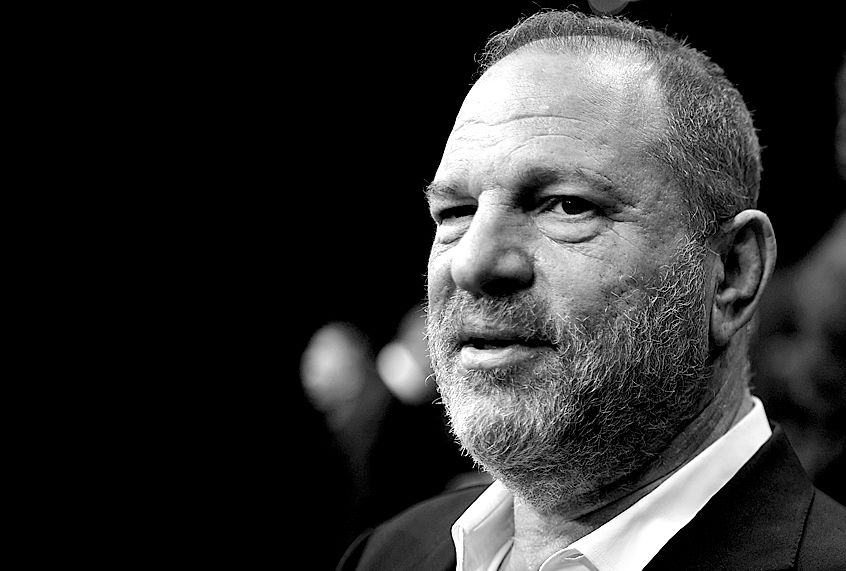

One theme keeps emerging from the Harvey Weinstein story: If you’re a rich and powerful man, no amount of evidence suggesting you’ve committed a sex crime is ever “enough.”

After Italian model Ambra Battilana recording a damning conversation with Weinstein at New York’s TriBeCa Grand Hotel, New York Police Department officers believed that had admitted to enough criminal activity on tape to justify arresting on a misdemeanor charge him, according to The New York Times. On the previous day, Battiliana had reported to police that Weinstein had groped her breasts and stuck his hand up her skirt during a business meeting. As she talked to him outside of his hotel room, he twice confirmed that those events had happened.

“Oh, please, I’m sorry, just come on in,” Weinstein said on the tape. “I’m used to that. Come on. Please.”

When Battilana replied “you’re used to that?”, Weinstein confirmed “Yes. I won’t do it again.”

As the conversation became increasingly testy, a police officer concerned for Battilana’s welfare posed as a TMZ reporter to put an end to the conversation. Later, another law enforcement officer approached Weinstein and identified himself accordingly.

Weinstein quickly fought back against Battilana’s accusation, hiring researchers to uncover that she had made a sexual assault complaint in Italy that was dropped after she changed her account of what happened. Because of this background, prosecutors claimed that they didn’t feel that Battilana would be believed as an accuser.

They were also concerned that Weinstein could attribute his touching her breasts to his desire to determine if she had received augmentation. This, they felt, was potentially excusable given that they were meeting about advancing her modeling career.

As defense lawyer and former Manhattan prosecutor Mark Bederow told the Times “The idea that Weinstein’s criminal intent was unprovable because of his stated ‘professional need’ to personally inspect her breasts doesn’t pass the laugh test.” Indeed it does not. And, yet, it either informed the D.A.’s decision or offered his office what it thought was a handy excuse not to prosecute.

It should be noted that D.A. Cyrus Vance Jr. is now under scrutiny given reports that he received a considerable financial donation to his campaign from a lawyer associated with Weinstein shortly after the office chose not to prosecute Weinstein. He’s also being criticized for a similar situation related to his handling of a potential fraud case against Ivanka Trump and Jared Kusher. Vance is now running for the office again, unopposed.

One source also claimed that Weinstein planted disparaging stories about Battilana in tabloids in order to undermine her public credibility.

Nevertheless, one senior police official told the Times, “We brought them a very good case. He admitted, twice, doing it. That’s probable cause to make an arrest” for third-degree sexual abuse, a misdemeanor which could have landed Weinstein in jail for up to three months if he had been convicted.

Prosecutors insisted that the audio recording was insufficient because, although Battilana had gotten Weinstein to admit to touching her breasts, the conversation was stopped before he also acknowledged reaching under her skirt. One police official insisted that prosecutors were kept informed about the case the entire time.

The prosecutors’ reluctance to pursue Weinstein is reminiscent of a similar story which came out this month. As NBC’s Ronan Farrow accumulated more and more evidence of Weinstein’s alleged abuses, the network continued to refuse to publish the story, claiming that he did not have enough evidence. In a somewhat contradictory vein, however, they also claimed that Farrow should stop investigating the story altogether. Farrow eventually published his story in “The New Yorker.”