Cézanne is credited with the invention of modern art. Or rather, he should be. My colleague at the Guardian, Jonathan Jones, recently published a column arguing as much. That while the textbooks tend to point to Picasso, and particularly his 1907 "Les Demoiselles d’Avignon," as the first work of Modernism, a shift in artistic style brought about by the interest of artists in the art and craft of non-European regions (Africa, Oceania, Asia), Cézanne was engaged in much of the same innovation without ever leaving his native Provence.

Cézanne’s leap forward was seen by traditionalists as a fold backward: He flattened the three-dimensionality that, for centuries, artists had striven for; the goal of art was to achieve the naturalistic illusion that a flat canvas painting is actually a view into a three-dimensional reality. Cézanne took this three-dimensional reality and folded it, like undoing an intricate work of origami. He intentionally removed the illusion of depth and played with dimensionality, messed with our minds by toying with angles and foreshortening: One apple might be correctly painted to be seen from one angle, but the pear next to it is illustrated as if seen from a different angle entirely, thus the two should not exist in the same painting. He also, as Jones notes, broke down faces into masks, into blocks of color that resemble sculptures. This is most obvious with Picasso and Braque’s Cubism, but they both cited Cézanne as their inspiration. Jones’ article points out how odd it is that art history books defy the admission of Picasso and Braque, who tried to credit Cézanne with this “invention” of Modernism, while the historians like to credit Picasso and Braque.

Which brings me to what might be the greatest children’s book ever written and illustrated, "Goodnight Moon" by Margaret Wise Brown, with pictures by Clement Hurd.

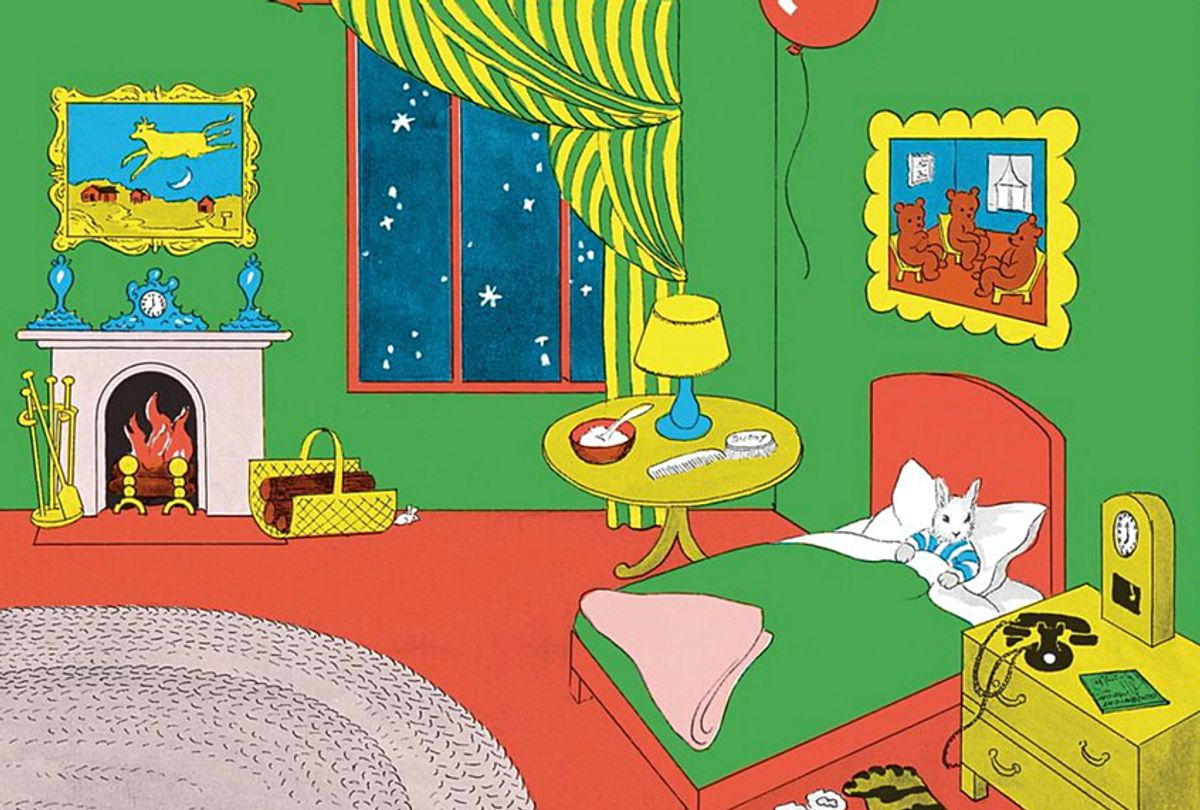

This slim picture book, published first in 1947 for the youngest of children, is a super-minimalist text in which a bunny mother helps her bunny baby to sleep by saying “Goodnight” to a variety of objects around baby bunny’s bedroom: "Goodnight room. Goodnight moon. Goodnight cow jumping over the moon. Goodnight light and the red balloon. Goodnight bears. Goodnight chairs." And so forth.

I’m writing this article on a transatlantic flight to my latest book tour, and I do not have a copy of "Goodnight Moon" with me. I don’t need it. I’ve memorized it, each word and each picture. It’s been a balsam for both my daughters. If they are fussy, I begin reciting the words to this story, and they immediately calm. (For some reason, singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” used to also work for my elder daughter, but this story is guaranteed for both.) I sometimes felt like the Monty Python sketch about the world’s deadliest joke, in which a British soldier runs through the forest, surrounded by Nazi opponents, with no weapon but reading a German translation of the joke aloud, a joke so potent that it strikes down the enemy into fits of deadly laughter as he runs past them, reciting. So it was on some occasions, when my babies had trouble sleeping and cried. As I carried them in my arms, I begin reciting the words to "Goodnight Moon," and calm followed.

The illustrations are deceptively simple-looking. We see a room, angles askew, as if the artist isn’t very good at depth (though of course this manipulation is intentional). We see objects in the room, simply drawn, the colors in bright blocks, with almost no shading. Ingeniously, as the bunny gets sleepier, the room gets darker. A fire in the hearth, beside the sitting bunny mommy, grows dimmer, the light outside fades, until the bunny is asleep and the room is completely night-dark. But before that darkness, there’s this postmodern twist. The gem-colored bedroom scenes, which have alternated with black-and-white (rather, pen and ink) austere pages, now yield to a page with nothing at all on it. “Goodnight nobody.” Then there is a false ending worthy of a Beethoven symphony. We expect the story to end with “Goodnight to the old lady whispering hush.” But it does not. It’s a false ending, and instead it goes on, floating us outside the window, beyond the warm, cozy bedroom, into the air and stars outside, flying heavenward.

Curious about this superpowered text, I asked some child specialists. Dr. Carla Horwitz, who recently retired from running the award-winning progressive preschool Calvin Hill, in New Haven, Conn. (of which I’m a graduate), told me, “The book is so simple that you know there must have been an extraordinary amount of work to make it as elegant and simple as it is. The book has soothed many a child, and many an adult, as well.”

She continues: “I think there are many elements that make this literature that appeals on many, many levels. First of all, the rhymes and the rhythm. Then the fact that everything is a known element, close to the child, in fact in the child’s room, so that everything named is an old friend. Going to bed is a time fraught with much stress. Saying ‘goodnight’ is really a separation, and since children have so little experience, they don’t know that it’s brief, and that the daylight and the people they love will return. Surrendering to sleep is nearly the ultimate separation (other than death). And babies don’t have a theory about reunion and the temporal understanding to realize the sleep time is brief. It might be forever! And it’s in the dark, though this book actually gets dimmer and dimmer, but never pitch black. And you’ll note that, when the bunny finally does fall asleep, the old lady’s chair is finally empty. I never thought of her as the mother, more like a grandma or a nanny perhaps. But obviously she can be whatever and whomever you want.”

It was written in the year Carla, and her husband, Bob, a psychologist, were born. As Bob told me, “I wonder if it might have been read to us when we were little — we don't really recall. We remember it mostly as a favorite of our little girls, who are now 30-somethings, and I imagine they'll read it to their kids, too, as you are doing with yours.”

He also notes some inside jokes hidden in the images, such as another book by the same author and illustrator, "Runaway Bunny," which appears on a shelf in this baby bunny’s bedroom.

Bob continues, “What a loaded term that word ‘goodnight’ is. We say it to each other, as if we know that not all nights actually are good, and as if wishing would make it so. Kids are quite naturally afraid of the dark (so, too, are many adults), and not without reason: At the very least, it's hard to see where you're going, and easy to bump into things, but in some deeper way, it does bring up fears that the sun will never shine again, and that this night may be the beginning of the end. So how comforting it is to have someone saying ‘goodnight,’ over and over, acknowledging the presence of all that's in the room, still there tonight, as it was last night, still there tomorrow. And how comforting still to say goodnight to noise, as the book ends, and fall quietly asleep.”

I asked for thoughts from my own father, Dr. James Charney, who read this to me and had it read to him, and has now read it to his granddaughters. He is a child psychiatrist, and entirely aware of the power of soothing words and images, which actually give the slowly sleeping child a sense of control that bedtime otherwise lacks. “To me,” he said, “what makes it so haunting is the incantatory quality of the ‘goodnights.’ The book is made to be read again and again to your child, and if you allow it to, it can put a spell on parents, too. You find yourself saying each ‘goodnight’ with a quiet and quieter sing-song rhythm, which just naturally leads to ‘hush.’ The Clement Hurd drawings brilliantly mirror this: The objects in the room become more and more grey, the shading of each picture becomes faded, but never quite dark — nothing is scary but everything changes. Just like night should be. And the child enters that often difficult stage of sleepiness, not needing to fight it, because he is in control. He is saying ‘goodnight,’ in charge of the farewell for another day (or night), confident that all will be there for him to say ‘hello’ to in the morning.”

This month, Cézanne’s Portraits opens at London’s National Portrait Gallery, and this also marks the 70th anniversary of the publication of "Goodnight Moon." Clement Hurd’s illustrations feature the same collapsing of the illusion of depth that Cézanne initiated in his paintings of the late 1890s. The brilliance of these illustrations comes as less of a surprise when we learn that Hurd studied art with modernist legend Fernand Léger. But Modernist poetry is also an influence to this book, the stripping away of all that is not needed, even some punctuation, and the repetition of key words. This little book, which of course can be enjoyed without this sort of deconstructionist analysis, by those with tiny fingers and soft-closing eyelids, is a truly great work of Modernist art, its text as powerful an incantation of Modernist poetry as I know, and its illustrations richly in line with the tradition launched by Cézanne.

Shares