For an adult, it’s confusing and appalling to see your people lose freedoms as society spirals into chaos and totalitarianism. Imagine what it’s like for a child.

Actually, no need to imagine. Just read “Poppies of Iraq” — by Brigitte Findakly and Lewis Trondheim. This graphic novel is a plainly stated, emotionally devastating memoir of Findakly’s life as a Christian girl in Iraq and her relationship to that country after moving to France. The details of Findakly’s life (illustrated by her cartoonist husband Trondheim) will be fascinating to anyone interested in Iraq before and after the rise of Saddam Hussein. But “Poppies of Iraq” hits even harder because it’s a relatable story about growing up anywhere in this baffling world.

All kids kick balls and climb whatever they can: Findakly just happened to spend her carefree childhood moments messing around on the ruins of Mosul, which were demolished in 2015 by Daesh, The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Findakly didn’t fully realize the historic important of the site at the time, and she certainly didn’t realize its days were numbered: “It was the perfect spot for climbing on ancient stones. And for picking poppies.” The destruction of these ruins — culturally important to Iraqis and personally important to Findakly — was the impetus for this book, which was originally published in French.

This graphic novel is, to use a trite phrase, a “coming-of-age story,” but it’s a lot more than that.

Findakly’s words and Trondheim’s images show what it was like for a young Christian girl to grow up in Iraq from her 1959 birth until 1973, when her family moved to France. “Poppies of Iraq” is about Findakly’s evolving relationship with Iraq, a place she’ll always love but became progressively estranged from, thanks to a succession of repressive regimes and her own awakening as a feminist.

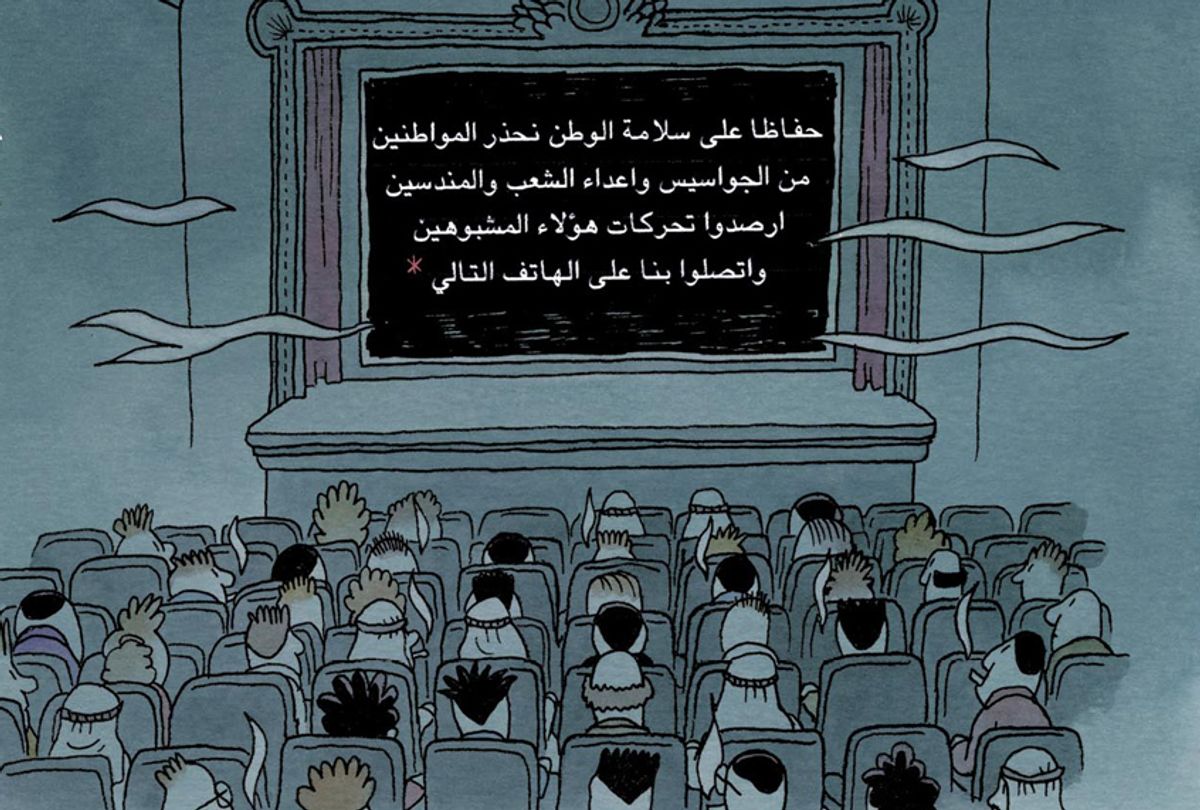

When Findakly did return after moving to France, each trip became more and more painful, especially as Findakly saw how her extended family suffered under governmental insanity (pictures of Saddam Hussein were mandatory in every home, while children were taught pro-Saddam songs) and terrible shortages (there’s a depressing anecdote involving the scarcity of apples). These details are as important to the life of Iraq as the life of Findakly. In addition to being an engrossing memoir, this is an impressive work of journalism.

Like any great comic, even one about the real world, “Poppies of Iraq” creates its own reality for readers to get lost in — a world told via plain, blunt language and non-realistic, cartoony figures that interweave the personal and political. One of the most subtly brutal sequences in the book involves a marriage. In a tense two pages, Trondheim presents three short conversations consisting of the words “So?” and “Completely.” The three conversations are relaying some unclear information from a man to another man, that man to a woman, and then that woman to another woman. The meaning of these simple words is eventually made clear: in Iraq, a husband has the right to demand his bride remove all pubic hair before the wedding, and these two pages show that information being carried from groom to bride. The simple fact of male power over women is awful, but Trondheim’s subtle cartooning makes this sequence particular and devastating. This kind of graphic power is on display through “Poppies for Iraq.”

Some scenes are reminiscent of a Seinfeld episode, showing that even among frequent coups and mounting oppression, the Larry Davidian aspects of life never go away. Findakly and Trondheim show the culture clash between her French mother and native Iraqis in many ways, but most memorably in a difference in manners. Findakly’s mom often made delicious French pastries, but it’s an Iraqi custom to turn down seconds unless asked again, which was not the French way. As Findakly dryly puts it, “It was the guests who finally changed their ways when they came to visit.” Makes sense. Customs are important, but French pastries come first. This humorous episode takes on additional absurdity when the subject shifts to a military coup on the next page. Few comics make better use of juxtaposition.

Trondheim tells the story with a six-panel format, creating a strong visual rhythm: the big blocks of the six panels feel like large bricks coming down one by one, as Findakly’s life eventually flourishes in France while Iraq’s society deteriorates. Trondheim’s art is made of clear lines and tiny, cartoony figures that emphasize the smallness of a child — and the relative smallness of everyone when the world is spinning out of control. The art is interrupted occasionally by photos of Findakly’s family, emphasizing the nonfiction nature of this book. Actual pictures of Findakly as a little girl, her father in his dentists’ office, and the ruins of Mosul are a strong counterpoint to Trondheim’s art.

As the book wraps up, Findakly narrates the continued deterioration of Iraq and her loss of ties to home, as her family members all end up emigrating elsewhere (some becoming stubbornly Islamophobic, much to Findakly’s sadness). As Findakly discusses the present-tense of her life and Iraq in the usual six-panel pages, Trondheim switches up the visual format on other pages: these feature full-page panels accompanied by Findakly’s good memories of Iraq. This is an effective and moving way to end the book and show the power of childhood. The present is imprisoned in tiny, constricted panels, but the past is an expansive place that can’t be erased.

Throughout this bittersweet book, Findakly and Trondheim interweave the political and personal in a way that mirrors and heightens real life. “Poppies of Iraq” is about big events as seen through small eyes: there’s a universalness underneath the specificity. Anyone, even with a boring childhood, should find something to relate to here. No child asked for their particular family or circumstances: no child (or maybe adult) truly understands what’s going on around them or why the world is the way it is. This is an unforgettable, devastating, sweet book.

Shares