Fifty years after the desegregation of America’s lunch counters, the time has come to integrate our public history memorials, to counter or replace our Confederate monuments with projects that honor America’s less celebrated black heritage.

But the planners in Richmond, Virginia, who are trying to create a monument to honor those black Virginians who fought for freedom, are facing a dilemma: Should they include Nat Turner on the monument?

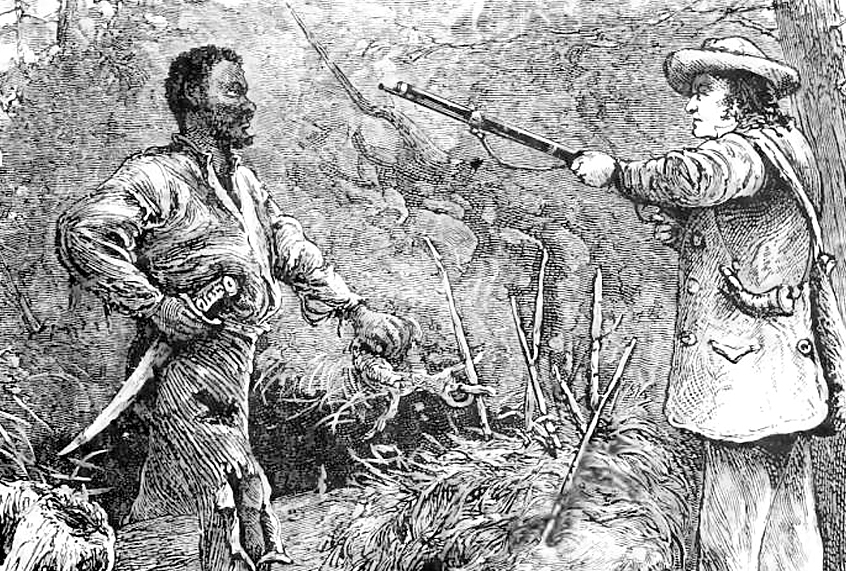

Yes, Turner was the leader of the largest and most important slave revolt in Virginia history. It established his incalculable value as an icon of abolitionism and black resistance. Yet that same revolt led to the death of 55 whites, many of them women and children.

The most deadly raid during the revolt occurred on Aug. 22, 1831, at the house of Levi Waller, who escaped the rebels only to witness the killing of his wife and 10 children, some of whom attended a school that was held on his farm.

Given this, should Turner be memorialized?

As someone who has written the most recent book on the Nat Turner Revolt, I think that there is no easy way to avoid this dilemmas. After all, it seems willfully misleading to try to compose a list of the Virginians who fought slavery and ignore Virginia’s most important and best documented freedom fighter. That’s like making a list of the great singers from Memphis but leaving off Elvis.

But it won’t do to ignore the fact that the rebels decided to kill women and children, the beneficiaries but not the agents of slavery.

Turner himself implied that this was not the way that he wanted to fight. After he was captured, Turner insisted that once the rebels armed a “sufficient force,” they planned to spare women, children, and even “men too who ceased to resist.” Although some rebels were looking for revenge, Turner himself was no bloodthirsty fanatic.

And this is where Turner’s example helps illustrate the tragedy of slavery better than anyone else. Turner wanted freedom for slaves, but he lived in a world where there was no obvious thing he could do that would lead to freedom. Virginia’s whites were too committed to it.

Accepting a his fate — or even fighting against it within the conventional rules of war — would have spared the lives of dozens of whites, but it would have left unchallenged a system of bondage that countenanced brutality, the separation of families, rape and even murder. As far as Turner could tell, it might have meant another 15 generations of slavery. Turner refused to accept that.

Turner was obviously bright man. The man who wrote down his confessions observed that his “natural intelligence and quickness of apprehension is surpassed by few men I have ever seen.” Given that, his agreement to launch an attack that began with indiscriminate killing might be seen as a canny strategic choice — a way to arouse the black population to join the revolution en masse. Turner understood that his plan might not work, but it was worth a try.

As it happened, the plan almost did work, but not in the way that Turner had imagined. Killing women and children did not help rally slaves and free blacks to the rebels’ banner, so his revolt was put down quickly.

Yet, it did have impact beyond its short life. The killings scared the dickens out of many of Virginia’s whites and, in the months after the revolt, thousands of white men and women petitioned Virginia’s House of Delegates to do something about the danger that lurked in Virginia’s households. After debate, the Virginia legislature ultimately decided not to end slavery. Yet the vote was surprisingly close.

No one else came as close as Nat Turner to setting Virginia on a path to freedom before the Civil War. Located to a time and place, his revolt was not simply an extraordinary, albeit bloody, bid for freedom, it was one that nearly solved the single greatest political problem in Virginia’s history.

Across the ages, Turner’s is a searing image the righteous rage of America’s oppressed blacks, of the crimes of the oppressors, of the kind of things those crimes can make us do.

Perhaps it is unpleasant to think about what the rebels did as they fought against our nation’s original sin — but it is better to think about than to ignore. Our history is not an easy one. Spinning it into monuments shouldn’t be either.