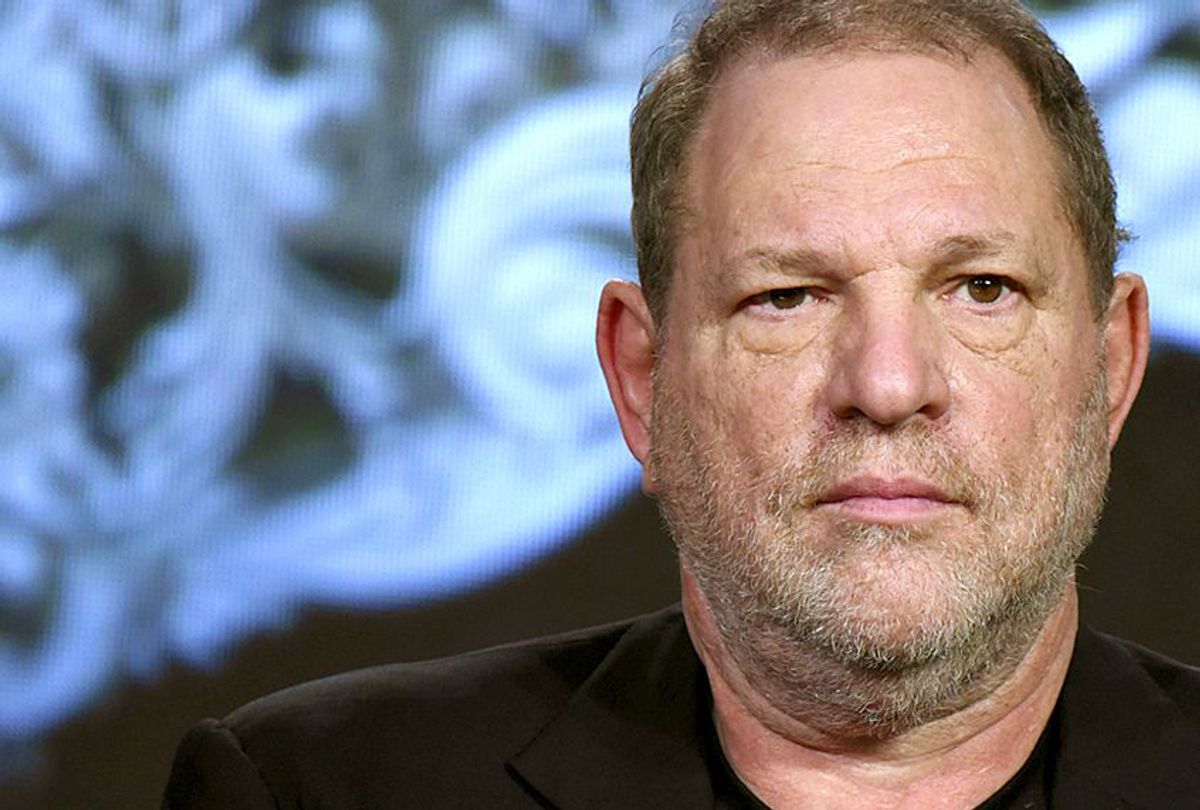

After both The New York Times and The New Yorker published lengthy exposés of movie mogul Harvey Weinstein's long history of alleged sexual harassment or assault -- against pretty much any young woman who felt dependent on him for job opportunities -- a larger question has emerged: What can be done? Not about Weinstein in particular, as it seems that the film industry is ready to eject him from a position of power and influence. (As it largely did not do in the cases of Woody Allen and Roman Polanski.) But Weinstein is just one part of a much larger problem, which is so widespread and seemingly intractable that society needs more than Twitter hashtags to address it.

The solutions will be multifaceted and complicated, of course, but one important piece of the puzzle is the role of unions. Work-related sexual harassment of the sort Weinstein is accused of dishing out is, ultimately, a labor issue. The particulars of the issue can vary wildly from industry to industry, and unions are in a unique position to help tailor systemic responses to the specific conditions of their members' work environments.

Many, probably most, of Weinstein's accusers would be represented by SAG-AFTRA, the principal union for film and television actors. That union responded to the allegations by releasing a statement calling the alleged behavior "abhorrent and unacceptable" and adding that such behavior is "more prevalent than our industry acknowledges and many times victims are afraid to tell anyone." They recommended that people who have issues with sexual harassment call their hotline.

Salon reached out repeatedly to SAG-AFTRA to see if it had plans to address this issue further. The organization responded by sending a link to its public statement.

There's a relatively recent precedent, however, for the questions that Hollywood-based unions are clearly facing regarding their role in fighting sexual harassment. The more New York-centric world of theater went through a similar, if much smaller, controversy two years ago, and there's much to be learned from how the industry, and Actors' Equity in particular, dealt with the issue.

In March 2015, Patrick Healy of The New York Times reported on the theater world's massive sexual harassment and violence problem. Theater, like Hollywood, is a highly decentralized business, where the lines between work life and social life are often blurry, presenting unique challenges. Pressure was mounting on Actors' Equity to take action.

“These issues are ultimately the responsibility of the employer, and the union’s role is to help facilitate getting the employer to take the appropriate actions," explained Barbara Davis, the COO of the Actors' Fund, a service organization that helps creative professionals navigate the problems of working in fields where employment is often insecure and erratic.

Actors' Equity reached out to the Actors' Fund during the mounting controversy over sexual harassment for help. The fund developed a program to train Equity business representatives, theater staff and others on how to spot sexual harassment problems and how to take reports and channel them correctly when such problems arise. Davis explained that the fund has a full staff of social workers who can speak with complete confidentiality to anyone who is having workplace issues — and if they need a lawyer, the Fund will refer them to one.

(Davis emphasized that these confidential counseling and referral services are available to anyone who works in the entertainment industry, not just actors or union members.)

The training seminar strategy has its critics, who argue that these are mostly ass-covering measures from companies trying to avoid liability and are ineffective at actually stopping harassment. Research compiled by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission largely concurs. Programs that are tailored to specific work environments, however, and that target and empower middle managers to deal with the problem, have been shown to work.

That was the strategy the Actors' Fund took when Equity asked for help. Business representatives and stage managers really didn't know what to do when allegations of sexual harassment came up, and the training programs offered answers. Davis emphasized that the program also addressed "what is unique about the industry and how to understand sexual harassment within that context."

One problem, a friend of mine who is an actor told me, is that "our social lives and our work lives are so intermixed," which can "make it easier for [abusers] to get away with it."

"It also does provide challenges and questions for theater companies and unions, because they are responsible for what happens on the job," he added, "and it's a lot less clear in this world what is really on or off the job."

In addition to this, Davis noted that the theater is an industry that can involve "nudity and intimacy on stage, creative exercises, tight quarters, traveling together, all those kinds of things," which can offer abusers an opportunity to pretend their harassment was simply flirting or normal social behavior.

But those circumstances, she made clear, don't change "what sexual harassment is or is not."

Weinstein's reported behavior, for instance, often appears to meet the definition of "quid pro quo harassment," meaning a situation where a target is made to feel that her job opportunities depend on providing sexual favors to powerful people. That it happened in hotel rooms and apartments rather than an office building doesn't change this.

Another problem for the industry, Davis explained, is that workers rarely have "have one long-term employer," but instead "go from job to job and work with different employers." The fear is that speaking out will stain your reputation, making other jobs hard to get.

"Hollywood is built on relationships and the way you keep relationships is by playing nice," Nell Scovell of The Washington Post wrote last week. "If I bust my assaulter, somehow that makes me the troublemaker. Suddenly, I’m the jerk." She suggested that lawyers and agents could do more to circulate the names of toxic people in their industry, to protect the people they represent.

Davis said that while the Actors' Fund's program with Actors' Equity is only a year-and-a-half old, it's been successful enough that small employers, such as theater companies, have already requested seminars, while other entertainment industry unions have explored the possibility of hosting programs of their own.

Lowell Peterson, executive director of the Writers Guild of America, East, emailed a statement to Salon saying that, in light of the Weinstein accusations, they are "looking at the tools" such as "the grievance process and labor-management committees" and asking members for input on how to improve those things and be more proactive about preventing, reporting and stopping harassment.

To be clear, no one should expect unions, or worker representatives generally, to single-handedly end this problem in the entertainment industry (or anywhere else). Sexual harassment is the result of a larger culture and everyone needs to play a part in changing that. But unions have a special role to play. They have the insider knowledge to craft nuanced responses and are often the only centralized organization in their industry that can come up with standardized protocols for confronting this problem. They can create forums for people to discuss these issues and empower industries to change their cultural atmosphere.

Most importantly, fighting for workers' rights is what unions are for. As we confront the legacy of the Weinstein revelations, we can hope to see more entertainment unions step up and find more robust ways to address this chronic problem.

Shares