The storm wasn't the worst of it for Alice Anderson and her children. After Hurricane Katrina hit Mississippi, her physician husband's already precarious mental health went into freefall. What followed was an ordeal that tested her physical, emotional and financial resources, and brought with it a lifetime's worth of lessons in what it takes to survive.

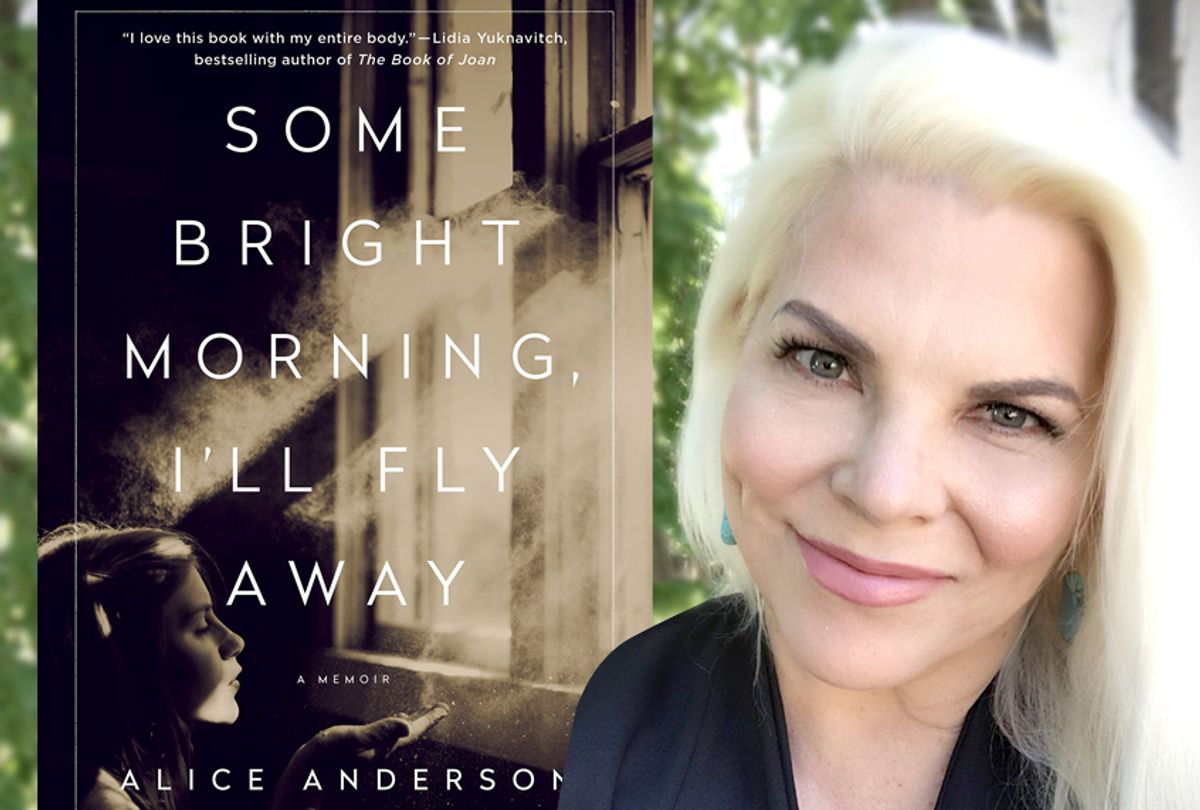

Now Anderson, a poet and former model, has released "Some Bright Morning, I'll Fly Away," her account of, as she puts it, building chapels out of the scars. Anderson spoke recently to Salon about rebuilding, both inside and out.

The book feels extremely topical in so many different ways right now. The book is really so much about the psychological aftermath of mass traumatic events.

In Mississippi, they always say, “The storm doesn’t change anyone. The storm reveals who you are.” When you see the coverage of a natural disaster of that size on the news and you read about it, there’s no way to really understand how it keeps impacting, how that storm keeps hitting both in large and small ways and how it continues to affect the family.

It feels like over the past decade that there’s been a different understanding of the impact of trauma.

It’s interesting to me because largely "Some Bright Morning" is about the storm and catastrophe, and then also the catastrophe of an abusive relationship.

Just like a storm, the catastrophe doesn’t end the day that the storm goes back out to sea. There is a very long tail. In fact, what happens after can be as or more dangerous as the original events.

What is it like for your children now?

Well, I’ve chronicled in the book, our living arrangements now are that we are a family of four. They lived for ten years going back and forth with shared custody, supervised visitation. It was like this terrible cycle.

But with the last final violent episode, now, we arrived at our "finally." Everybody lives without that specter of what’s going to happen next. We have a lifelong, renewable for life, protective order for all of us. He really isn’t in our life at all now. I didn’t want to write a book that was about just how we survived. The whole point of surviving was to get to this point, to this "finally."

Were you concerned, though, when you were writing it, about not just stirring up the presence of this person again in your life, but what did you have to do in terms of protecting yourself legally, physically? Were you thinking about those things?

I thought about them as I was writing. But I kept writing anyway. Of course, we changed names. We made sure that we were covered legally. At a certain point when I was writing this book, I stopped and it was because I realized I didn’t know how my story ended. Then one terrible July night, I’m driving in my car and I’ve got two of the kids in the car with me and we’re following the third in the ambulance. As terrible as the night was, I had the thought, "You’re driving through the end of the story."

As traumatic as it was, it was the beginning of the end of the story. I think once that played out and their father was convicted and we got a lifelong protective order, it gave me a sense of safety. But even so, people will ask me, “Are you worried about stirring him up? Are you worried that his makes it more dangerous?” But I fell back on, "Your silence will not protect you." It would be dangerous no matter what I did. That’s the reality when people ask, “Why did she stay?” The reality is the leaving is oftentimes the most dangerous thing.

The danger is there. But I just choose not to live in it.

What do you want people to understand from reading this book about the nature of abuse, particularly when it involves a family when there are children at stake?

I felt very desolate as I went through it. When the first incident happened and I was attacked with my children there, I had this naïve notion that this was obvious. I would go to family court. Of course, the family court would protect all of us. Then I descended into that system and realized, “That maybe that isn’t as simple as it seems.” But I didn’t want to write a book that had an ax to grind. I wanted to write a book that was about finding the beauty in the calamity.

The first line of the book is “We make chapels of our scars.” I was thinking about it the other day and I thought about a lot of times the scars, those wounds, whatever they are, physical, emotional within an abusive relationship, they become part of the dance. To me, when you've finally left and when you are finally free, those are yours and you make what you want of them. We can be stuck in where we were or we can reclaim the narrative and write the story.

It gets very, very complicated and very tangled, especially when you’re dealing with domestic and family violence, because also you have relationships with these people. You have had loved these people. It’s not like you’re walking on the street and a stranger punches you in the face.

Exactly. If my son was attacked in the way he was by his father by a stranger, they would be in jail in a heartbeat. But it’s not that simple when it’s a family.

My agent really helped me as I was writing the book. She said, “Alice, you’re gonna have to write the love story.” Of course, at that time, I was, “Ugh!” I so don’t want to write that love story. But it really is important to tell the whole story because these are people that you have loved and you have lived with, that you’ve had a life with.

When we look for reasons why these things happen, it’s really important to understand that abusers are often very attractive people. There are often very interesting.

A lot of times abusers are charming and highly intelligent and well-loved in their community. From the outside [looking] in, other people don’t understand the true danger of it. Yeah.

What do you think we as fellow bystanders, as neighbors, can do for each other? How can we help end this cycle?

I think as we go forward people become more and more aware about domestic violence and how it works. I’ll never forget one day shortly after the court, still in Mississippi, the court removed my ex from the house and we were back living in the house. Our driveway was next to our neighbor’s driveway. The woman who lives next door to me said, “Well, it can’t be all that bad. People love him.” I said, “Well, actually, he tried to kill me,” and she said, “But that was one night.”

If you know someone in your life, whether it’s a neighbor or a friend, it’s never one night. It’s ongoing and it stops and starts.

I’m wondering what you think when you see these stories in the news of very high profile, very successful men who are winning Grammys and who are playing in the NFL and are directing films and starring in films. It is very well documented that they have abused their partners. That seems to somehow get forgiveness. That seems to somehow get a pass. What do you think when you see that?

First of all, whenever those stories rise up, it’s like the storm coming. It’s like a hurricane coming in. The first few stories are allegations that maybe this happened. Then it really will reach a crescendo and there are stories about exactly what they did, but are almost in the next moment simultaneous about what is wrong with the person who was the victim.

And that’s exactly what happens in courts with domestic abuse survivors and victims. I think that people are able to allow that forgiveness because they don’t or they can’t acknowledge the real danger. When you hear people talking about domestic violence in a famous NFL player, you never hear someone say, “Well, this could lead to him killing her.” You’re not allowed to say that. But for my perspective, I always see that.

I’m wondering now in the aftermath of these most recent terrible storms and those still to come, what do you want people to know about these kinds of events and the relationship between them and family violence?

Well, it’s almost like the storm becomes a holiday. Everybody knows about intimate partner violence, that the holidays are often a perfect storm. Emotions are heightened, everything feels very do or die, and the storms are similar to a holiday in that kind of relationship.

If there is a hint of violence, if there has been the kernel of violence, then when that storm hits, it’s all going to be amplified and explode and it becomes a very dangerous time. It can also be very isolating. Sometimes people feel like when the catastrophe around them is so great, that their crisis is small, and it’s not. No matter how they feel it’s small in comparison, they deserve to find safety. They deserve to be taken seriously. They deserve to find shelter.

Portions of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Shares