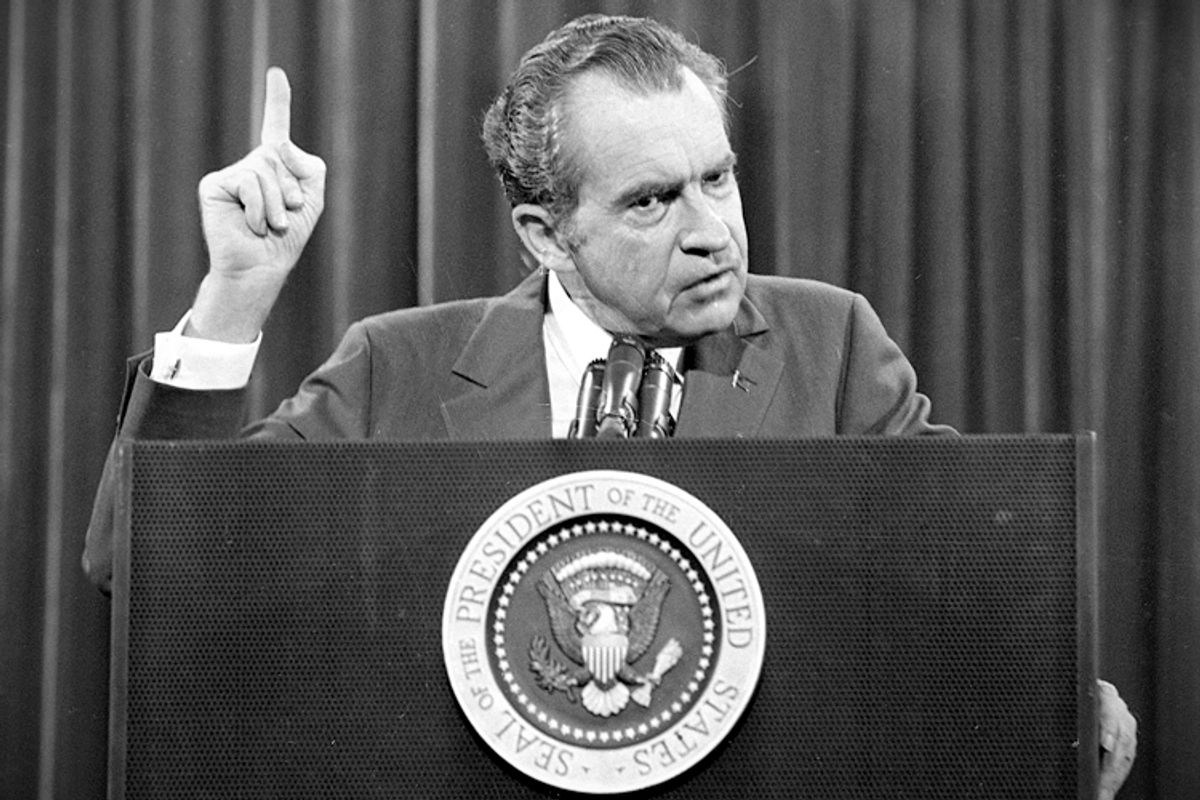

“This country is going so far to the right you’re not going to recognize it.” Those memorable words were uttered by Richard Nixon’s Attorney General, John Mitchell, who proved to be off by almost 50 years. But he and other Nixon cronies, however premature in their timetables, were establishing precedents for today’s worst case scenarios. We have to ask: Which elements of the state-sponsored violence of the ’60s and early ’70s are ready for revival and renewal? What new wrinkles in constitutional crisis might be in the works? Just how far to the right — or the left — will we go?

On taking office in 1969, Mitchell had declared that he was “first and foremost a law-enforcement officer.” The extent of the law-breaking — including murders — that that he and his cronies supervised against radicals, black militants and Democrats, is still coming to light. We have known for decades that the FBI informant drugged the Black Panther Chicago leader Fred Hampton, in December 1969, so that he was helpless to resist when two Chicago cops shot him in the head, in his bed, in the middle of the night. We know of a host of dirty tricks the Bureau deployed to deepen paranoia and internecine warfare in the Black Panther Party, in the New Left and the women’s movement.

Moreover, only recently has it been established, thanks to the research of the historian Arthur M. Eckstein, that in September 1970, high officials of the FBI proposed to Director J. Edgar Hoover that in case of “a state of national emergency” internment camps should be opened — or rather, reopened, for these were the same camps that between 1942 and 1946 held almost 120,000 Japanese-American citizens. This time, they would house 11,000 radicals — what the FBI called “the Security Index.” (I was one.) Habeas corpus would have been abolished. But the FBI was reluctant to commit. In an early appearance of Steve Bannon’s “administrative state” — the one he thinks must be “deconstructed” — many among the 9,000 FBI agents of 1970 preferred fighting crime to keeping tabs on domestic radicals who had committed no crimes.

As the FBI dragged its feet, they didn’t know — no one did — that the state of emergency was a hair’s-breadth from activation. On March 6, 1970, the Weather Underground readied three explosions to “bring the war home” — to America. One exploded prematurely in a townhouse on West 11th Street in New York’s Greenwich Village, killing three of the bombers themselves; the plan had been to detonate it at a dance at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Two other bombs were set to go off in Detroit — one inside a police station, the other outside a police social club. Both were exposed by an FBI informant. The second one was barely diffused in time. Had all three terror attacks gone off as planned, more than a hundred people would likely have been killed. In the full-blown panic that would have ensued, almost certainly President Nixon would have declared a state of emergency. Chance intervened. The emergency wasn’t declared.

It was also good luck that, two years later, a keen-eyed security guard in the Watergate Hotel discovered duct tape that prevented the locking of a door to the Democratic National Committee office. Police arrested five burglars, who were installing wiretaps. A dogged federal judge, John Sirica, himself a Republican appointee, established that these men were White House employees. The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein established that they were being paid through a Republican slush fund. Good luck doesn’t prevail if institutions don’t work.

How the country was kept from “going so far to the right you’re not going to recognize it” during the Nixon years was partly a matter of luck and partly the triumph of three institutions: the courts, the press and Congress, which launched the proceedings that resulted in President Nixon’s resignation. Nixon, like Trump today, confronted a resistance, and that resistance moved Congress to stand up for the Constitution.

Four years later, Mitchell was convicted of conspiracy, including the inept break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate Hotel in 1972, obstruction of justice and perjury, for which he served 19 months in prison.

How do we stack up today? Two of the three protective institutions of this battered democracy are standing up to obstruct the depredations of the Trump regime: the courts and the press — the part that Trump calls “the enemy of the people.” Whether Congress will hold its own remains to be seen. The midterm elections next year are up for grabs; signs point in both directions. But America’s narrow escape was not a foregone conclusion during the Nixon years. Nor is it today.

For all the auspicious signs, it’s by no means clear that today’s resistance will successfully withstand the tyrannical forces that are preparing to round up hundreds of thousands, or millions, of immigrants — the forces that offer free Army surplus tanks and bayonets to local police departments; that encourage and placate and pander to white supremacists, some of whom march with semiautomatic rifles and lit torches, and others of whom include an Arizona sheriff found guilty, by a federal judge, of criminal contempt of court for terrorizing brown-skinned people and interning them for months on end in what he unabashedly called “a concentration camp.”

Will the energies of resistance convert to political power? Unknown. The present Congress, for all its collaborations with Trump, has thwarted some of the Republicans’ incipient stampedes. Still, he has already done great damage through executive orders, through appointments hostile to public missions and the allocation of political commissars to run the executive branch. What will happen when lower-court decisions arrive at the Supreme Court for final disposition is by no means clear.

During the Nixon years, violence and intimidation against the resistance were rather coordinated. The printers that published underground papers were intimidated to stop by the FBI. The conspiracy trials of activists were centrally mobilized. Today, there are many more wild cards. The white supremacists are organized, and getting more so. (Not that vigilantes were unknown in the ‘60s. Murders of civil rights activists by Klansmen and other white supremacists were legion. Offices of underground papers were shot into and burglarized. In 1969, the early SDS leader Dick Flacks, a visible anti-war activist, was savagely assaulted and almost killed in his office at the University of Chicago. The assailant was never found.)

Here’s an indisputable fact from the past that should not be forgotten: As the Vietnam war became less popular, so did the increasingly confrontational anti-war movement. The residue of the New Left trailed off into suicidal bravado. One thing that doesn’t change is that fringe activists who harbor revolutionary fantasies and shrug off their real-world impact frighten the unaffiliated and win cheers for “law and order,” even from citizens who disagree with the president’s policies. Demonstrations then were hijacked by flag-burners and arsonists. Today, they’re hijacked by window-smashers and go-for-broke black-bloc goons. Armed collisions between racist militias and antifa bullies are all too plausible. As we learned in Charlottesville, the police haven’t yet figured out how to dampen the lethal potential. Then and now, the slug-first-ask-questions-later thugs muddy the prospects for nonviolent change. They panic the bulk of the population. They promote the version of “law and order” that comes from the mailed fist.

Add that it’s by no means clear that the commander-in-chief of the White House has the slightest respect for constitutional processes. The sum of his grandiosity and recklessness, and the grandiosity and recklessness of his violent opponents, is the reason why, today, all bets are off.

Shares