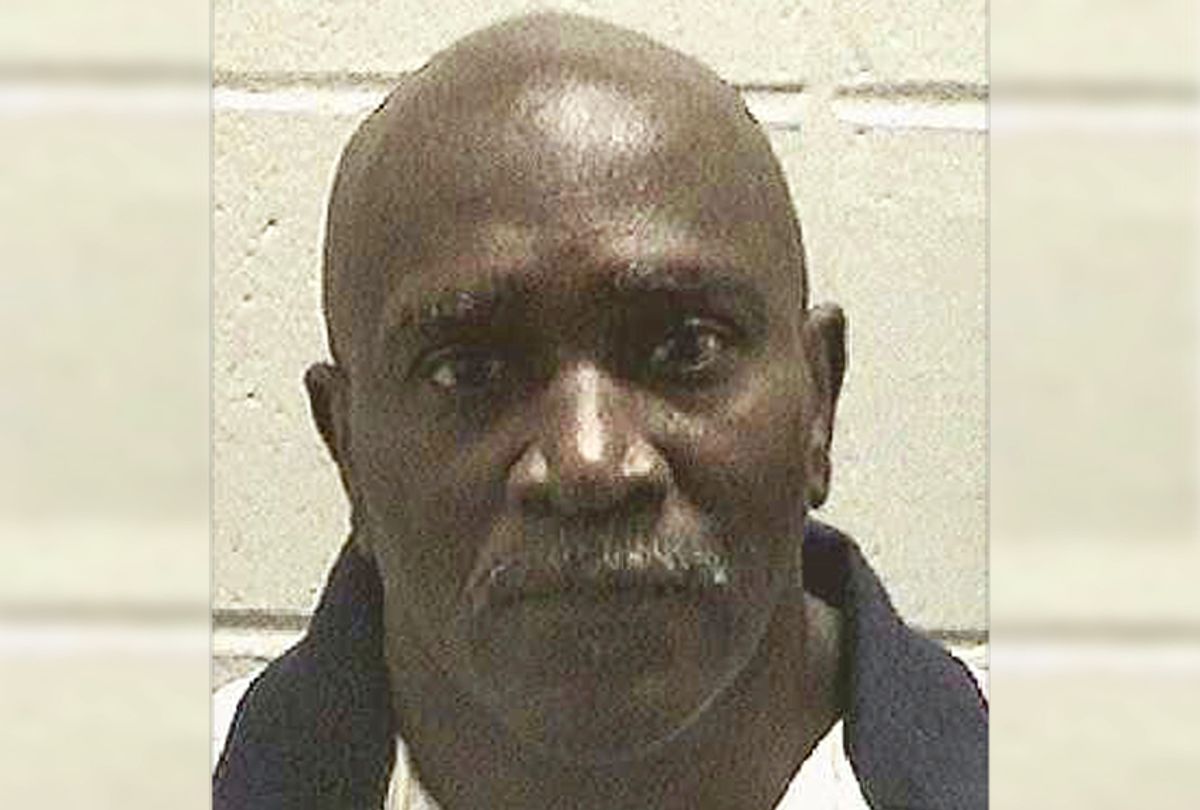

Seven years after a jury unanimously sentenced Keith Tharpe to death for the 1990 murder of his sister-in-law, one white juror revealed to Tharpe’s lawyers the stunning racial bias he applied to the capital sentence case.

“After studying the Bible, I have wondered if black people even have souls,” Barney Gattie told Tharpe’s lawyers, who were conducting a routine review of the case. Gattie, who is now deceased, elaborated further in a signed affidavit: "In my experience, I have observed that there are two types of black people. 1. Black folks and 2. Niggers."

Gattie understood some people did not like the N-word but he "tells it like he sees it," one of Tharpe's lawyers told the court the next day. In their 1998 court filing, lawyers for Tharpe said the white juror “possessed profoundly racist views” and repeatedly used racial slurs during deliberations to describe Tharpe.

Gattie reportedly talked about kicking “niggers” who “act up” out of the store he owned and randomly opined on the O.J. Simpson case, asserting that the “white woman … wouldn’t have been killed if she hadn’t have married that black man.”

Gattie also admitted that he knew the murder victim in the case, Jacquelin Freeman -- a clear conflict of interest, sufficient to get most convictions thrown out -- and called her family "nice black folks." He said that Tharpe, however, wasn't in the "good black folks category" and that he deserved the electric chair for what he did to Freeman, adding that if the Freemans had been "the type Tharpe is" then choosing between life and death for Tharpe "wouldn't have mattered so much." (Georgia used electrocution to carry out executions at the time, but now uses lethal injection.)

Tharpe's legal defense team has argued that he is intellectually disabled. He never denied killing the sister of his estranged wife. Violating a court order to stay away from the mother of his four children, Tharpe confronted his wife and sister-in-law as they drove to work, according to court documents. Fueled by rage, alcohol and cocaine, Tharpe blocked their car, took out a shotgun and repeatedly shot Freeman.

Three months later, he was sentenced to death.

This is not a story of an innocent man wrongly executed by the state. It is a story about a state so driven to execute a man that it willfully ignored clear violations of due process and equal protection and barely made any pretense of giving him a fair trial. What happens to the right to an “impartial jury” for a black defendant when one of the 10 white jurors calls him a “nigger"? Does guilt or innocence matter when clear patterns of racism are found in the application of criminal justice?

State lawyers met Gattie two days after he signed the 1998 affidavit. In a new statement, Gattie insisted that he was drunk when he spoke to Tharpe’s lawyers and claimed he didn’t realize how his words could be used to re-examine the verdict and the death sentence. Notably, he did not deny any of his sworn statements regarding his opinions of black people in general or Keith Tharpe in particular.

Only a unanimous jury can convict and impose a death sentence in Georgia. While the law allows for misconduct by a single juror as grounds to reopen a case, it prohibits courts from reviewing any jury testimony that impeaches the verdict and requires a new trial -- even if there is evidence that one or more jurors used racially biased decision-making.

But a March 2017 U.S. Supreme Court ruling found that the "no impeachment" rule should be invalidated when "a juror makes a clear statement that indicates he or she relied on racial stereotypes or animus to convict a criminal defendant." In a 5–3 decision, the justices ruled that it “must become the heritage of our Nation to rise above the racial classifications that are so inconsistent with our commitment to the equal dignity of all persons.”

Advocates have argued that Tharpe is not the same man who shot Freeman three times with a shotgun. Tharpe, known to friends and family as Bo, has since expressed regret for his "terrible decisions and actions" that led to his sister-in-law's death.

On Monday, the 27th anniversary of Freeman’s death, the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles denied Tharpe’s clemency petition. Last year, Georgia carried out nearly half the executions in the United States.

Tharpe, now 59 years old, had more than 20 friends, relatives, religious counselors and attorneys appear before the Georgia board to ask for clemency. They declined, and on Tuesday the Georgia Supreme Court refused to hear his appeal, voting 6-3 that other courts had already responded to these issues. That left the U.S. Supreme Court as Tharpe's last option. Just last year the high court allowed the execution of another Georgia man whose jury included one juror who later revealed in a sworn affidavit: “I don’t know if he killed anybody,” but the death penalty was “what that nigger deserved.”

Just before 11 pm Tuesday night, the U.S. Supreme Court granted Tharpe a stay of execution, three and a half hours after he was scheduled to be put to death by legal injection.

His case is yet more proof of how flawed the administration of the death penalty is in the United States. There are currently more than 2,800 inmates on death row, roughly 95 percent of whom are poor. The Death Penalty Information Center found that the odds of a death sentence were 97 percent higher for black people in some places. Even though African-Americans make up only 13 percent of the total population, 35 percent of those executed since 1976 have been black.

Shares