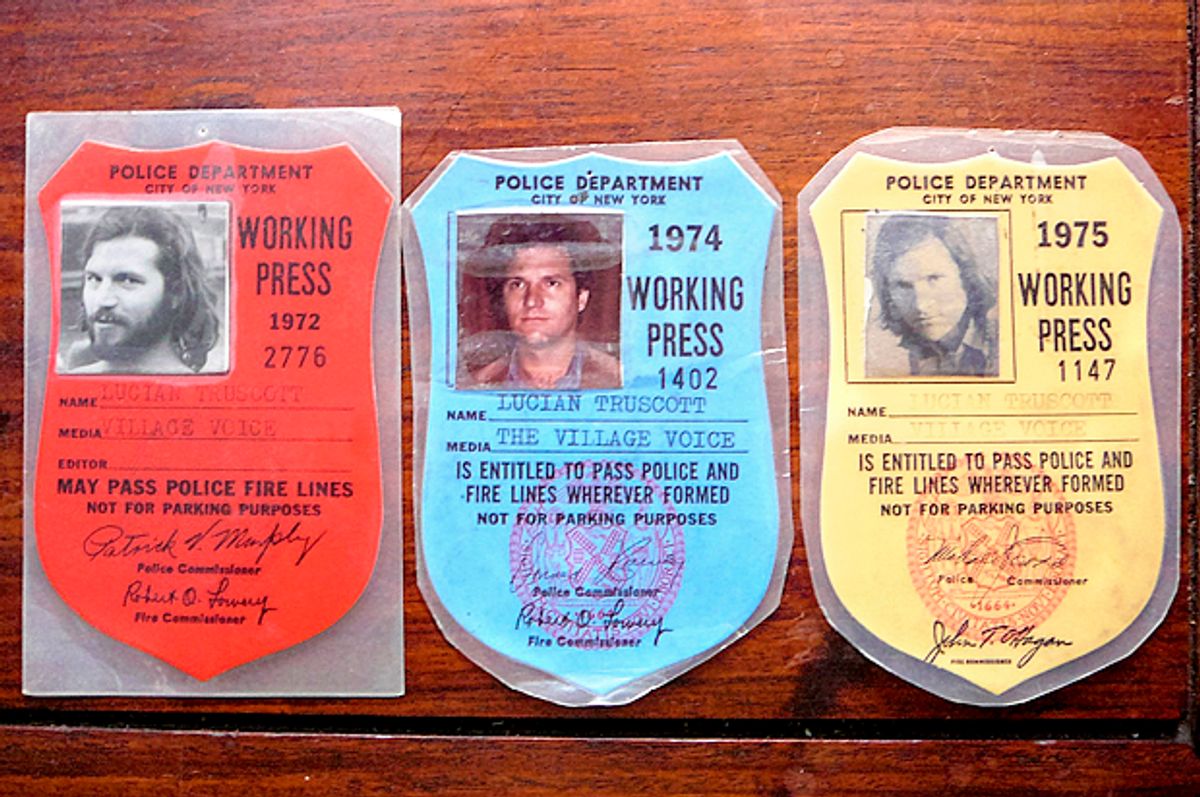

The sad news last week that the venerable Village Voice will cease its newsprint edition and become an on-line only publication, not unlike Salon, brought back some memories. I got my start at the Village Voice more than 50 years ago, and I’ve never told that story, so just for you, just this one time, here it is.

The year was 1964. My friend Fritz Lash and I were riding our 10-speed bikes across the country. I was 17, Fritz was 16, and while 10-speed bikes were brand new on the American scene, the idea of turning a couple of teenagers loose like that for a summer wasn’t. My parents started sending my brother Frank and me across the country on Greyhound buses when I was 12 and Frank was 10. Fritz took a Greyhound from Kansas to meet up in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where we began our journey by first riding east to New York City. The World's Fair beckoned.

Fritz and I rode through eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey and took a little steel truss bridge over to the Fresh Kills area of Staten Island, rode across the island, took the ferry to Manhattan and rode uptown to 32nd Street, where we scored two single rooms at the Y for 75 cents a night. The Worlds Fair was a bust – insane crowds, oppressive heat and a blazing sun, absolutely no shade, and everything cost five times what it did a subway ride away in the city. So we gave up on the mess in Flushing and rode the subway to the Village. Folksingers in pass-the-basket coffeehouses, street vendors selling sausage sandwiches for a quarter, crowds of babes in long hair and tight skirts and leather sandals, each one more mysterious looking than the last.

And over there at the newsstand, a paper that told you all about it — The Village Voice. A dime, I think. Maybe it was 15 cents. On the cover a Fred McDarrah photograph of Joe Cino standing in the middle of his burned out coffeehouse at 31 Cornelia Street, where people were putting on plays as part of something called off-off Broadway. The story said a committee had already been formed to take up a collection to help Joe rebuild. There was going to be a fundraiser for him, as I recall, at someplace called the Judson Church. Elsewhere in the paper there were ads for clubs on Bleecker and McDougal, featuring singers like Carolyn Hester and Tom Paxton and Fred Neil and Odetta and Bob Dylan.

I read that copy of the Voice cover to cover and stuck it in one of the saddlebags on my bike as we headed west. It stayed there for the next two month, and as we were camping out along the roadside in our jungle hammocks, I would take out the Voice and re-read the story on Joe Cino and read the theater reviews by Michael Smith and the crazy Village goings-on chronicled in Howard Smith’s “Scenes” column. I took that copy of the Voice home with me at the end of the summer, and it sat on top of my dresser throughout my senior year in high school. When I got to West Point in 1965, I subscribed to the Voice and read it cover to cover every week, and followed its recommendations to go to places like the Five Spot on St. Marks Place and the Café au Go-Go, to listen to music on the rare occasions we got time off to go down to the city.

I’ve given a lot of thought over the years to why I was so attracted to a gritty little newsweekly from Greenwich Village that was just beginning to cover — if not help to create — what was just becoming known as the “counterculture.” I think it goes back to that first issue I bought with Joe Cino on the cover. There was a real community behind that story — the community that would help Joe rebuild his off-off Broadway venue where playwrights like John Guare, Tom Eyen, Sam Shepard and Lanford Wilson would get their starts. What an exciting scene! Virtually everything was not just new, but brand new — the theater, the music, the dance, the clothes, the hair — oh, yes, the hair! — and the politics. The Voice would repeatedly beat back something called the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have run across Canal Street, devastating Little Italy and Chinatown and most of what would become SoHo, and the Voice backed a little known local politician named Ed Koch (who was also the Voice’s lawyer) in defeating the last Tammany Hall boss, Carmine DeSapio for district leader of Greenwich Village, giving life to reform politics in New York. It’s hard for me now, sitting at this keyboard, to describe how exciting all of this was — yes, even to a cadet at West Point. Things had begun to change in the country, and much of it was starting right there in New York City, and the newspaper covering the change was the Village Voice.

The Voice was filled with writers like Richard Goldstein, who virtually created rock criticism in his column “Pop Eye”; Ellen Frankfort and Susan Brownmiller and Ellen Willis and Vivian Gornick, and Claudia Dreifus who helped create a modern feminism in its pages long before there was MS magazine; Ron Rosenbaum, whose groundbreaking peregrinations through pop culture are now taught in journalism schools; Jack Newfield, who could give you an investigative piece on the “ten worst” of anything, from landlords to judges to city commissioners; Phil Tracy, who excavated Albany and returned New York State corruption to the front pages; and city editor Mary Nichols, whose column “Runnin’ Scared” had every pol and gangster in the city running scared every Wednesday for years.

Naturally, me being me, I had something to say about all of this, and the Voice had a place for me to say it: the letters to the editor column. I sat down at my desk in New South Barracks at West Point in 1966 and wrote my first letter to the editor, an exceedingly well-considered criticism of a figure who was just beginning to make his mark on the scene in the Village. “Abbie Hoffman is an asshole,” I opined, signing my name Lucian K. Truscott IV, West Point. Well, the Voice saw fit to run that letter at the top of its letters column, and the following week, they received (I would later learn) no less than 37 replies to my letter, from such august figures as Dwight MacDonald, Aryeh Neier, Paul Goodman, and as I recall, Abbie himself, who had something very funny to say about receiving such high praise from West Point. I fired off a reply to their replies, and we were off. I wrote many letters to the editor, most of them quite conservative — both my father and my brother were serving in Vietnam at the time, and I was quite eager for us to “win” that war and for them to come home. I was roundly attacked, of course, and I attacked back. For several years, I had what amounted to a column in the letters column of the Village Voice.

In December of 1967, I received in the mail at West Point an invitation to the Village Voice Christmas party in the Village. It was the weekend of the Army-Navy game, and I had leave for that night, so a friend and I made our way down to the Village in our Dress Gray uniforms and knocked on the door of a brownstone apartment on West 10th Street. I could hear a party going on in there on the other side of the door, but there was no answer, so I just grabbed the knob and opened it. The door hit Bob Dylan’s arm — or it might have been Phil Ochs’, I can’t remember, it was that kind of party -- causing him to spill his drink on the front of Mayor Lindsay’s suit.

It took me about an hour to work my way to a back room in the apartment where someone pointed out the three founders of the Village Voice standing in the corner with their backs to a bookcase. I recognized Norman Mailer of course, but I didn’t know the other two, so I walked up and introduced myself to a man with graying hair and a sly smile on his face and thanked him for inviting me. It turned out to be the Voice’s editor. “I’m Dan Wolf,” he said. “Thank you for coming. Oh, by the way, I was an infantryman in the Pacific during the war.” He introduced me to the man standing next to him. “I’m Ed Fancher,” he said. “I’m the Voice’s publisher. I served under your grandfather in the 10th Mountain Division in northern Italy when he commanded the 5th Army.” He introduced me to Mailer, who told me that in fact, he had also been a rifleman during the war in the Pacific. The Village Voice, that leftist rag in Greenwich Village, was owned by three former infantrymen, all veterans of World War II. “So that’s why you’ve been running my letters!” I said. Wolf laughed. No, that wasn’t the reason. They liked the way my letters stirred things up in the Voice. As it turned out, the letters column was the most read page in the whole paper. Having me in it was good for circulation.

After that night, I started coming down to New York every chance I got, and when I could make it on Fridays, I would get myself over to the Voice’s old office on the corner of Christopher and 7th Avenue in the late afternoon and take a chair next to Wolf’s desk and sit there and wait as the Village Voice writers would arrive to hand in their copy. In would come Jack Newfield and Michael Harrington and Joe Flaherty and Joel Oppenheimer and Pete Hamill and Andrew Sarris and Molly Haskell and Jill Johnston and Deborah Jowitt and Lucy Komisar and Vivian Gornick and so many others. If they stuck around, Wolf would pour Scotch into teeny little paper cups and pass them around, and everybody would sit around, and Flaherty would tell hilarious stories, and everyone would complain that their stories weren’t getting enough play. This would go on until about 6:30/7:00, and then it was over, because everyone had some place to go on a Friday night — to the theater to see a new play by Lanford Wilson, to a new movie by Goddard, to the Cafe Au Go Go to see Tim Buckley and bands like the Grateful Dead, to Steve Paul's Scene to see the Doors and Sha Na Na and Slim Harpo, to the Fillmore East to see the Allman Brothers and Janis. One Sunday in 1968, after just such a Friday afternoon soiree in Wolf’s office, I slipped an envelope containing a rather long letter to the editor under the front door of the Voice, and on Wednesday, they ran it on the front page and paid me $80. Just like that, I was a writer.

A night or two before I slipped that envelope under the door was Christmas eve, and I went to St. Marks in the Bowery to listen to Ed Sanders and Allen Ginsberg, and Gregory Corso and others read poetry. Jimi Hendrix came in and sat down next to me, and we spent the next two hours listening to poetry and talking. I introduced him to Ed and Allen, and they introduced him to Gregory, and it turned out that Jimi was a great admirer of all three of them, and they had a lot of stuff in common. Jimi had been in the 101st Airborne Division. I was a cadet at West Point who would be commissioned in the Infantry six months hence. We had some stuff in common, too. It was 1968 in the Village, after all. Things were happening everywhere, every night. You never knew who you’d see at a club, who you’d run into on the street, who you’d read in the Village Voice. Even a cadet from West Point.

Now the Voice is going to cease publication in print. To say it's the end of an era doesn't do justice to either the word "end" or "era." Everyone who’s worked for the Voice over the years has had an era, of course. I just hope this one doesn’t end. Long may the Voice live online! After all, you never know who you’ll find. Maybe even a crotchety old veteran who got his start there 50 years ago.

Shares