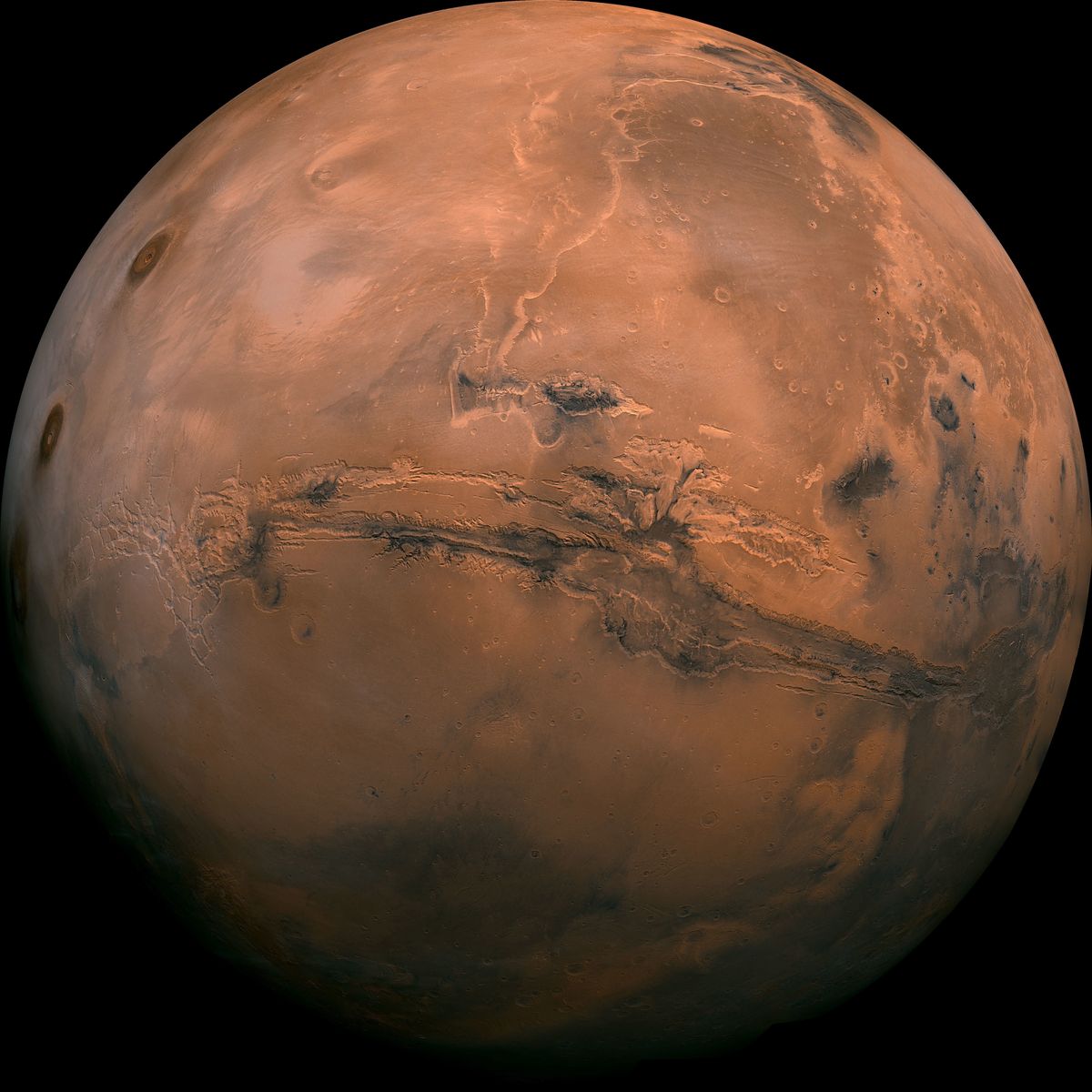

Elon Musk has a plan, and it’s about as audacious as they come. Not content with living on our pale blue dot, Musk and his company SpaceX want to colonize Mars, fast. They say they’ll send a duo of supply ships to the red planet within five years. By 2024, they’re aiming to send the first humans. From there they have visions of building a space port, a city and, ultimately, a planet they’d like to “geoengineer” to be as welcoming as a second Earth.

If he succeeds, Musk could thoroughly transform our relationship with our solar system, inspiring a new generation of scientists and engineers along the way. But between here and success, Musk and SpaceX will need to traverse an unbelievably complex risk landscape.

Many will be technical. The rocket that’s going to take Musk’s colonizers to Mars (code named the “BFR” — no prizes for guessing what that stands for) hasn’t even been built yet. No one knows what hidden hurdles will emerge as testing begins. Musk does have a habit of successfully solving complex engineering problems though; and despite the mountainous technical challenges SpaceX faces, there’s a fair chance they’ll succeed.

As a scholar of risk innovation, what I’m not sure about is how SpaceX will handle some of the less obvious social and political hurdles they face. To give Elon Musk a bit of a head start, here are some of the obstacles I think he should have on his mission-to-Mars checklist.

AP Photo/Refugio Ruiz

Planetary protection

Imagine there was once life on Mars, but in our haste to set up shop there, we obliterate any trace of its existence. Or imagine that harmful organisms exist on Mars and spacecraft inadvertently bring them back to Earth.

These are scenarios that keep astrobiologists and planetary protection specialists awake at night. They’ve led to unbelievably stringent international policies around what can and cannot be done on government-sponsored space missions.

Yet Musk’s plans threaten to throw the rule book on planetary protection out the window. As a private company SpaceX isn’t directly bound by international planetary protection policies. And while some governments could wrap the company up in space bureaucracy, they’ll find it hard to impose the same levels of hoop-jumping that NASA missions, for instance, currently need to navigate.

It’s conceivable (but extremely unlikely) that a laissez-faire attitude toward interplanetary contamination could lead to Martian bugs invading Earth. The bigger risk is stymying our chances of ever discovering whether life existed on Mars before human beings and their grubby microbiomes get there. And the last thing Musk needs is a whole community of disgruntled astrobiologists baying for his blood as he tramples over their turf and robs them of their dreams.

Ecoterrorism

Musk’s long-term vision is to terraform Mars — reengineer our neighboring planet as “a nice place to be” — and allow humans to become a multi-planetary species. Sounds awesome — but not to everyone. I’d wager there will be some people sufficiently appalled by the idea that they decide to take illegal action to interfere with it.

Vail Fire Department

The mythology surrounding ecoterrorism makes it hard to pin down how much of it actually happens. But there certainly are individuals and groups like the Earth Liberation Front willing to flout the law in their quest to preserve pristine wildernesses. It’s a fair bet there will be people similarly willing to take extreme action to stop the pristine wilderness of Mars being desecrated by humans.

How this might play out is anyone’s guess, although science fiction novels like Kim Stanley Robinson’s “Mars Trilogy” give an interesting glimpse into what could transpire once we get there. More likely, SpaceX will need to be on the lookout for saboteurs crippling their operations before leaving Earth.

Space politics

Back in the days before private companies were allowed to send rockets into space, international agreements were signed that set out who could do what outside the Earth’s atmosphere. Under the United Nations Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, for instance, states agreed to explore space for the benefit of all humankind, not place weapons of mass destruction on celestial bodies and avoid harmful contamination.

That was back in 1967, four years before Elon Musk was born. With the emergence of ambitious private space companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin and others, though, who’s allowed to do what in the solar system is less clear. It’s good news for companies like SpaceX – at least in the short term. But this uncertainty is eventually going to crystallize into enforceable space policies, laws and regulations that apply to everyone. And when it does, Musk needs to make sure he’s not left out in the cold.

This is of course policy, not politics. But there are powerful players in the global space policy arena. If they’re rubbed the wrong way, it’ll be politics that determines how resulting policies affect SpaceX.

Climate change

Perhaps the biggest danger is that Musk’s vision of colonizing Mars looks too much like a disposable Earth philosophy — we’ve messed up this planet, so time to move on to the next. Of course, this idea may not factor into Musk’s motivation, but in the world of climate change mitigation and adaptation, perceptions matter. The optics of moving to a new planet to escape the mess we’ve made here is not a scenario that’s likely to win too many friends amongst those trying to ensure Earth remains habitable. And these factions wield considerable social and economic power — enough to cause problems for SpaceX if they decide to mobilize over this.

There is another risk here too, thanks to a proposed terrestrial use of SpaceX’s BFR as a hyperfast transport between cities on Earth. Musk has recently titillated tech watchers with plans to use commercial rocket flights to make any city on Earth less than an hour’s travel from any other. This is part of a larger plan to make the BFR profitable, and help cover the costs of planetary exploration. It’s a crazy idea — that just might work. But what about the environmental impact?

Even though the BFR will spew out tons of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, the impacts may not be much greater than current global air travel (depending how many flights end up happening). And there’s always the dream of creating the fuel — methane and oxygen — using solar power and atmospheric gases. The BFR could even conceivably be carbon-neutral one day.

But at a time when humanity should be doing everything in our power to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, the optics aren’t great. And this could well lead to a damaging backlash before rocket-commuting even gets off the ground.

AP Photo

Inspiring — or infuriating?

Sixty years ago, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite – and changed the world. It was the dawn of the space age, forcing nations to rethink their technical education programs and inspiring a generation of scientists and engineers.

We may well be standing at a similar technological tipping point as researchers develop the vision and technologies that could launch humanity into the solar system. But for this to be a new generation’s Sputnik moment, we’ll need to be smart in navigating the many social and political hurdles between where we are now and where we could be.

These nontechnical hurdles come down to whether society writ large grants SpaceX and Elon Musk the freedom to boldly go where no one has gone before. It’s tempting to think of planetary entrepreneurialism as simply getting the technology right and finding a way to pay for it. But if enough people feel SpaceX is threatening what they value (such as the environment — here or there), or disadvantaging them in some way (for example, by allowing rich people to move to another planet and abandoning the rest of us here), they’ll make life difficult for the company.

![]() This is where Musk and SpaceX need to be as socially adept as they are technically talented. Discounting these hidden hurdles could spell disaster for Elon Musk’s Mars in the long run. Engaging with them up front could lead to the first people living and thriving on another planet in my lifetime.

This is where Musk and SpaceX need to be as socially adept as they are technically talented. Discounting these hidden hurdles could spell disaster for Elon Musk’s Mars in the long run. Engaging with them up front could lead to the first people living and thriving on another planet in my lifetime.

Andrew Maynard, Director, Risk Innovation Lab, Arizona State University

Shares