With the intense debate happening about the removal of the Confederate statues across America, pro-Confederate memorialists, including our president, have been obsessed with invoking the argument that ‘we are tearing down our history.’ It’s an ironic statement given perhaps no country ever has been more bent on silencing its own history than the United States.

As journalist Wesley Lowery tweeted after Charlottesville, “I don’t know anyone who wants Confederate monuments gone who doesn’t also want *more* public education about slavery.”

To combat America’s general reticence when it comes to acknowledging its racial foundation and the way those racial caste systems morphed and evolved, attorney Bryan Stevenson, through his organization, Equal Justice Initiative, will open a new museum, “From enslavement to Mass Incarceration”, in 2018.

The African American history museum emerged from a report EJI published in 2013 titled “Slavery in America.” EJI wrote on their website about the museum’s motivations:

This museum is designed to change the way we think about race in America. The United States has done very little to acknowledge the legacy of genocide of Native Americans, enslavement of black people, lynching, and racial segregation. As a result, racial disparities continue to burden people of color; the criminal justice system is infected with racial bias; and a presumption of dangerousness and guilt has led to mass incarceration, excessive punishment, and police violence against young people of color.

The museum is scheduled to open in April, EJI said, and on the land of a former slave warehouse (where EJI resides) in Montgomery, Alabama. “The museum’s location at the site of an Alabama slave depot gives it a powerful sense of place that visitors will feel when they enter,” EJI explained on their website.

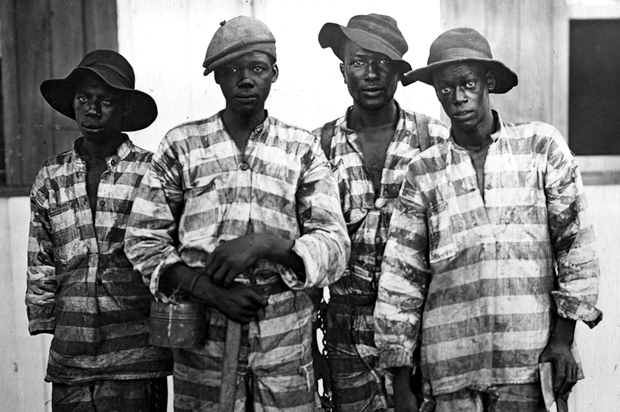

In the last few years, there has been some progress, mostly on the parts of black creatives, to build and create spaces dedicated to addressing the United State’s history of enslavement and racial hierarchy. The National Museum of African American History and Culture that opened to the public in 2016 and filmmaker Ava Duvernay’s “13th,” a documentary that traces the evolution of enslaving black bodies from convict leasing to mass incarceration, are both groundbreaking examples.

“What’s interesting to me is that it’s been only in the last few years that we’ve begun to even talk about slavery in a meaningful way,” Stevenson told artnet News. “That we are only now beginning to see significant cultural institutions emerge to address that legacy is actually revealing about how committed we have been to not talking about this. We’re just getting started, frankly.”

Alabama, where EJI operates, has the highest death-penalty rate per capita in the nation and 51 percent of defendants sentenced to death are black. The state’s legacy of slavery is also substantial, and in Montgomery alone, there are 59 markers and monuments to the Confederacy, Stevenson told artnet News.

After EJI published their “Slavery in America” report, they proposed placing markers at sites of slave warehouses and marketplaces, but local authorities thought it might be “too controversial,” Stevenson told artnet News.

Of the museum’s emergence, “I don’t think there’s any question that after 150 years of silence, it’s going to be provocative to see this legacy made plain,” Stevenson said.

But Stevenson hopes that with the creation of the new museum, America can emulate countries like South Africa, Rwanda and Germany, who all have cultural institutions that address their violent histories. “While I’m grateful to now have the NMAAHC [National Museum of African American History and Culture], and I’m pleased we have the National Civil Rights Museum,” Stevenson said. “We don’t have narrative museums that tell the story of our history in a way that moves you from point A to point B.”