining Jews who had not already fled to Israel or Europe. In the contemporary United States, what it means to be an American is being redefined by debates about immigration that are suffused with ideas that give pride of place to Caucasians and Christians, impelling people who do not meet these criteria to leave and for those who don’t leave to take their chances with Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers.

After Nasser’s death in 1970, Sadat came to power. He is lionized in the West for his visit to Jerusalem in November 1977 that led to the Camp David Accords and Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel, as well as for the infitah, or economic opening, that led to the full-fledged return of private enterprise in Egypt. Yet Sadat also pursued a political strategy that may be instructive for Americans at this moment.

To outmaneuver his rivals and secure his position as president, Sadat established a reciprocal relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood in which they were afforded opportunities to advance their moralizing agenda, which was authoritarian and intolerant, in exchange for political support. The Brothers were never as fringe as the white supremacists and white nationalists that President Donald J. Trump alternately winked at and supported throughout his campaign and thus far in his presidency, but the reasons for his ties to them are strikingly similar to Sadat’s succor to the Brotherhood.

In time, the Egyptian leader’s dalliance with Islamism contributed to his undoing — the “Believer President” could never live up to his own religious commitments and the expectations of the Brothers — and to Egypt’s as well. Over the following decades the Brothers were able to frame the terms of debate on issues as diverse as the arts, literature, education, foreign policy and identity. Tweak the language and the problem the United States is facing comes into view.

Religious fundamentalism, although it's nothing new in America, has become a more prominent part of mainstream discourse. President Trump’s spiritual adviser, Paula White, recently declared that to oppose him was “fighting the hand of God.” She faced a storm of criticism from theologians and others, but not from a political class fearful of a backlash from its religious base. In Egypt, leaders were often forced to accommodate the demands of Islamists, no matter how outrageous, for precisely the same reasons. Islamists’ uncompromising positions on what was acceptable and what was beyond the pale necessarily dulled a once dynamic society and produced an inconclusive culture war that further sapped the energy of a country with a wealth of human capital. Is this what Americans want?

There are good reasons for Egyptians to admire Nasser and Sadat, though the latter remains significantly less popular. The Nasser years were a moment of empowerment and the Sadat period was a time of (partial) victory and the (partial) restoration of Egypt’s sovereignty. These events were supposed to recapture Egypt’s lost greatness, worthy of a society that is the inheritor of the Pharaonic civilization. Yet in their parochial politics, they manipulated identities, whipped up nationalism and sowed division. The result is an Egypt that has lurched dysfunctionally from one crisis to the next, unable to solve its problems because society has become so deeply polarized, mistrust and cynicism reign, and violence is an ever-present possibility. Unless Americans are careful, Egypt’s present reality could be our country’s future.

Shares