In the spring of 2008, the strange story of a Georgia widow was tearing up the AP wire. In 1995, her 33-year-old husband, Terry, had committed suicide, ending his life with a single shotgun blast. His heart was salvaged and donated to a man at risk for congestive heart failure, 57-year-old Sonny Graham. Grateful for his new lease on life, Sonny tracked down the widow to thank her. When he met her, he felt like he had known her for years. Exactly like the previous owner of the heart beating in his chest, he fell in love with her. They got married. Eventually, he too killed himself with a self-inflicted gunshot to the head.

Scientists say they’ve documented more than 70 cases of organ transplant recipients who adopt the personality traits of their donors. Parapsychologist Gary Schwartz told the New York Post that living cells have memory cells that store information that can be passed along when the organ is transplanted. The examples read like "Twilight Zone" episodes. A 68-year-old woman suddenly craves the favorite foods of her 18-year-old heart donor, a 56-year-old professor gets strange flashes of light in his dreams and learns that his donor was a cop who was shot in the face by a drug dealer. Does a sample on a record work in the same way? Can the essence of a hip-hop record be found in the motives, emotions and energies of the artists it samples? Is it likely that something an artist intended 20 years ago will re-emerge anew?

Hip-hop is folk music. Melodies, motifs, stories, cadences, slang and pulses are all handed down among generations and micro-generations, evolving so rapidly that it’s easy to lose track of exactly where anything actually began. Check the technique and see if you can follow it:

- In 1986 in New York, Kool Moe Dee told careless Casanovas to “Go See the Doctor.”

- In 1989, Dr. Dre manipulated Moe Dee’s record, giving his self-assured baritone a case of the hiccups, making him stutter out “ the-the-Doc, the-the-the-Doc” on “Mind Blowin’,” a single by Dre’s protégée The D.O.C.

- In 1993, to show respect to his West Coast paterfamilias, Snoop Dogg vocally emulated the Dre-tweaked stutter on his debut single, “Who Am I (What’s My Name),” rapping he’s “funky as the-the-the Doc.” As the centerpiece of a multiplatinum album, Snoop’s version of the line ended up being the most popular one of all.

- Snoop was surely the influence when the line went back to New York in 1999, when Jay-Z started “Jigga My N----” with a salute to his Roc-A-Fella record label: “Jay-Z, motherfucker, from the-the-the Roc.”

- Influenced by Jay-Z’s unknockable hustle, Atlanta rapper Young Jeezy flipped Jigga’s rock-hard version in 2005 on “Bottom of the Map” with “I do it for the

trappers with the-the-the rocks.”

It’s similar to the way folk musicians update the storyline of a popular murder ballad or put their unique pluck on a familiar set of chords. Sampling, however is a uniquely post-modern twist, turning folk heritage into a living being, something that transfers more than just DNA. Through sampling, hip-hop producers can literally borrow the song that influenced them, replay it, reuse it, rethink it, repeat it, recontextualize it. Some samples leave all the emotional weight and cultural signifiers of an existing piece of music intact — a colloidal particle that floats inside a piece of music yet maintains its inherent properties. All the associations that a listener may have with an existing piece of music are handed down to the new creation — whether it’s as complicated as a nostalgic memory over a beloved hook or as elemental as a head-nod to a funky groove you don’t specifically recognize.

Take the piano riff in Joe Cocker’s 1973 hit “Woman to Woman,” used in 2Pac and Dr. Dre’s 1995 smash “California Love.” Upon hearing “California Love,” an older listener might associate the riff with how much they did or didn’t enjoy the Joe Cocker original. A younger listener might think of it as a hip-hop hand-me-down, associating it with the Ultramagnetic MCs or EPMD songs that sampled the riff in the late ’80s. An even younger listener might not recognize it at all but simply understand that, since it clashes against a high-polished Dr. Dre production, it’s something “old” or “borrowed” or “funky,” imbued with an odor that’s mysterious but still evocative.

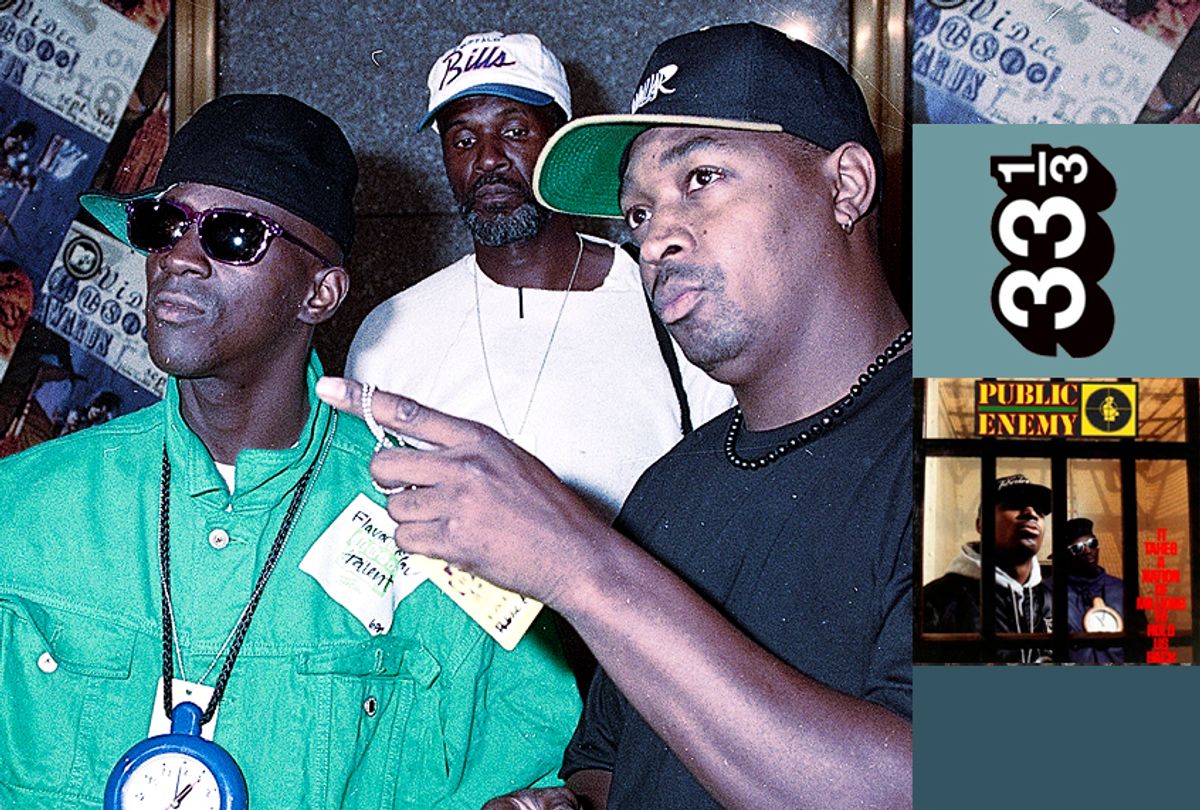

"It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back" is congested with 100 of these samples — maybe more — ranging from the familiar to the obscure to the completely unrecognizable. A guitar lick from British rock band Sweet adds to the delirious feel of “Cold Lampin with Flavor.” Is it enough to say that the track “Funk It Up” is a great circa-1976 groove chugger on par with Thin Lizzy’s “Johnny the Fox”? Or is it worth noting that, just like Public Enemy in 1987, Sweet in 1976 were trying to reposition their band as a heavier, meaner, steely-eyed alternative to their past work? Is it a coincidence that "Nation of Millions," an album focused on liberation, samples Isaac Hayes’ legendary move away from record company dictates, itself a singular success that followed a retail flop? Are the JB’s and Funkadelic and Temptations records that Public Enemy use permeated with special triumph and tumult since they originally appeared shortly after lineup changes?

“We use samples like an artist would use paint,” Hank Shocklee once said (George, Nelson. "Post-Soul Nation" New York City: Penguin, 2004). Their style was not the surrealist clouds of the Beastie Boys or the De La Soul sample collisions that would follow in "Nation of Millions’" wake. The Bomb Squad style of painting was a violent pointillism, taking a single guitar stab or drum kick and dotting the landscape until a song emerged. The Bomb Squad mistreated their samples — when one sounded too “clean,” Hank would throw the record to the floor, stomp on it and try again. They would occasionally break the (still standing) unspoken producer’s rule of “always sample the original recording” and sample a sample, just for an extra bit of chaos.

Their techniques were unlike anything of the era. And thanks to the diligent work of copyright attorneys, their cavalier, frontiersman attitude toward samples will never be repeated — at least not with the support and budget of a record label. They sampled dozens of records because there was never anyone saying they couldn’t. When Chuck envisioned the courtroom drama in “Caught, Can I Get a Witness,” a track in which he’s called in front of a judge because he “stole a beat,” it was a dystopic fantasy, a piece of fiction. Within a year, his story became reality.

Shares