While Donald Trump himself may be an incompetent dunderhead “who insists on taking his intelligence briefings in picture-book form,” as Ta-Nehisi Coates recently wrote, the tragic reality is that he has managed to pack his administration with highly competent supervillains. Many of these people are highly effective at imposing their reactionary worldview on America. This is particularly true on two fronts that are dear to the elderly orange Biff in the Oval Office: Enshrining racial inequality and dismantling environmental protections.

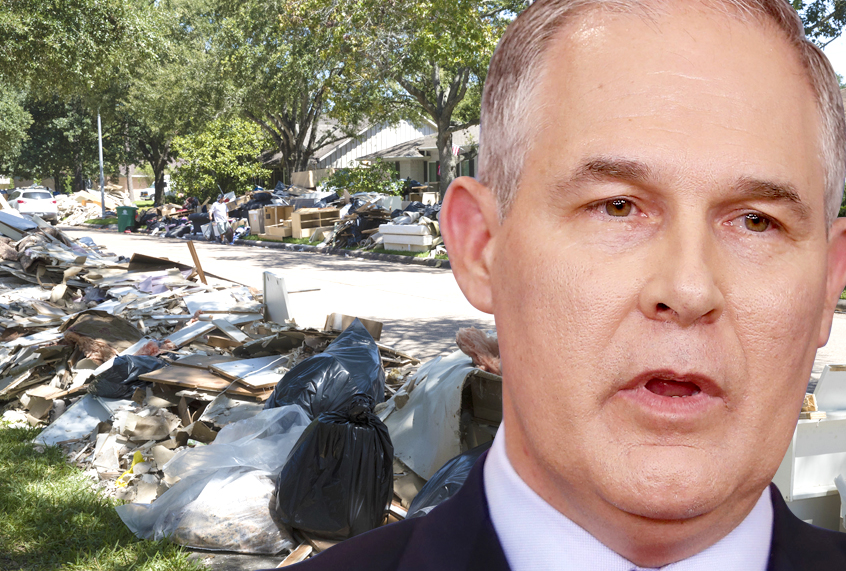

The two issues of social justice and environmentalism have more overlap than many people realize, which has given the Trump administration an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone, rolling back environmental protections while also increasing racial and social inequities. A new report from the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative (EDGI, pronounced “edgy”) details how the Trump administration, primarily the Environmental Protection Agency under Scott Pruitt, has been trying to undo gains made by the environmental justice movement, which focuses on how to rectify the disproportionate impact of pollution and environmental damage on marginalized populations.

While the environmental justice movement has been around for decades, it recently surged into mainstream attention with the protests around the Dakota Access Pipeline, led by members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe who pointed out that the pipeline was threatening their water supply, while bypassing nearby communities that happened to be largely white.

“Enforcement of existing environmental laws doesn’t happen equally,” explained Lindsey Dillon, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. The environmental justice movement rose up as an effort to make sure low-income and other marginalized communities have equal access to government initiatives to reduce pollution and ensure cleaner air and water, among other things.

The EDGI report outlines how, in its first nine months in office, the Trump administration was able to do significant amount of damage to hard-won gains made by the environmental justice movement. The Dakota Access Pipeline project, which President Barack Obama tried to block at the last minute, was allowed to move forward. Regulations meant to protect or at least warn workers and communities exposed to toxic chemicals were rolled back, a move that had implications for communities affected by toxic pollution emitted in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. And Pruitt reversed a ban on agricultural use of chlorpyrifos, a pesticide so toxic it was banned for residential use 17 years ago.

“We all don’t want pesticides in our food,” Dillon explained, “but there’s a different kind of exposure” for farm workers that actually have to be in the fields all day with this stuff, as well as the people who live near fields sprayed with toxic pesticides and the families of farm workers who are exposed when they come home.

Pruitt has also undertaken an alarming effort to restructure the EPA in a way that will almost certainly result in a reducing of activities aimed to address the fact that certain communities are far more likely to suffer toxic environments. Programs that help ameliorate these problems are being targeted for budget cuts, and, alarmingly, there’s been an effort to shut down the office of environmental justice.

Britt Paris, a Ph.D. candidate in the department of information studies at UCLA who co-authored the report, explained that “at the EPA and across a number of government agencies, under the Civil Rights Act,” officials are supposed to consider the effect of their decisions on “the most vulnerable and systematically disadvantaged communities.”

In 1994, President Bill Clinton signed an executive order requiring all federal agencies to “make achieving environmental justice part of [their] mission” by making sure policies resisted “disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects on minority populations and low-income populations.”

Eventually, the office of environmental justice was created. In his interview with EDGI, the former head of the office, Mustafa Ali, described it as “a central place in the government where communities can go, and which can help them navigate this huge bureaucracy that exists” and also “an intersection point so that they can engage with folks and begin to have conversations about environmental issues, and not only the impacts on our communities, but also to help make real change happen.”

Ali, who had worked at the EPA for 24 years, resigned in protest in March, angry over Trump’s proposal to drastically reduce the size of the agency.

These little pieces, considered separately, may not seem like a big deal. But taken together, they paint a troubling picture of an administration that, through its desire to slash regulations and its racial insensitivity (or worse), is willing to allow a surge in pollution-related health problems in communities that are already more likely to be exposed to environmental toxins. Children, in particular, are likely to be affected by this, as is most clearly demonstrated by the racial disparities in childhood asthma rates.

Trump promised he would bring more efficiency to the government. Unfortunately, that seems to mean his administration will maximize efficiency by aiding polluters while screwing over poor communities of color at the same time.