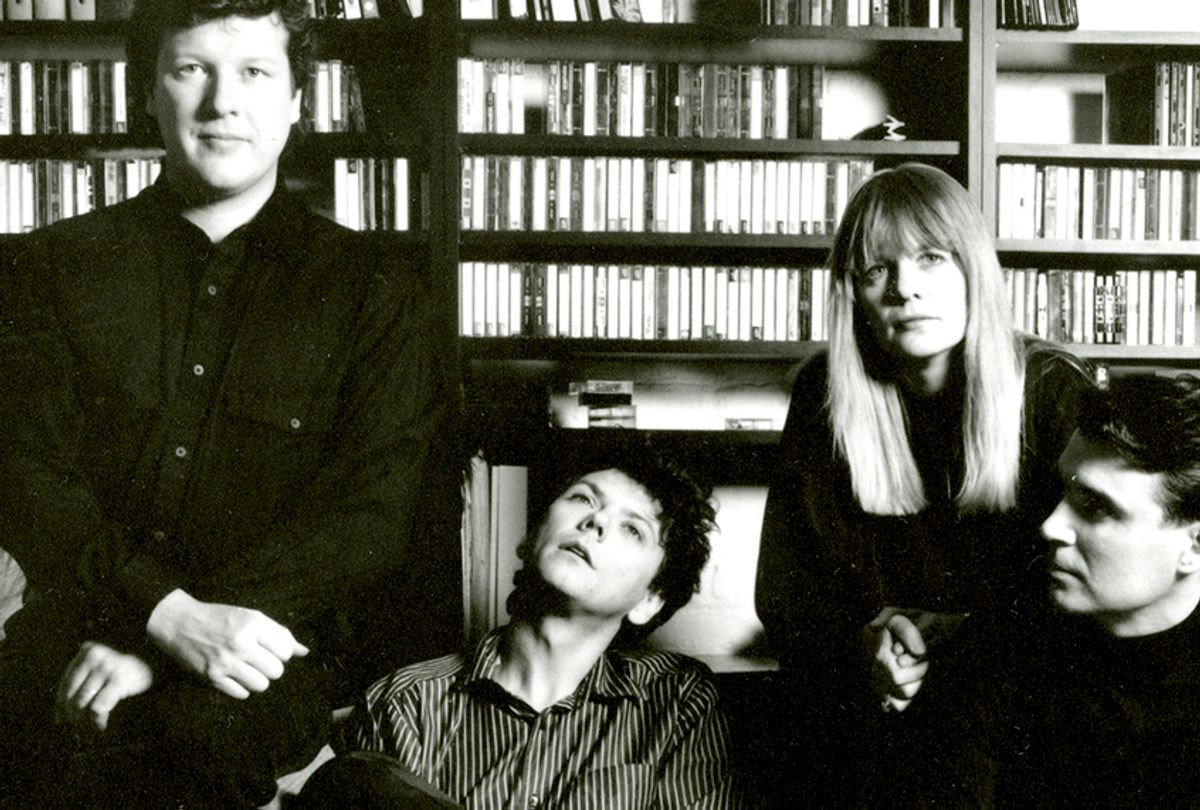

Last year, the rumor mill went into overdrive with whispers that Talking Heads might be reuniting. The very idea was momentous: Save for a 2002 appearance at their Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction, the beloved post-punk quartet — guitarist/vocalist David Byrne, bassist Tina Weymouth, drummer Chris Frantz and guitarist/keyboardist Jerry Harrison — hadn't done a proper gig as Talking Heads since 1984. (Byrne and Harrison joined Frantz and Weymouth at a Tom Tom Club gig to play "Psycho Killer" in 1989, however.)

The rumored reunion never materialized, of course — the source was a dubious satirical news site, and Frantz further told BlastEcho, "I wish it were true. It should be happening but [frontman] David [Byrne] is holding out" — but the fervor illuminated the enduring affection toward Talking Heads. Formed in 1975 in New York City, the band combined surrealism and whimsy in smart, inventive ways that were aligned with a multi-cultural rhythmic backbone, forward-thinking genre hybridizations and an askew approach to sounds.

This legacy began with the band's debut LP, "Talking Heads: 77," which was released on September 16, 1977. The words "minimal" or "minimalist" were often used at the time to describe Talking Heads, which is entirely correct. The record's music is spacious, almost self-indulgently so, and deliberate. Every sound — a frayed guitar riff, a lurking bass line, confetti-shower piano, a rattlesnake drum roll — has a purpose and place and works in meticulous tandem with its surroundings. Even the cover's stark nature is streamlined: It's a brilliant tomato-red color with green text spelling out the album's name in a classic typeface that recalls a storied newspaper.

Because things are so orderly, "Talking Heads: 77" possesses an aura of simplicity. On the watercolor soul-funk jam "The Book I Read" and the deceptively carefree "Don't Worry About the Government," this austerity is soothing. During other moments — the self-explanatory "Psycho Killer," the haywire twirl "New Feeling" — Talking Heads' methodical approach drums up tension. The push-pull between these moods gives "Talking Heads: 77" a balanced sound that speaks to the band's instinctual bent; the album is never too rigid or laissez-faire.

"None of us read music," Weymouth told Vivien Goldman in the June 26, 1977 issue of Sounds. "We all suspect technique, because so much of that early '70s technical prowess just turned out boring. I have a basic idea about what a rhythm section, bass and drums, should do. I dislike flashiness, I think it's ridiculous. If people clap because it sounds good, that's the point.

"It doesn't matter that they don't realize you're playing something complicated which sounds simple," she adds. "I'd sooner play something which sounds simple and repetitive than clutter up the sound. It's all a case of keeping the beat and carrying momentum."

Indeed, "Talking Heads: 77" has its own singular internal rhythms and structures governing the music. Calling the record post-punk or new wave makes sense, because it's a pastiche of granular influences (e.g., soul, dub, tropicalia, folk, '60s rock) stitched together in precise and different ways. Harrison's keyboards cushion the main melodies and instrumentation, buoying the music without taking up too much space, while hints of exotic percussion or unorthodox instrumentation add subtle accent colors.

Such an economical approach also permeates the lyrics, which resemble running narrations from omniscient protagonists. "Uh-Oh, Love Comes Town" describes in matter-of-fact terms what happens as someone falls into a romance; "New Feelings" reads like a detailed monologue dissecting nostalgia and the progression of time; "Happy Day" is a charmingly child-like recounting of a special memory. The most effective song is "No Compassion" — a timeless tune about having zero patience for people who wallow in problems rather than solving them — which ends several verses with the brusque statement, "They say compassion is a virtue, but I don't have the time."

Yet "Talking Heads: 77" is also full of subtle complexities: "Tentative Decisions" is a mirror image of sorts, with lyrics that flip genders halfway through in order to illustrate a relationship's shared anxieties, while "Don't Worry About the Government" scans like naïve, misplaced trust in leaders ("I see the laws made in Washington, D.C./I think of the ones I consider my favorites") and illusory comforts.

The concerns detailed on "Talking Heads: 77" feel universal, perhaps because Byrne uses a detached, observational tone and shares concerns without being preachy. Still, the record's dispassionate edge is mitigated by his rubbery delivery: Byrne uses wordless noises for effect on the tropical "First Week/Last Week . . . Carefree," and employs clenched-teeth wails, animated vibrato and theatrical exhortations. It's catharsis that's indicative of the band members' insistence on resonance.

"One of the reasons why we decided to take the risk and make the band, even though we weren’t sure at all how we would be received and we knew it would be a lot of work, was because we were very disgusted with the art world," Weymouth told Big Star magazine in 1977.

There was so much heroizing, and the artists that we met were so inflated with themselves — not all of them, but a number of them — and so full of themselves. People really looked up to them as though they were magicians, real heroes, and they thought of themselves as elitists: fine artists, and therefore very noble, and I think that kind of turned us off.

It really made us decide we don’t like heroes; we don’t like any of that, and we’re certainly not going to be heroes ourselves. We’re not gonna do that; we’re always gonna be normal people. We’re not gonna be pretentious and try to have people look up to us as though we’re something special. We try to stick to that pretty much.

Despite such self-effacement, Talking Heads were special. Critics, to their credit, tried to dig into Talking Heads' nuances and how the band fit into the burgeoning New York scene. For example, the Rolling Stone review of the album wrote, "Dressing like a quartet of Young Republicans, playing courteously toned-down music and singing lyrics lauding civil servants, parents and college, Talking Heads are not even remotely punks. Rather, they are the great Ivy League hope of pop music."

The band members themselves also resisted being lumped in with the punk movement, as they recognized such a monolithic tag didn't make sense. "We don't feel that in our performance we typify that angry attitude," Byrne told Melody Maker's Caroline Coon in the May 21, 1977 issue. "We don't eschew the primitivism — you know, the less is more and the more is less — but that's not quite what we're doing.

"They tend to believe that if you do something in a slick way, then it has no feeling. We don't hold that to be true. That doesn't necessarily mean we want to be real slick. At the same time, just not being slick doesn't mean that it's coming from the heart.

"I like to leave it up to someone else to say whether we're New and that's Old," he adds. "I didn't think of the band as joining the new wave but I did start out by thinking that I'd like to do something a little fresher than what you see in the chart!"

"Talking Heads: 77" did sound fresh, and it didn't take long for people to catch on. Although the album stalled at No. 97 on the U.S. album charts and "Psycho Killer" reached No. 92 on the singles charts, the band's next record, 1978's "More Songs About Buildings and Food," peaked at No. 29 on the pop charts and spawned a Top 40 hit with a cover of Al Green's "Take Me to the River." Talking Heads added depth, texture and shading on future records, but the sturdy foundation the band built with "Talking Heads: 77" lingered for the rest of their career.

Shares