Already President Trump and the Democrats are trading clichés in the opening skirmishes over Trump’s tax reform proposals. Yet both are missing the bigger reality of who are the economy’s winners and losers — a pattern that’s only grown over recent decades.

Trump, of course, wants to cut corporate taxes, and consolidate and lower rates for income tax brackets, among other things. All one really needs to know there is that he is dubiously assuming the savings for businesses will “trickle down” to employees in jobs and wages. Leading Democrats, in response, are being misleading in a different way.

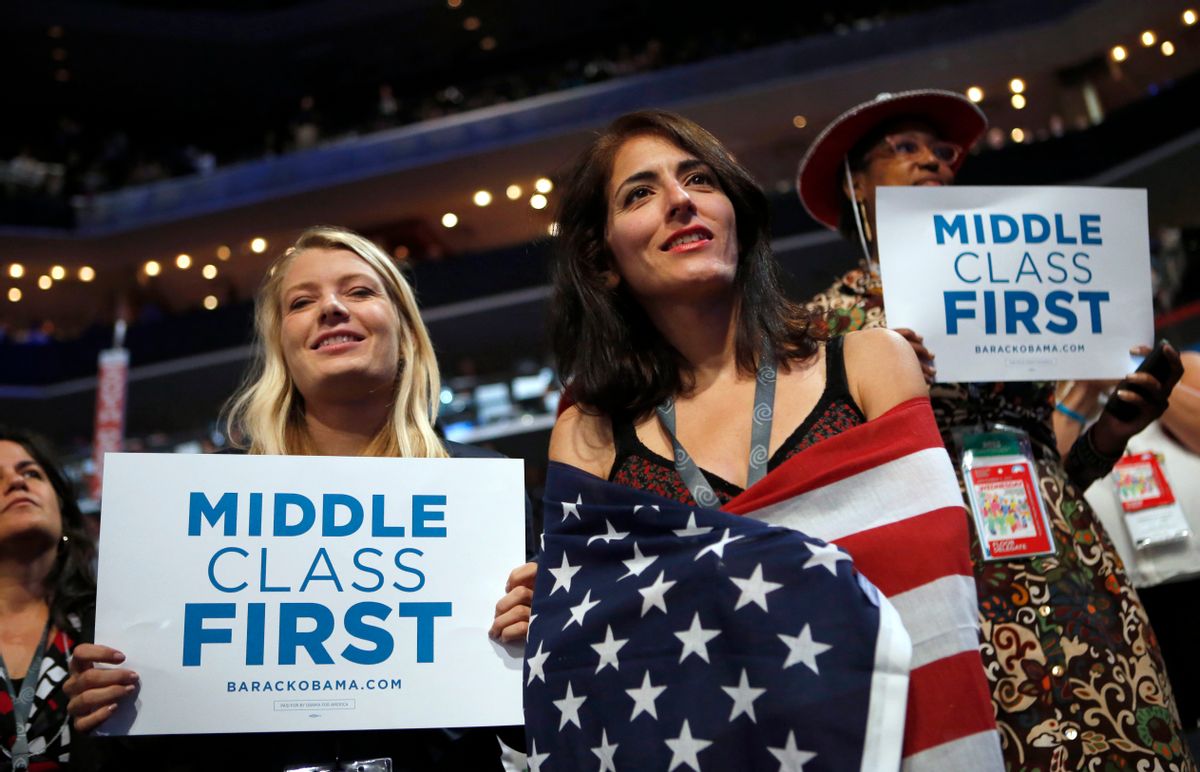

“If the president wants to use populism to sell his tax plan, he ought to consider actually putting his money where his mouth is and putting forward a plan that puts the middle class, not the top 1 percent, first,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer said.

Trump’s plan mostly would benefit the biggest corporations and the wealthiest individuals. But Schumer’s Occupy-Wall-Street-like whack at the top 1 percent and defense of the so-called middle class is muddled in a different way. That’s because it isn't the super rich, but the upper middle class — representing the top 20 percent, or households making at least $117,000 a year — that disproportionately have been doing better than the rest of Americans, the bottom 80 percent. Their tax breaks are one reason why.

“The upper middle class, the top fifth, broadly, and above, not only maintain their position very nicely, but perpetuate it over generations more effectively than in the United Kingdom,” said Richard Reeves, a Brookings Institution scholar and author of "Dream Hoarders: How The American Upper Middle Class is Leaving Everyone in the Dust, Why That is a Problem, and What to Do About It". “And yet, that that’s not so widely known or seen as a problem, because of the kind of myth of classlessness that has developed in the U.S.”

Comments like Schumer’s — defending a blurrily defined middle class — are a perfect example of the myth of classlessness that is parsed by Reeves, who was born in Britain but became a U.S. citizen. The biggest picture statistic he cites to frame the problem of improperly dissecting the economy’s real winners and losers is pre-tax income growth between 1979 and 2013. The bottom 80 percent saw their incomes grow by $3 trillion, while the top 20 percent saw their incomes grow by $4 trillion. When you put this on a graph, the bottom four quintiles, or 20 percent sections, slope upward slightly. But not so with the upper middle class; people making roughly $120,000 a year or more.

Why does this matter? It doesn’t just confirm what most Americans feel — that they are relatively stuck economically, perhaps doing better than their parents, but sometimes not even that. It shows that bashing the super-rich, the 1 percent, is politically expedient rhetoric that diverts the focus from those in America, members of both major parties, whose interests are maintained by the political system, instead of sharing the wealth. Reeves’ book, "Dream Hoarders", explains how the top 20 percent protects its status, essentially by segregating educational opportunity, their housing — which is federally subsidized through the tax deduction for home mortgage interest rates — career networking and other government-supported perks. As he recounts in a lecture that traces how he wrote his book, he started by noticing the politics surrounding a 2015 proposal by President Obama to change the way the feds managed tax-free college savings plans, called the 529 program.

“Don’t you dare touch my 529!” was the response upper-middle-class constituents told top Democrats, Reeves said, then laying out how these folks think: “Do you know how hard it is to make ends meet by the time I’ve saved for my kids' college, paid their private school fees, paid my massive mortgage — thanks for the [mortgage deduction] tax break; still it’s lots of money — I’ve got a skiing holiday, school trip gets more expensive, I’m barely making even here . . . I’m working really hard. I’m part of the 99 percent.”

“No, you’re not,” Reeves said, underscoring how the upper middle class is different. The 529 tax break was a college savings plan where you don’t pay any capital gains on money set aside and invested here, he explained. Who has these college savings plans? he asked. Forty-seven percent of people earning $150,000 or more annually, he answered.

“The truth was it [Obama’s proposal) was unbelievably unpopular among the constituency that really mattered … something that was virtually sacred for the upper middle class in America. It was about education. This was rewarding savings. It was about the future,” Reeves said. “For me, it was like, boom! No wonder we can’t change the tax system, when even relatively liberal people try to do it… People also forget this [529] was a tax break that has long been proposed by Republicans . . . Don’t mess with the American upper middle-class — that was the lesson.”

Reeves listed a series of metrics that he says amount to hoarding the American dream. It’s the inverse of the way social scientists talk about intergenerational poverty, or cite statistics about how most people don’t stray far from the rungs on the economic ladder of the family they were born into.

Thirty-seven percent of those born into the top 20 percent also stay there, he said, a slightly bigger number than the poorest 20 percent of Americans. “Wealth is even stickier than income. Forty-four percent of the wealth of the upper 20 percent remains there.”

Why is this happening? It comes down to hoarding the best opportunities in education, housing, careers and government tax policies that reinforce that status. This is not about inheritance taxes, which is a rarified subject. It’s how 40 percent of the upper middle class live near the public schools that have the best test scores. It’s how zoning in those communities only allows housing at price points well above those affordable by people earning median incomes — the real middle class. It’s about how the mortgage deduction allows people to buy even pricier homes. It’s about going to top schools, colleges and universities, and sending your kids there, and creating networks that turn into select entry-level jobs, internships and careers. In short, Reeves says all the political verbiage about equal opportunity, meritocracy and fighting inequality is sullied.

“Forty-six percent of those in the top 20 percent have the same educational status as their parents. The inheritance of educational status is even greater than wealth, which is even greater than income," he said. “The expansion of higher education in the U.S. has disproportionately gone to the top. Four out of five of those in the top 20 percent go to elite schools. Two-thirds of the students in the top schools are from the top 20 percent.”

On the subject of tax breaks — which will be coming to the national political landscape as Trump and the GOP push tax reform — the upper 20 percent gets the most capital gains benefits, mortgage interest deductions and Social Security and pension earnings, Reeves said.

“The point is clear. This is upside-down. These are upper-middle-class tax breaks,” he said. “And, like the 529, guided with laser precision to the bank balances of people like me: to the bank balances of people who have been doing so well in recent years. And by god, it’s hard to touch them. Even the incoming Treasury Secretary [Steve Mnuchin], he mentioned we might reduce tax rates but do so by getting rid of a lot of these deductions. Wow, that didn’t last very long. By the time the National Association of Housing and the Republicans [weighed in] . . . This stuff is hard to get at. I think part of the reason is we [the upper middle class] have kidded ourselves that we are part of the 99 percent.”

Reeves said that nine out of 10 Americans tell pollsters they are middle-class. That isn’t accurate or useful on many levels, he said, especially when it comes to addressing the lingering frustrations about one’s place and prospects in the American economy.

“I have genuinely come to believe that unless the conscience of the American upper middle class is somewhat awakened, then it will be very hard to bring about the political reforms that I believe are necessary . . . to one of equal opportunity,” he said. “Right now, America, some of America, has something of a problem of a sense of entitlement. And I mean the upper middle class. And they are very good about sometimes talking about people who feel entitled to welfare; I think they feel pretty entitled to their upper-middle-class welfare too. I think Obama found that out too.”

Indeed, Reeves said it is not very useful for Democrats to keep pushing out the rhetoric blasting the 1 percent, because among other things, that's not what’s really going on, and it doesn't address structural inequality.

“I think that until and unless we recognize that we are not the 99 percent, that we have done pretty well, and that we will have to give something up — not much, but a bit, a bit on zoning, a bit on school admissions, a bit on taxes, in order to help the others — then we won’t get anywhere,” he said. “But that will require us to recognize that we are not the losers from inequality trends, but the winners.”

Shares