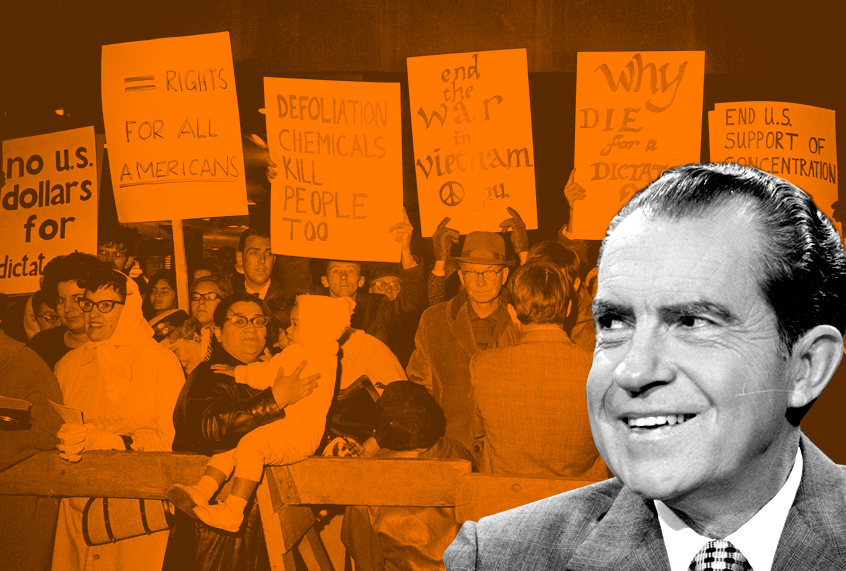

“I want them to break those windows up at the Capitol, I think,” said the president of the United States. Richard Nixon had been elected in 1968 on a law-and-order platform, and he was talking about demonstrators coming to protest him and the Vietnam War, but he privately welcomed the violence. It was more unpopular than the war, so Nixon could use it to his political advantage — for example, to tar peaceful antiwar protestors with the crimes of the violent. When his chief of staff read him a poll on the protests (28 percent in favor, 65 percent opposed), Nixon said, “Make a note there: Take on the fucking demonstrators.”

Nixon was a master of the dark art of orchestrating political tensions, resentments and animosities for maximum political gain. The divisions he sowed in America have never entirely healed. “The divisive country we live in today? It starts with Vietnam,” said filmmaker Ken Burns. In the ninth episode of “The Vietnam War,” titled “A Disrespectful Loyalty (May 1970–March 1973),” Burns and co-director Lynn Novick illuminate the damage done by a president who saw political advantage in sowing political division. The light shed on this dark part of American history could dispel some of its lingering effects. It might even make it more difficult for another president to play the same tricks on us.

Nixon’s most divisive act was to add four more years to a war he knew he could not win. Prolonging the war guaranteed that the divisions that had opened like wounds in the body politic during the presidency of Lyndon Johnson would just grow larger and more painful. The Nixon years became a time of increasing radicalization on the part of the antiwar movement — and on the part of the anti-antiwar movement. To cite one notorious example, a faction of the Students for a Democratic Society became the Weather Underground, its political activism curdling into political violence. The Weathermen set off bombs in America, hoping to set off a revolution as well. It didn’t work out as planned. Instead, the Weathermen became the perfect villains for a Republican president who wanted to smear the larger, peaceful antiwar movement as violent, radical and anti-American. To cite another notorious example of Nixon-era radicalization, New York construction workers physically attacked antiwar demonstrators in the Hard Hat Riot. Nixon responded by inviting the head of the construction workers union to the White House — and later making him secretary of labor. It helped lure traditionally Democratic voters into Nixon’s New American Majority. Nixon profited from the rise of violence on the left and right, even as it bred fear, distrust and even hatred in America.

If only Americans at that time had gotten the chance to hear the secretly recorded White House tapes that Burns and Novick include in “The Vietnam War.” The tapes would have united America — left, right and center — against Nixon. The tapes reveal the real reason Nixon prolonged the war — a cold, hard political calculation. Nixon assumed that he would lose his reelection bid if South Vietnam fell before Election Day 1972. To avoid being rejected at the polls as a president who lost a war, Nixon kept American troops fighting and dying in Vietnam through all four years of his first term. It was a policy that all patriotic, God-fearing, peace-loving, troops-honoring, war-hating Americans would have gladly joined in opposing, had they but known.

Nixon hid his true thinking. He told us he would end the war through “Vietnamization” or negotiation. He said “Vietnamization” would train and equip South Vietnam to defend itself, so American troops could come home. Before he even announced the “Vietnamization” program, he knew it would not work. On his first full day in office, January 21, 1969, Nixon asked his top advisers how soon South Vietnam would be able to defend itself without American troops. The answer was simple and clear: not for the foreseeable future. The South would depend on American troops for its survival even after it was fully trained and equipped. This was the unanimous view of the Pentagon, CIA, State Department, Joint Chiefs of Staff, American embassy in Saigon and the U.S. military commander in Vietnam. That didn’t stop Nixon from promising to “withdraw all of our forces from Vietnam on a schedule in accordance with our [Vietnamization] program, as the South Vietnamese become strong enough to defend their own freedom.” Nixon knew this wasn’t going to happen. On his own White House tapes, you can hear him say, “I look at the tide of history out there — South Vietnam probably can never even survive anyway.” Vietnamization gave Nixon a chance to stretch out American withdrawal for four years and to claim credit for reducing the number of American soldiers in Vietnam from more than 500,000 when he took office to less than 50,000 by Election Day 1972.

Nixon’s refusal to face the ugly facts (in public at least) enabled opponents and supporters of the war to avoid facing the ugliest aspects of their own positions. Liberals did not like to admit that leaving Vietnam would mean losing the war. Conservatives did not like to admit that staying in Vietnam would mean continued stalemate, not victory. Vietnamization gave all an excuse to avoid confronting unpleasant reality. The cost of that avoidance was not apparent at first.

As Nixon dragged out the war, more and more Americans told pollsters they wanted Congress to make the president bring the troops home by the end of 1971. Nixon considered the idea, but his national security adviser Henry Kissinger privately warned him that Saigon might fall before Election Day as a consequence. Publicly, Nixon framed the issue in terms of national honor and national security. He said, “The issue very simply is this: Shall we leave Vietnam in a way that — by our own actions — consciously turns the country over to the Communists? Or shall we leave in a way that gives the South Vietnamese a reasonable chance to survive as a free people? My plan will end American involvement in a way that would provide that chance. And the other plan would end it precipitately and give victory to the Communists.” Nixon made support for his plan sound strong, loyal and heroic, and opposition sound weak, defeatist and treacherous. His polarizing rhetoric led Democrats to ask if the Republican would ever end the war and conservatives to ask if liberals wanted the Communists to win. And so the divisions deepened, as Americans questioned one another’s sanity, morality and patriotism.

For Nixon, the real issue, very simply, was this: would South Vietnam fall before the 1972 presidential election, or after? When it could hurt Nixon’s chances at winning a second term, or when it would be too late for the voters to hold him accountable? By the spring of 1971, Nixon had settled on a range of possible exit dates that would allow him to both (1) avoid a pre-election South Vietnamese collapse and (2) claim that Vietnamization had succeeded. He thought he could meet both goals if he brought the last troops home any time from July of 1972 to January of 1973. Nixon preferred to do it before the election, when it could do him the most good politically. Kissinger preferred to do it after, when the threat of a pre-election collapse had passed completely.

“Our major goal is to get our ground forces the hell out of there long before the elections,” Nixon said.

“The only problem is to prevent the collapse in ’72,” Kissinger said.

“I know. I know!” Nixon said.

In the end, Nixon fooled liberals and conservatives alike — and used both for his political ends.

Liberals like the 1972 Democratic presidential nominee Sen. George S. McGovern, D-SD sincerely believed that Nixon was committed to preserving South Vietnam. McGovern framed the election as “a choice between four more years of war, or four years of peace.” He overestimated Nixon’s anti-Communism and underestimated his political opportunism. The Democrat was caught flat-footed two weeks before the election when the White House announced that it had reached a settlement with North Vietnam. The agreement called for complete withdrawal of American troops from South Vietnam in return for the release of American prisoners of war from the North — two goals McGovern shared. When South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu refused to sign the deal, McGovern concluded it was some kind of Nixonian trick to keep the war going. McGovern misread the situation completely.

The agreement was a “decent interval” deal. It would only keep South Vietnam going for another year or two before the North took over. It was a way of ensuring that Saigon didn’t collapse a few months after the last American troops left, thereby demonstrating that Vietnamization was a failure and that Nixon had sacrificed the lives of more than 20,000 American soldiers in vain. “We’ve got to find some formula that holds the thing together a year or two,” Kissinger said. “After a year, Mr. President, Vietnam will be a backwater. If we settle it, say, this October, by January ’74 no one will give a damn.” Nixon and Kissinger justified the “decent interval” exit strategy by telling themselves that it preserved American credibility. “If a year or two years from now North Vietnam gobbles up South Vietnam, we can have a viable foreign policy if it looks as if it’s the result of South Vietnamese incompetence.” In order to get the deal, Nixon and Kissinger secretly assured the Communists that America would not intervene again, as long as the North waited a year or two before taking over the South. Nixon was willing to forfeit America’s credibility with our Cold War adversaries to preserve his political credibility with American voters.

South Vietnam rejected the deal for the same reason North Vietnam accepted it — both realized that it would lead to Saigon’s fall, as I wrote in “Fatal Politics: The Nixon Tapes, the Vietnam War, and the Casualties of Reelection.” The deal would leave 150,000 North Vietnamese troops in South Vietnam — precisely the kind of threat that the South could not handle on its own, as Nixon’s military, diplomatic and intelligence advisers had warned him. Briefed on Nixon and Kissinger’s settlement terms, President Thieu had wept angry tears and said the deal meant suicide for the South. The Saigon government united in opposition. “These guys are scared. And they’re desperate. And they know what’s coming,” Kissinger said. “And Thieu says that, sure, this — these proposals keep him going, but somewhere down the road he’ll have no choice except to commit suicide. And he’s probably right.”

This was the same Kissinger who went before the White House cameras when North Vietnam accepted the deal and said, “We believe that peace is at hand.” The agreement was not the “peace with honor” that Nixon had promised. It was delayed defeat concealed by deceit.

But it sure worked politically. Nixon won reelection in a record-setting landslide with 60.7 percent of the popular vote and the electoral votes of 49 states. This looked like an enormous win for conservatives, but in retrospect the victory seems hollow. Conservatives thought they were supporting a strong leader who put American interests before his political interest, who stuck with an unpopular war despite great domestic opposition, and was vindicated when the enemy accepted his settlement demands. In reality, Nixon’s settlement demands set the stage for Communist victory as soon as a “decent interval” passed; he prolonged an unpopular war because he calculated that losing it would be even more unpopular, and he did this because he put his political interests above American interests and all other values. Prolonging the war brought with it a host of social ills: domestic division, civil disorder, reduced respect for the law, diminished morale and increased drug abuse in the armed forces. It cost the lives of more than 20,000 American soldiers and countless more Vietnamese, North and South. A true conservative could make a case for waging war to prevent a Communist victory in Vietnam, but not merely to prevent a Democratic victory in the United States. No one deserved to die for that, American or Vietnamese, Communist or anti-Communist. Nixon’s victory depended on dividing Americans and defiling the fundamental values that unite us as a people, conservative values as well as liberal ones.

To avoid taking responsibility for the consequences of his “decent interval” exit strategy, Nixon blamed the fall of Saigon on liberals in Congress. Specifically, he blamed Congress for providing less aid to the South than the president requested (true) and for prohibiting the use of American airpower in Indochina (true, though Congress did this only after Nixon said he would sign the prohibition into law). Long before Congress took either of these steps, however, Nixon’s own settlement terms doomed Saigon to fall, something that was understood at the time by Nixon and Kissinger, Moscow and Beijing, North and South Vietnam. Nevertheless, Nixon’s stabbed-in-the-back myth, the most divisive and destructive kind of historical delusion, lives on in works like Lewis Sorley’s highly influential book, “A Better War: The Unexpected Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam.” True believers in the myth should check out Sorley’s earlier, more balanced, book, “Thunderbolt: General Creighton Abrams and the Army of His Times.” In Thunderbolt, Sorley writes that Saigon “was asked to sign on to an agreement that would sanction the continuing presence in the South of hundreds of thousands of invading troops. Agonizing as it was, their ouster had proven too difficult to attain, no less so in Paris than on the battlefield. Thieu sensed — correctly — that a ceasefire in place foreshadowed the eventual downfall of an independent South Vietnam. Henry Kissinger maintained — perhaps also correctly — that he got the best agreement possible under the circumstances. In that gap between what was necessary and what was attainable lay the essential tragedy of the war in Vietnam.” This is a valuable unlearned lesson of the war. We lost because our most capable civilian and military leaders never figured out a way to win.

Some of our leaders, the worst of them, turned us against one another to conceal their own failures. We should never let them do that to us again.

Read more from the University of Virginia Press.