As NFL protests continue to be debated, both in and out of the league, the legacy of sports activism has by nature, also taken center stage. It's a history that, in balance, disproves the often-stated belief that players should just stick to their day jobs, that politics have no place on our fields or courts.

For every brave and iconic Muhammad Ali story, there are scores of less well-known athletes using whatever platform they have to push forward social-justice causes that mean the most to them. Though rarely heard, their stories are often as essential.

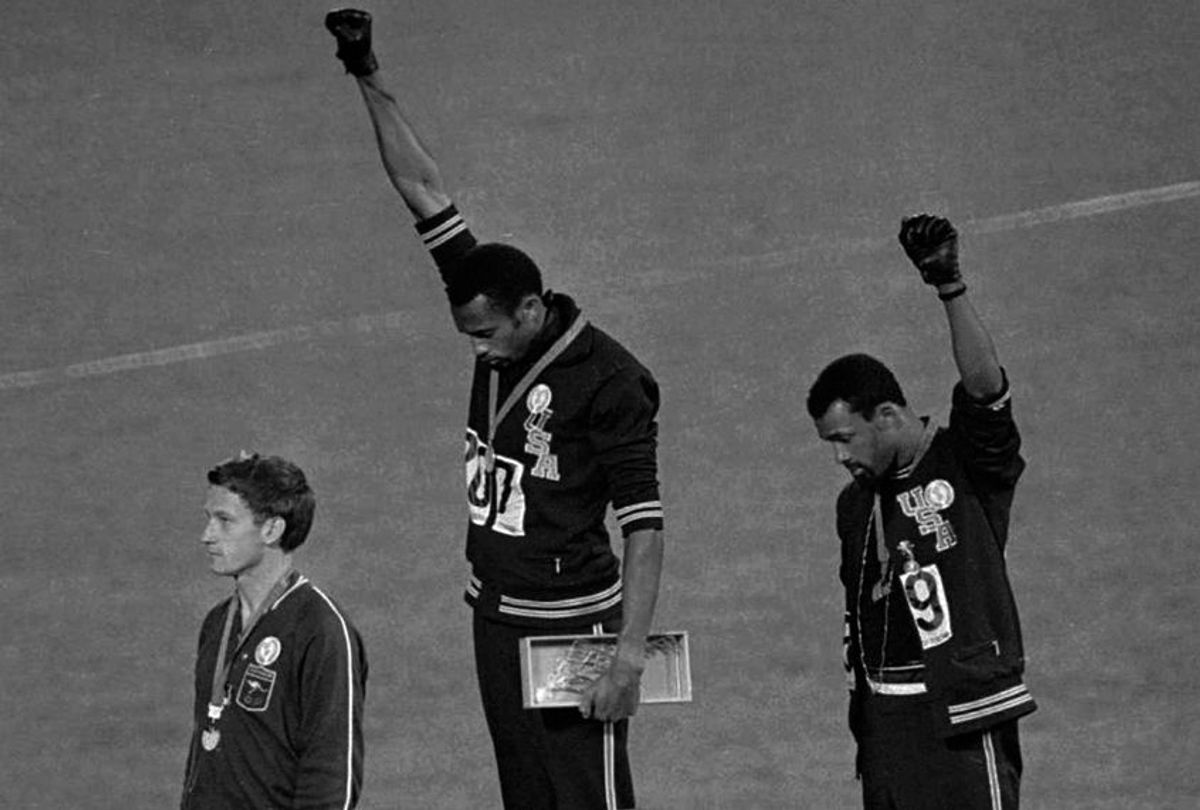

One of those stories, is the tale of the white man, Australian runner Peter Norman, who won silver at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City and stood on the podium as Americans John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised their black-gloved fists in the air in support of African-American rights and dignity.

For many, Norman was seen as simply a bystander, or "the white guy" in the photo. A largely insignificant figure in one of the Olympics' most iconic moments. But as Smith and Carlos held their fists up high to highlight the racism and segregation that marked life as a black person in America, Norman stood in quiet solidarity. Hard to see in the photo is a small badge he wore that read: "Olympic Project for Human Rights," an American organization started the year before to protest global racial injustice. After all, he was coming from Australia, which sports writer Dave Zirin describes as "a country that at the time held racial exclusion laws that rivaled apartheid South Africa."

"I’ll stand with you," Italian writer Riccardo Gazzaniga said John Carlos remembers. "I expected to see fear in Norman’s eyes, but instead we saw love."

While the narrative around the emblematic photo has often left out Norman, Australia certainly did not forget his actions. Four years later and in 1972, Norman was not part of his country's Olympic sprinter team in Munich, "despite having run qualifying times for the 200 meters thirteen times and the 100 meters five times," Gazzaniga said.

Norman's career in competitive athletics was over, even though he was so fast that he still holds Australia's national record. He was ostracized, with work largely impossible to find. "If we were getting beat up," Zirin said that John Carlos remembers, "Peter was facing an entire country and suffering alone."

Australia offered Norman many chances for redemption. Publicly condemn Smith and Carlos' actions and he would be embraced for the athletic trailblazer he was. More importantly, it was "A pardon that would have allowed him to find a stable job through the Australian Olympic Committee and be part of the organization of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games," Gazzaniga wrote. Norman refused.

In 2006, Norman died from a heart attack. Tommie Smith and John Carlos, among other friends, were his pallbearers. Six years later, the Australian House of Parliament issued an official state apology to Norman:

That this House; Recognises the extraordinary athletic achievements of the late Peter Norman, who won the silver medal in the 200 metres sprint running at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, in a time of 20.06 seconds, which still stands as the Australian record;

Acknowledges the bravery of Peter Norman in donning an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge on the podium, in solidarity with African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who gave the black power salute;

Apologises to Peter Norman for the wrong done by Australia in failing to send him to the 1972 Munich Olympics, despite repeatedly qualifying; and Belatedly recognises the powerful role that Peter Norman played in furthering racial equality.

After the news, John Carlos told The Nation, "There is no one in the nation of Australia that should be honored, recognized and appreciated more than Peter Norman. He should be recognized for his humanitarian concerns, his character, his strength and his willingness to be a sacrificial lamb for justice."

Tragically, it is an honor and rectification that Peter Norman never got to experience. Similarly, it took the United States 40 years before it nationally recognized John Carlos and Tommie Smith for the American heroes they are, when they were presented with the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the ESPYs in 2008.

As Colin Kaepernick endures unemployment, it's as clear today as it was in 1968 that engaging in sports activism can be a long and often lonely road. The risk is great and yet, the effects are so short-lived. Let's hope it doesn't take 40 years for the U.S. to celebrate Kaepernick.

Shares