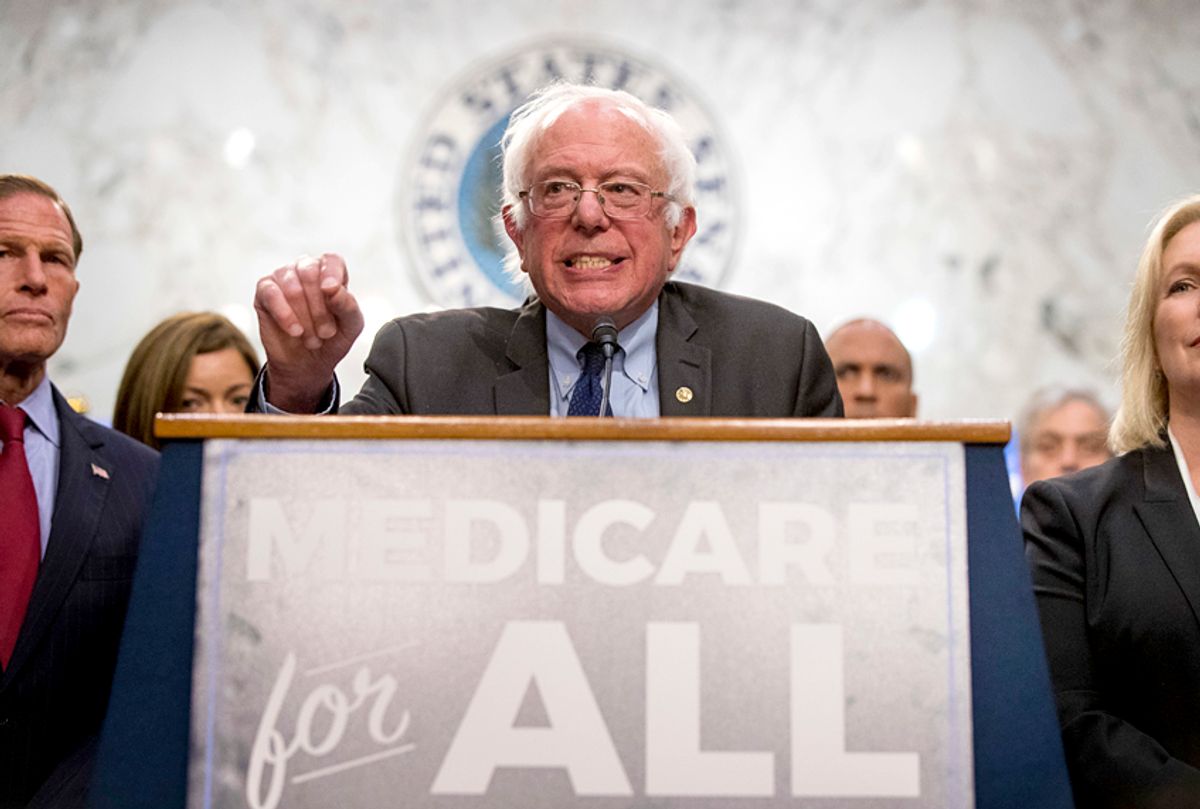

“Medicare for All” is an idea whose time has finally come — at least conceptually, which is more than half the battle. When Sen. Bernie Sanders announced his "Medicare for All" plan last week, he had 16 Senate co-sponsors, compared to exactly none when he proposed a similar bill in 2011. That's a third of the Senate Democrats, and more importantly, it included several perceived contenders for the 2020 nomination, such as Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Kamala Harris of California, Kirsten Gillibrand of New York and Cory Booker of New Jersey.

What's more, there's now a 53 percent majority supporting the idea, according to a June Kaiser Family Foundation poll, with independent support at 55 percent, up 12 points since 2008-9. Support was malleable in both directions. Arguments against — raising taxes and giving government too much control — could raise opposition up to 62 percent, while arguments in favor — reducing administrative costs and ensuring health care as a right — could raise support to 72 percent. Support among Democrats, at 64 percent, should naturally be expected to rise if the leading primary candidates all support the idea.

Yet there was immediate pushback, and not just from Republicans, as might be expected. The story headlines alone tell the tale of peril — "How Single-Payer Health Care Could Trip Up Democrats," by Margot Sanger-Katz at the New York Times, “'Medicare for All' will be a trap for Democrats if they're not careful,” by Josh Barro at Business Insider — or folly — “The Single-Payer Insanity,” by Bill Scher at Politico, “Bernie Sanders’s Bill Gets America Zero Percent Closer to Single Payer,” by Jonathan Chait at New York magazine. These knee-jerk responses are all in the name of realism, of course, but it's more like the "crackpot realism" derided decades ago by C. Wright Mills. The reality it refers to is falling apart all around them, as the underlying assumptions have simply ceased to hold.

What's now emerging is a clearer-than-ever divide between those still buying into existing politics — even those with undeniable progressive instincts and values — and those who want and demand fundamental change. While it's still very important to heed "reality-based" arguments, from a larger historical perspective, these arguments themselves lost touch with how rapidly and reality is changing. If the old common-sense assumptions had held, Bernie Sanders would never have won single a primary and Donald Trump certainly wouldn't be president today.

Not just here in America but across Europe as well, the existing political consensus is eroding. Something new is almost surely going to replace it — the only question is what. It won't mean throwing everything out, wholesale. But it will mean reassessing things in a whole new light. The common sense of what “everybody knows” is changing and everybody knows that, even those who are still clinging desperately to their denial.

At the New Republic, Clio Chang's lucid rebuttal, “Why Bernie Sanders’s Medicare for All Plan Is Good Politics,” highlights some of the key false assumptions made by critics. To begin with, she quotes Sanger-Katz:

Like “repeal and replace,” “single-payer” is a broadly popular slogan that papers over intraparty disagreements and wrenching policy choices. ... If the Democrats eventually wrested back power, they could find themselves similarly factionalized and stymied over the details.

And Chait:

At no point does [Sanders] grant that the most important source of opposition will come from actual American voters concerned about losing their current plan or paying higher taxes.

Then Chang observes:

What these criticisms share is an underlying belief that Democrats are racing leftward on health care for short-term political gain — namely, appeasing the demands of the progressive base — without taking into account the long-term repercussions and whether Medicare for All is even feasible. But Sanders’s proposal is not a cynical slogan like “repeal and replace,” nor is it an inflexible roadmap that will invariably lead to a political dead end. It is better understood as a historic breakthrough in the way that Democrats approach health care, opening the door for all kinds of fixes to a system that nearly everyone agrees is too expensive and too inefficient.

Chang's point ought to be so obvious it goes without saying. But clearly it's not. But fast forward two years to 2019, with the 2020 Democratic primary in full swing, and it almost certainly will be. “Repeal and replace” had no content to it — it was all sizzle, no steak. There was no “there” there. It was the hollowest of slogans, even apart from the cynicism involved. “Medicare for All,” in contrast, stakes out an aspiration of universal coverage already achieved by other advanced industrial nations. It overflows with possible alternatives, even as Sanders has thought carefully about how to craft the specific proposal he advanced this week.

As Chang goes on to note:

[A] party that is united in this goal, but divided on the means of attaining it, can still be an effective one. Amidst Sanders’s push for single-payer, we have seen alternatives being developed by other Democrats like Chris Murphy and Brian Schatz, both of whom are committed to the goal of universal coverage. Critics say Sanders’s plan precludes more incremental approaches, but you can also say that the momentum Sanders is building helps generate more of them.

At Think Progress, Ian Millhiser posed “7 tough questions single-payer advocates must answer before their ideas can become law,” which can function as a sort of Rorschach test. It can be read in naysaying fashion, as a corollary to the knee-jerk criticisms Chang was responding to — especially when referencing an early August article in the Nation, “Medicare-for-All Isn’t the Solution for Universal Health Care,” by Joshua Holland. But it can also be read positively, as a serious to-do list for those working to make Medicare for All a reality, in one form or another.

Indeed, even Holland's piece is more complicated than its title suggests, as shown by how he draws on arguments from economist Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, who is a himself a single-payer advocate. Baker points out that the enormous cost savings other countries enjoy are the cumulative products of decades of cost controls. They can't simply be realized with the wave of a magic wand.

This is a crucial point that has to be addressed down the line. But it should not distract us from the fact that such savings are clearly possible. Gradual changes in cost structures that turn drastic over time are routine stuff in the world of budget wonkery. What's not routine is making them work for ordinary Americans, rather than against them.

Sher's piece at Politico adds something different, however. He argues:

The Democratic Party now is, for all intents and purposes, the party of single-payer health insurance.

Big mistake.

Democrats are committing themselves to years more of a treacherous health care debate, at a time when there are more pressing issues to confront.

There are two things wrong with Scher's argument here: First, it's ludicrous to think that health care would disappear as an issue if not for single-payer advocacy.

Sanders has a much more realistic sense of what's going on when he points out that the GOP attack on health care is going to continue, regardless of what Democrats do. The GOP attempt to destroy Obamacare was not just about tax cuts for the rich, as he told the Nation's John Nichols in a recent interview, it was about the whole Koch brothers’ ideology of dismantling government:

This is the beginning. If they are successful in destroying Medicaid, Medicare certainly will be next and Social Security not far behind that — and the Veterans Administration, as well. So this is part of a massive effort by the Koch brothers and other billionaires to take us back to the 1920s and to do away with virtually every major piece of legislation passed since the 1930s to meet the needs of our people.

An effort that grand in scope and sweeping in vision requires something equally grand and sweeping in opposition — and 50 years of history shows how desperately such a grand opposition is needed. This is the second problem with Scher's argument: It ignores the potential catalytic role that Medicare for All can play in helping to provide progressives and Democrats with much-needed coherence and sense of shared vision.

In their landmark 1967 book, "The Political Beliefs of Americans: A Study of Public Opinion," Lloyd Free and Hadley Cantril showed that Americans overwhelmingly favor specific liberal social programs for the results they produce — by roughly two-to-one — while more narrowly favoring small government and the free market in the abstract, as a matter of ideology. This “schizoid condition” is troubling when it comes to making public policy. In the book's closing section, “The Need for a Restatement of American Ideology,” they said, “There is little doubt that the time has come for a restatement of American ideology to bring it in line with what the great majority of people want and approve.”

Of course, that never happened, which is a big part of the problem confronting progressives and Democrats to this very day. The fight for Medicare for All could help change that, precisely because it has an ideological dimension — the belief that government has a vital constructive role to play in helping to make people's lives better — and because health care is so intimately important to virtually everyone in American society.

More recently, the book "Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats" by Matt Grossmann and David A. Hopkins (Salon review here), showed how the attitudinal divide discovered by Free and Cantril is reflected and amplified by different aspects of party political culture. The GOP has flourished as the agent of a coherent movement-conservative philosophy, while the Democratic Party has represented a pragmatic coalition of group interests advancing specific problem-solving policies. Each party would clearly benefit from being more like the other. If GOP policies actually produced promised real-world results, their governance record would improve significantly. And Democrats would surely win more elections if they better expressed what they stood for more broadly, as Free and Cantril argued 50 years ago.

That's where Medicare for All comes in. It engages virtually all the interest groups represented by the Democrats, so it's grounded in the party-as-it-is, even as it embodies an ideological perspective with the potential to unite them. The exact form that ideology takes is not predetermined: There are any number of ways that government can help make people's lives better, and a vigorous effort to come up with the best possible solution will only help make this abstract possibility increasingly concrete for tens of millions of Americans in the next few years.

Another reason why Medicare for All can be so crucial is its mobilizing potential. As Chang notes:

Setting up Medicare for All as a goal is a way to activate movement politics, to give people a reason to go to the polls and make phone calls. We have already seen the fruits of those efforts: that 16 senators have signed on to the plan is due more to sustained grassroots organizing than anything else.

Maintaining turnout — especially in down-ballot and midterm elections — has been a key Democratic weakness for the past 25 years, most notably in the disastrous 1994 and 2010 elections. The 1999 book "Reading Mixed Signals: Ambivalence in American Public Opinion about Government," by Albert H. Cantril and Susan Davis Cantril, found that critics of government made up 45 percent of likely voters, the same number as supporters. But among non-voters, supporters outnumbered critics by 55 to 32 percent. It could not be more clear: Consistently motivating voters who support government action is absolutely crucial for the future of progressive politics.

I should be clear: I am not arguing that nothing else matters. Scher asks, “[W]hy should Democrats prioritize junking what was just successfully defended, at enormous political risk, when there are so many other moral imperatives that warrant a robust and urgent policy response?” He mentions climate change, immigration reform, rebuilding infrastructure, etc.

He's not wrong. These and other issues are also vitally important. But Democrats aren't likely to make headway on any of them nationally, without winning back power at least in the House in 2018 — with a few rare exceptions, such as the chance to turn DACA repeal into passage of the DREAM Act. What's more, they are all connected ideologically by the belief that government is a vital part of the solution. So making that belief more salient, via Medicare for All advocacy — will help to advance them all.

Democrats can and do walk and chew gum at the same time. They've been doing it for decades. It's what their political culture is all about, as Grossman and Hopkins show in detail. What they haven't been doing is clearly communicating about what they are doing in a way that reaches and mobilizes voters when it really counts. They lack a clear, coherent message that resonates across issue areas, and into people's everyday lives. Medicare for All is not a unitary, quick-fix answer to that problem and no one should pretend it is. But it represents a clear path forward toward developing that message and nurturing the emergence of a new common sense. We'd be foolish not to take that path forward.

Shares