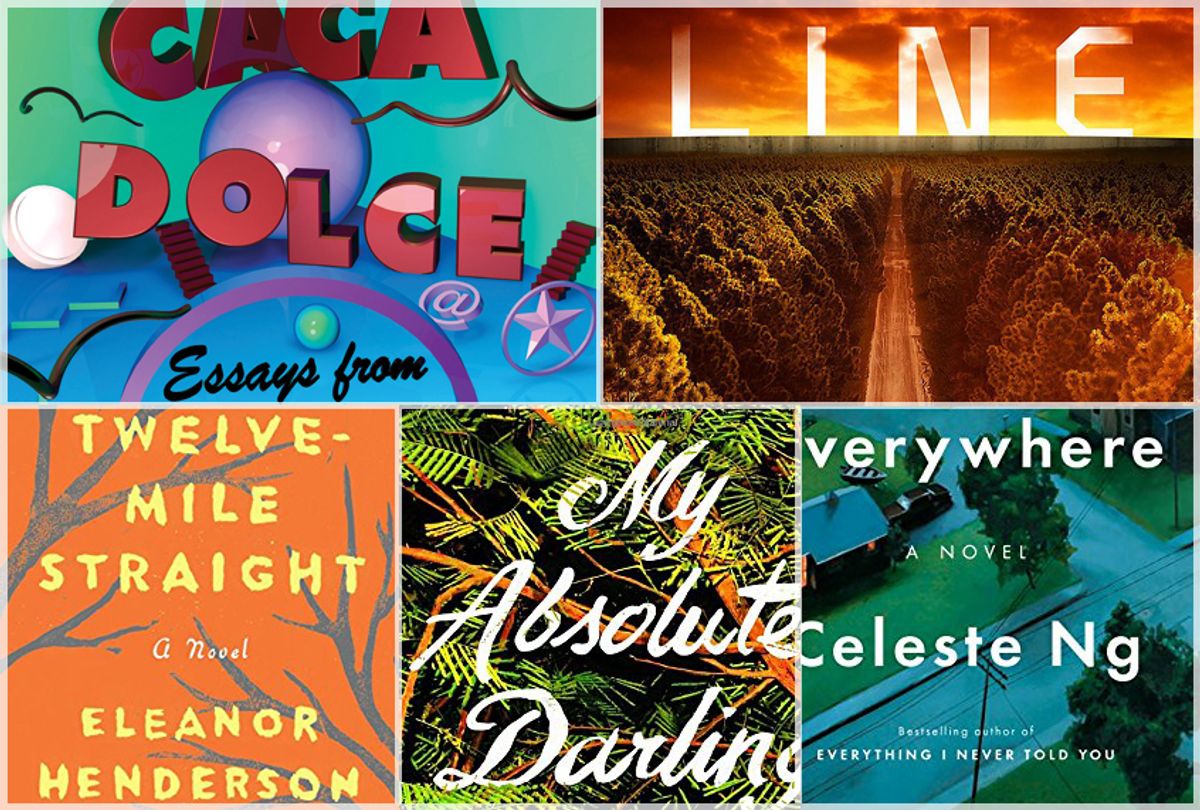

For September, I posed a series of questions—with, as always, a few verbal restrictions—to five authors with new books: Eleanor Henderson ("The Twelve-Mile Straight"), Holly Goddard Jones ("The Salt Line"), Chelsea Martin ("Caca Dolce"), Celeste Ng ("Little Fires Everywhere") and Gabriel Tallent ("My Absolute Darling").

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

Gabriel Tallent: The search for strategies of resistance when resistance seems impossible and also the life-changing magic of tidying up.

Celeste Ng: Mothers and daughters -- both biological and chosen. Where art and life intersect and how they speak to each other. What happens when good intentions run into personal discomfort. The dangers of thinking that plans and rules will save you, which is maybe the futility of believing you can really control anything. The (im)possibility of starting over.

Eleanor Henderson: Sharecroppers, bootleggers, midwives, a cotton mill, a lynching, poverty, paternity, family, community, the disease of Jim Crow, other diseases, white savior complex, twins.

Chelsea Martin: Specific tips and tricks for those who have allowed shitheads into their lives, facts and figures about being a shithead, lots of insight about shitheads. But also beauty, you know? The fleeting kind no one expects and then it’s gone and you forget what was ever beautiful. Also the more obvious kinds of beauty, which are also great. Plus, the age-old question: why? (re: family) and, on a related note, whhhyyyyyyyy?????

Holly Goddard Jones: Killer ticks.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

Jones: Mexican drug cartels. Chocolate chip pumpkin muffins. Perinatal depression. Accidentally sitting in a chigger nest. Donald Trump. Zika.

Martin: I wanted to get through this interview without mentioning bagels but here we are, I guess. Bagels. Sourdough. Art I made a long time ago that I know I didn’t throw away but that’s nowhere to be found. Conversations that have been stuck in my head for twenty years. The need to be heard without speaking. Rye, somewhat.

Tallent: Waiting with a dying seal hauled up on the black sand beach to die, sitting a ways off from him, keeping the vultures away, watching the rising of the tide in a cove soon to be flooded, reading the work of a tragedian killed by a falling tortoise who’d reportedly been staying out of doors on account of a prophesy that he’d be killed by a falling object.

Ng: A very small sampling of the many things that influenced the book in one way or another: Amy Heckerling; the Shakers; growing up in Cleveland in the 1990s; an adolescence spent in suburbia; the 1997 World Series; “Luv Me Luv Me” by Shaggy and Janet Jackson; Cindy Sherman; parenting.

Henderson: My father’s stories about his childhood on a Georgia farm during the Great Depression; the Great Recession; FDR; a documentary about fetal development; photos by John Vachon, Marion Post Wolcott, Jack Delano, Arthur Rothstein, and other WPA photograhers; Brian Brown’s blog Vanishing South Georgia; music by Blind Willie McTell, Woody Guthrie, Abner Jay, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe; a gourd tree at the Georgia Agricultural Museum.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

Henderson: Giving birth; Mom dying; nursing; teaching students; waking up at 5 AM to write while nursing; teaching students while nursing; reading drafts aloud to Baby while nursing; Baby stopping mid-nursing, smiling up at my voice.

Jones: Two pregnancies and new motherhood. Dying mother-in-law. Aging dog. Car wrecks. "Game of Thrones," "True Detective," "The Americans," "Broad City," and anything else I could binge-watch while bouncing a fussy baby.

Ng: Book tour; parenting a preschooler; gut-renovating a house while I was still living in it.

Martin: Left LA for Michigan, found some baby bats in the basement, took the bats to a bat sanctuary, ran out of money, made emojis, was eating a lot of pork products actually.

Tallent: Black coffee, campfire coals, sleeping bags filled with windblown sand; dutch oven enchiladas and cheap beer and the company of friends.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

Martin: I don’t believe I have experienced this particular feeling.

Jones: “You don’t write like most women.”

Tallent: Once you’ve written a book, its interpretation is out of your hands. That’s why you work like hell writing it. The other stuff, the stuff that is off base, you cannot help that and that is not very much about you.

Ng: Honestly, if anyone reads my work, they’re doing me a favor, so they get to use whatever words they want to describe it. I can’t control that, nor if they like the work, so best not to even try.

Henderson: I am mostly grateful for the words people use to describe my writing, except one I heard from an editor who rejected an essay she called “sweet.” Who the F you calling sweet?

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

Ng: A drummer. Or a sculptor.

Henderson: Farmer, bootlegger, midwife.

Martin: Restaurateur.

Jones: FBI profiler.

Tallent: Climate activist or a professional adventure sports photographer. Not a famous one, an unknown one who hangs out drinking beer with athletes who are too homely and too disorganized to ever make it big, but who love the hell out of the sport.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

Tallent: I’m a demon coffee drinker, but have lots yet to learn about whiskey and malt beverages, and know even less about typewriters and scarves and coffeehouses, all of which I’m given to understand are lynchpins.

Martin: Good with brevity, bad with giving quiet moments their space.

Jones: I think I have a knack for making backstory interesting, but the flipside is that I always write too much. I wish I had better instincts for what to leave out so that I wouldn’t have to make so many painful cuts when I revise.

Ng: I think I’m good at metaphors and descriptions. Plot doesn’t come naturally to me, so I work really hard at it.

Henderson: I think I’m good at transitions, which are underrated—the connective tissue, the getting from Point A to Point B. I would really like my next book to be funnier. This book has approximately one and a half jokes.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

Jones: I guess I don’t contend with it.

Henderson: I want to make another bootlegging joke but I’m not funny enough. The real answer is that I contend freshly with this every day, and that what helps is remembering that other people’s writing matters to me, and that what I’ve written before has mattered, reportedly, to others. Except that lady who called it “sweet.” F her.

Tallent: If you’re talking about the writing, I guess I just wanted to put true things on the page, in case there should ever be someone who might read them and feel less alone. I was never anxious that other people should find it interesting. You don’t write a book for everyone. You write the book for someone who might find solace in its pages, and yeah, it’s true, there is no certainty here, but even that doubtful chance seems worthwhile to me. And all the rest, you let go.

Ng: Well, you asked me for these responses, so . . . In all seriousness, I don’t ever assume people will want to hear what I have to say; I write because I’m trying to figure out what I think. For me, the process of writing is slowly articulating to myself something that’s important to me. If someone else also finds that thought meaningful, then it’s a bonus, but if others don’t find it interesting, that’s okay—not every book is for everyone.

Martin: Great literature is not for everyone.

Shares