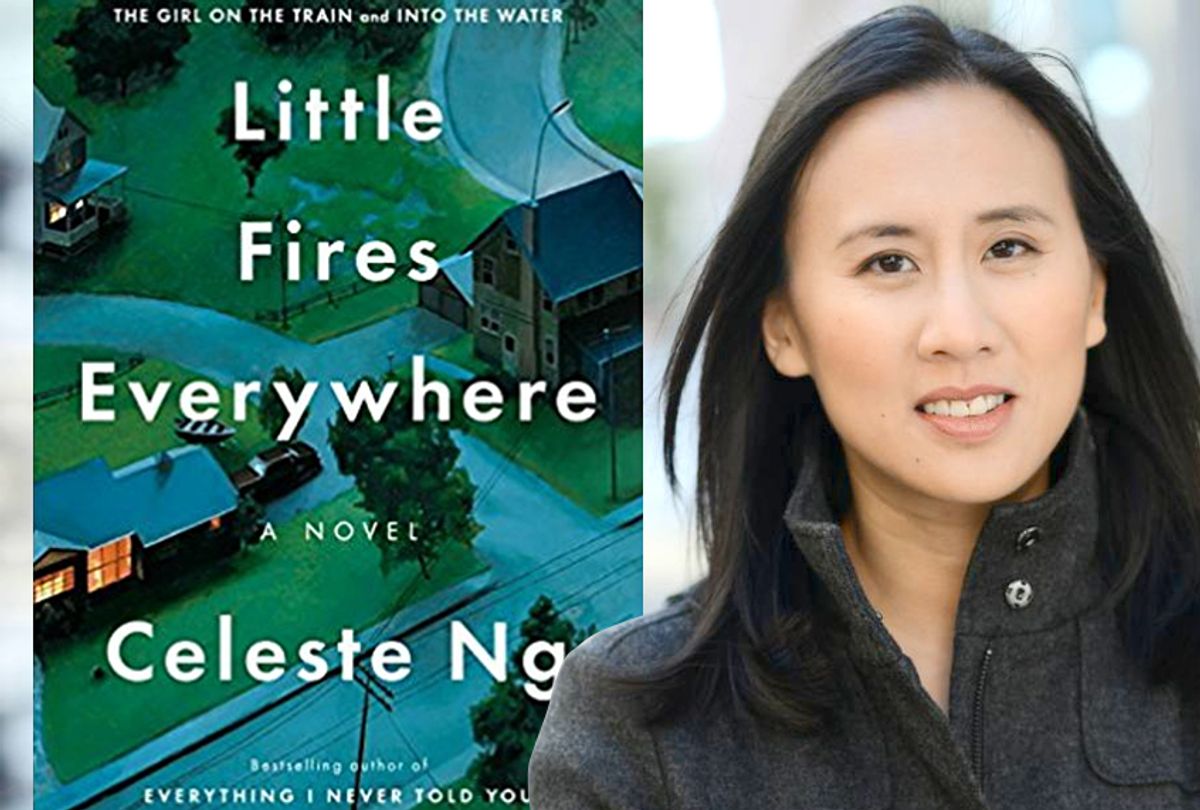

At a time when any book not involving dystopian futures struggles for public attention, author Celeste Ng has managed to release the most buzzed about novel of the fall, with a family drama set at the height of the Clinton era.

It's not that Ng's second novel, "Little Fires Everywhere," doesn't feel supremely timely. Set in Ng's own childhood turf of Shaker Heights, Ohio, "Little Fires" tells the tale of Elena Richardson and her seemingly perfect family, her free spirited tenant Mia and teen daughter Pearl, and a controversial custody battle that divides the community. As the characters careen toward cataclysmic events, they're swept up in debates about race, class and what it means to be a mother.

On the heels of praise from the likes of John Green and Reese Witherspoon, Salon spoke by phone to Ng during a break in her national book tour.

I’m going to admit I was embarrassingly far into the book before I realized that it does not take place in the present tense — like, “Wait a minute, they’re talking about Jerry Springer and they’re faxing things, and no one is looking at their phone."

No one has their phone, that’s right, and they don’t go to the internet. They just call directory services to try and find out somebody’s address.

What made you want to set it in this different time period?

The first reason was that that was the era in which I lived in Shaker Heights. I grew up there in the ‘90s. I would have been [the same] age as Lexie, who is the oldest daughter in the Richardson family. That was an era that I knew that I could flash back to really well. I knew what you could have done, what you wouldn’t be available to do. I had all these details ready, and that was the Shaker Heights that I felt like I was portraying. I don’t live there now; I remember what I experienced when I was there.

The second reason is that I knew I was writing about characters who had a lot of secrets and who were trying to keep them from each other. I feel like that can be done now, but it’s really difficult. You have to work really hard to not have an internet presence. You have to work really hard to not be so interconnected with other people that you could just move away and never be heard from again.

I needed to set a book in a time period where the characters had that space to preserve some of their mystery and where people would have to work hard to find out somebody else’s past and somebody else’s secrets.

It seems also that this was a period where these issues around what it means to be someone’s mother and who really is a mother were at the forefront of legal battles.

The '90s was an era in which those things were really coming to the front of the conversation. There was the Baby Jessica adoption case that happened in the early '90s, where a mother had given up her baby to a couple and then wanted her back. The sympathy at that time was almost entirely with the adoptive parents, and the child was eventually returned to the birth parents.

The '90s was also a period when China opened up its orphanages to overseas adoptions. I feel like that was the first time that a lot of people were having to think about these things. That hadn’t really happened before. Surrogacy was only really starting to be a real possibility at that time. We were starting to think really hard about, who is a mother? What does it mean to be a mother? All that was starting to be the conversation.

One of the things I also really love about the book is that there are very few real villains in it.

I didn’t want there to be a villain. I didn’t want there to be a hero either. I didn’t want anybody to come out looking shiny.

My goal is that the reader would at least see how they got there, even if they didn’t agree to all they were doing. I have a school-age son, so we talk about the whole "good guys versus bad guys" concept. One of the things that we’ve been talking about is that bad guys don’t really think that they are bad guys; they usually think that they are the good guys. They think that they are trying to do the right thing. And I think that’s true of most of the people in the book. They really are trying to do the right thing; it’s just that they can’t see, because of their blind spots, how their actions are affecting other people.

Even the least sympathetic character in the book, you can see why she does the things she does and what her process is, and also what her damage is.

There’s a difference between humanizing someone, recognizing what they do, and excusing them. And I think in a lot of ways, understanding how people get to those extremes would hopefully allow us to prevent that from happening again.

I think about this, because I live in Boston, about the marathon bombing. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev went to the public high school in Cambridge that is across the street from the coffee shop where I work a lot and next to the library, where I also work a lot. There was a backlash against the few teachers who said, "You know he was such a sweet kid in class, I remember really liking him." They were still trying to work through reconciling what he did. And a lot of people said, “No, he’s a monster!”

The thing is, if you say somebody is a monster, it’s not only bad because they lose their humanity, it’s also bad because you have no way to try and prevent other people from becoming “monsters,” right? He felt ostracized. He felt out of place. His brother felt out of place. Not to excuse it, but maybe that means that we need to try and make sure that people who are outsiders feel welcome in their communities, that they don’t want to take revenge. But I think we’re in an era when it’s becoming really hard, and I guess a lot of my work ends up being an argument for nuance and contradictory feelings.

You also bring out later in the book that it’s also important to understand that people who seem good in certain ways can do bad things.

That's how it works, right? People have really good intentions, and it doesn’t prevent them from making bad decisions, knowing that. And it doesn’t prevent them from having blind spots.

One of the things I realized I was writing about in the book was the way that we often have really good intentions, and we have these principles, and we believe that we live by them — up until the moment when it makes us personally uncomfortable. A lot of times those principles go out the window. I’m really interested in that breaking point, because I feel like that’s the point at which people are deciding which road they’re going to go down, and it’s something that you need to think about.

Do you feel that the book is spurring a lot of debate and conversation? I can so easily picture book clubs talking about, "Well, what side would you have taken in this story?"

Yes. I hope that it will. I hope that it does spark those kinds of debates, because frankly, I think we need that now. . . . I feel like it’s really important to have those conversations, because otherwise it becomes a topic that we’re really scared to touch.

This is part of the problem with “I don’t see race,” which is what I really remember from when I was living in Shaker Heights. That was really how we — myself included — kind of thought about race. I think now we realize how not effective, but also, kind of, how harmful that is. Because it suggests that we should just ignore all of these experiences and all of the context in history that you really can’t.

On social media you talk so much about politics, and you talk about little things that we can do. Do you feel like we can use social media in a way that it isn’t just a total garbage fire?

I hope so. Maybe I am overly optimistic, I don’t know. I started talking about politics largely because I felt like I have that responsibility. I don’t know how I got all these Twitter followers, but since they are here, I feel like it is important for me to talk about something that is important.

I was very much raised in that attitude that you should be a service to your community, service to the world, that we are here to try and like make things better. If people are listening, then I want to talk about those things.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Shares