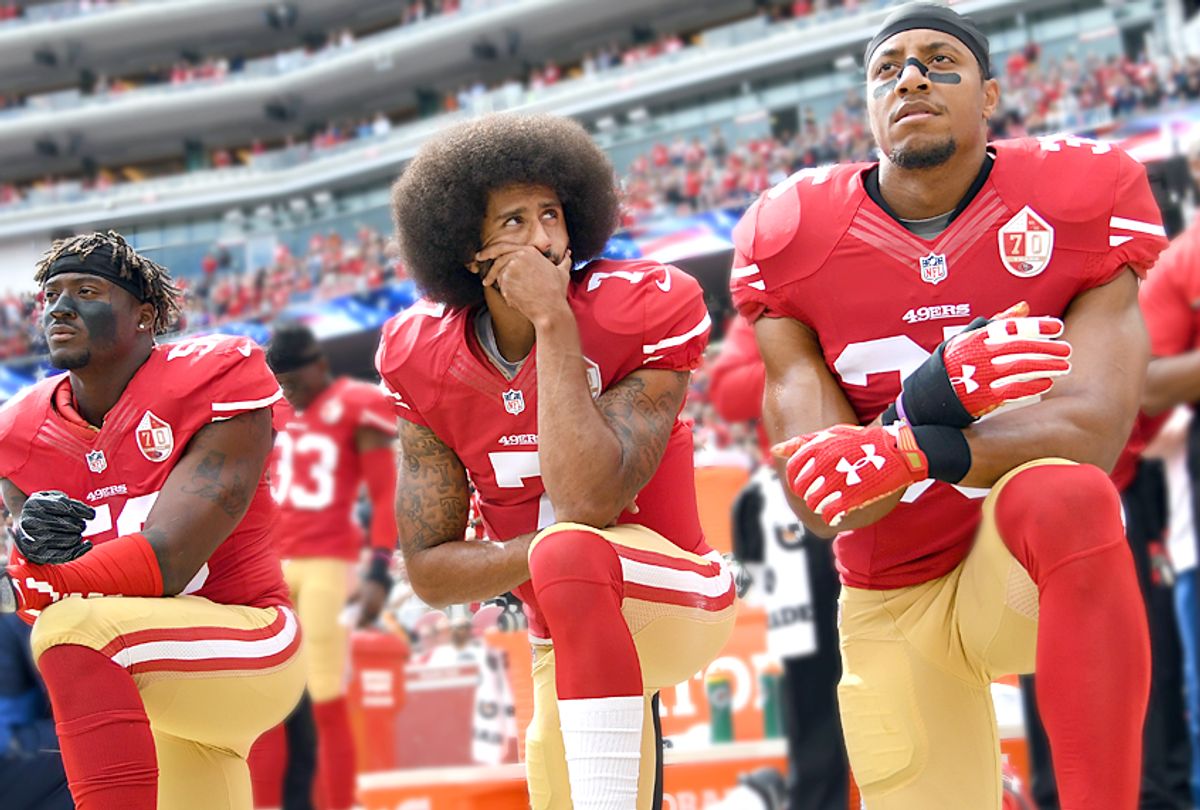

When NFL player Colin Kaepernick refuses to stand for the national anthem, or the cast of the Broadway musical “Hamilton” confronts the vice president-elect, or the Dixie Chicks speak out against war, talk quickly turns to freedom of speech. Most Americans assume they have a constitutional guarantee to express themselves as they wish, on whatever topics they wish. But how protected by the First Amendment are public figures when they engage in political protest?

Coming out publicly, whether for or against some disputed position, can have real consequences for the movement and the celebrity. However helpful a high-profile endorsement may be at shifting the public conversation, taking these public positions – particularly unpopular ones – may not be as protected as we assume. As a professor who studies the intersection of law and culture, I believe Americans may need to revisit their understanding of U.S. history and the First Amendment.

Harnessing the power of celebrity

Far from being just product endorsers, celebrities can and do use their voices to influence policy and politics. For example, some researchers believe Oprah Winfrey’s early endorsement of Barack Obama helped him obtain the votes he needed to become the 2008 Democratic nominee for president.

This phenomenon, however, is not new.

Joseph-Désiré Court

Since the birth of the nation, celebrities have used their voices – and had their voices used – to advance important causes. In 1780, George Washington enlisted the help of Marquis de Lafayette, a French aristocrat dubbed by some “America’s first celebrity,” to ask French officials for more support for the Continental Army. Lafayette was so popular that when he traveled to America some years later, the press reported on each day and detail of his yearlong visit.

Social movements also have harnessed the power of celebrity influence throughout American history. In the early 1900s, after the National Woman Suffrage Association was founded to pursue the right of women to vote, the group used celebrities to raise awareness of the cause. Popular actresses like Mary Shaw, Lillian Russell and Fola La Follette, for example, brought attention to the movement, combining their work with political activism to push the women’s suffrage message.

Celeb actions can move the needle

The civil rights movement of the 1960s benefited from celebrities’ actions. For instance, after Sammy Davis Jr., a black comedian, refused to perform in segregated venues, many clubs in Las Vegas and Miami became integrated. Others – including Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, Dick Gregory, Harry Belafonte, Jackie Robinson and Muhammad Ali – were instrumental in the success of the movement and passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. These actors planned and attended rallies, performed in and organized fundraising efforts and worked to open opportunities for other black people in the entertainment industry.

By the 1980s, you could watch Charlton Heston and Paul Newman debate national defense policy and a potential nuclear weapons freeze on television. Meryl Streep spoke before Congress against the use of pesticides in foods. Ed Asner and Charlton Heston publicly feuded about their differing opinions of the Reagan administration’s support of right-wing Nicaraguan militant groups.

Whatever you think of how well thought out their opinions are (or aren’t), celebrities have the ability to draw attention to social issues in a way others do not. Their large platforms through film, music, sports and other media provide significant amplification for the initiatives they support.

There is, in particular, a measurable connection between celebrity opinions and young people. Most marketing research shows that celebrity endorsements can improve the likelihood that young consumers will choose the endorsed product.

Antagonism toward celebrity activism

Celebrities have been important partners, strategists, fundraisers and spokespeople for social movements and politicians since the earliest days of modern America. Recently, however, celebrities speaking out about policy and politics have received some harsh responses.

Kaepernick, in particular, has received scathing criticism. Fans of his team have burned his jersey in effigy. Mike Evans, another NFL player, drew so much criticism for sitting in protest of Donald Trump’s election to the presidency that he was forced to apologize and say he would never do it again. #BoycottHamilton trended on Twitter after the cast of the Broadway show Hamilton addressed Mike Pence.

President-elect Donald Trump jumped into the fray, tweeting that he does not support the public expression of sentiments like those of the “Hamilton” cast.

Unprotected speech

All of this raises significant questions about speech, protests and the law. Often celebrities, commentators and pundits talk about being able to say whatever they want thanks to their right to freedom of speech. But this idea is based on common misconceptions about what the U.S. Constitution actually says.

What is allowed under the law starts with the text of the First Amendment, which provides that:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

The language essentially allows for freedom of expression without government interference. The right to free speech includes protests and distasteful speech that one might find offensive or racist.

But, the First Amendment as written applies only to actions by Congress, and by extension the federal government. Over time, it’s also come to apply to state and local governments. It’s basically a restriction on how the government can limit citizens’ speech.

The First Amendment does not, however, apply to nongovernment entities. So private companies – professional sports organizations or theater companies, for instance – can actually restrict speech without violating the First Amendment, because in most cases, it doesn’t apply to them (unless the restriction is illegal for other reasons). This is why the NFL could ban DeAngelo Williams from wearing pink during a game in honor of his mother, who had died from breast cancer, and fine him thousands of dollars when he later defied the rules and did it anyway.

DeAngelo Williams is outspoken in supporting breast cancer research. The NFL can limit when he can display his position.

AP Photo/Nell Redmond

How does all of this affect celebrities? In a nutshell, if a celebrity is an employee of, or has some kind of contract with, a nongovernment entity, his speech actually can be restricted in many ways. Remember, it’s not against the law for a nongovernment employer to limit what employees can say in many cases. While there are other more limited protections based on state and federal law that protect employee speech, they are incomplete and probably wouldn’t apply to most celebrity speech. Any questions about what a public figure can or cannot express, therefore, will start with the language of any contracts she has signed – not the First Amendment.

![]() For better or worse, celebrities can make significant impacts on policy, politics and culture, and have been doing so for centuries. But speaking out can put them at risk. Celebrities can be fined by their employers, like DeAngelo Williams, have their careers derailed, like the Dixie Chicks, or receive death threats, like Colin Kaepernick. Even so, their involvement can provide an influential platform in promoting and creating societal change.

For better or worse, celebrities can make significant impacts on policy, politics and culture, and have been doing so for centuries. But speaking out can put them at risk. Celebrities can be fined by their employers, like DeAngelo Williams, have their careers derailed, like the Dixie Chicks, or receive death threats, like Colin Kaepernick. Even so, their involvement can provide an influential platform in promoting and creating societal change.

Shontavia Johnson, Professor of Intellectual Property Law, Drake University

Shares